By Leslie Clark Lewis, Class of 2009

Perhaps it was the publicity drumbeat for the Auditorium Building that first drew the good burghers and businessmen of the far west to the architectural firm of Adler & Sullivan. Whatever the reasons, by 1890 the firm had in hand four commissions for commercial structures in three western cities: the Pueblo Grand Opera House in Pueblo, Colorado; the Seattle Opera House in Seattle, Washington; and the Dooly Block and the Hotel Ontario, both in Salt Lake City, Utah. With these projects and the Wainwright in St. Louis on the drawing boards, Adler & Sullivan were set to make a name for themselves outside of Chicago.

Promising Beginnings

With a population of less than 25,000, Pueblo, Colorado in 1888 would have seemed an unlikely location for an opera house. But it was a small city with big ambitions. Mining, railroads, and steel-making had helped make Pueblo prosperous. Surely an elegant theater would help achieve its aim of being a major cultural player in Colorado.

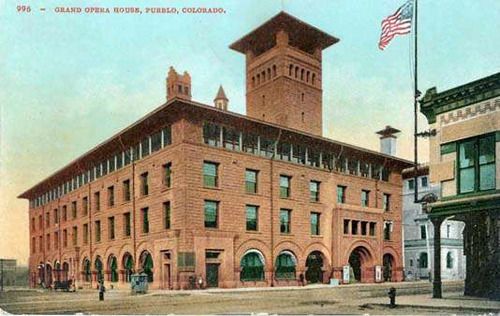

The agreement hiring Adler & Sullivan for the $400,000 Pueblo Grand Opera House was finalized on June 12, 1888. Three weeks later, Dankmar Adler visited Pueblo, bringing with him Louis Sullivan’s preliminary sketches for the building. In addition to the theater, retail shops and offices were planned for the project. Final plans were signed off on in January 1889. After delays attributed to problems with the foundation, construction began in earnest in January of 1890, and the building was complete in October.

Pueblo residents marveled at the building, which took up nearly the entire block. The exterior was clad in rusticated Manitou red stone on an eight-foot base of gray granite. Modeled after the Auditorium Building, the Opera House had a 131-foot tower with observation platform and, as an added bonus, a rooftop garden.

In his book Louis Sullivan, his Life and Work, Sullivan biographer Robert Twombly praised the auditorium “as one of Adler & Sullivan’s more imaginative.” Their previous experience with the Auditorium Theater, McVicker’s Theater and the Grand Opera House in Chicago served them well in Pueblo. The acoustics were superb, the sightlines unobstructed, and stage mechanicals were cutting-edge. The auditorium boasted 1100 seats and, “The rear gallery was the first in America not supported by columns.” Inside the auditorium, theater-goers were amazed by the gold-leafed proscenium arch, floral and geometric detailing, and the 500 electric lights worked into the ornamentation. Only Louis Sullivan could have designed such an interior.

The first booking in the Pueblo Grand Opera House was the Duff Opera Company of Chicago, opening with a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe. Pueblo was on its way.

Meanwhile, in Salt Lake City, another Adler & Sullivan project was taking shape. Businessman John F. Dooly, who had made his fortune in livestock and real estate, proposed an office building in a bustling area of the city. Utah was not yet a state, but Salt Lake was booming, with a population of more than 100,000. J.F. saw a golden opportunity and selected Adler & Sullivan to make it happen.

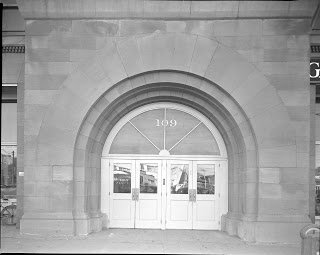

The $300,000 Dooly Block plans were approved in October of 1890 and construction began early the next year. The building was a big deal in Salt Lake City. The Salt Lake Tribune reported regularly on construction progress, eagerly noting when the stone columns were complete or the boiler was installed. “The building is the most pretentious in the Territory, and will cost $250,000 when ready for occupancy,” crowed the Tribune. First tenants would include a bank, several attorneys, and the newly-formed Alta Club, an exclusive private men’s club initially open to non-Mormons only!

The finished building was seven stories tall and used post, lintel, and arch construction. Twombly noted that it was the last of Sullivan’s major Richardsonian buildings. It had large windows for retail on the first floor, with paired windows on the next five floors ending in an arch at the top. Mechanicals were in the attic, behind small windows. The roof was flat with an overhang, similar to the Wainwright, which Sullivan was designing at the same time.

Twombly wrote that “Sullivan successfully transformed the arch, a Romanesque symbol of muscular compression, into an altogether different image of upward thrust, actually a rather Gothic objective. Thus, it was that the Dooly Block was also a continuation, the final link in the preskyscraper chain, of his search for a way to create a ‘system of vertical construction’… it anticipated Sullivan’s next, most significant phase of development.” That may not have been how the people of Salt Lake understood it, but the building received rave reviews for its beauty and luxury both inside and out.

Disappointments

Two of the four western projects did not see the light of day. And wouldn’t you know, it was all about the money.

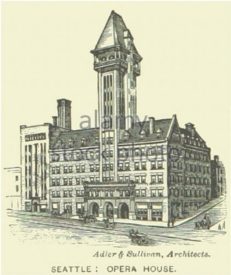

In June of 1889, Seattle, Washington suffered its own devastating fire, which destroyed most of its downtown. Much like Chicago, the city was forced into a massive rebuilding campaign. As part of the recovery, local investors sought a project that would project “a symbol of metropolitan achievement” – an opera house. The $325,000 structure would contain the Seattle Opera House auditorium, a hotel, restaurant and shops. Adler & Sullivan were awarded the commission.

Planning began in the summer of 1890. The contract was signed, the final plans were completed in September, and Adler & Sullivan sent their representative to oversee the project. But all was not well in Seattle. At least three different stock companies had been formed in succession to finance the project; none of them succeeded in securing enough money. Just before excavation was to begin, Adler & Sullivan were highly displeased to learn from the backers that there was not enough money to move forward.

In 1890, anticipation in Salt Lake City was high for the planned $300,000 Hotel Ontario, which was to sit next to the Dooly Block. The Salt Lake Tribune boasted, “The better part of three-quarters of a million of dollars will be expended before the hotel will be ready for occupancy, and suffice it to say that it will be the most elegant, costly and finest equipped hotel plant between Chicago and the Pacific Coast.”

Unfortunately, the hotel would be the second major disappointment for the firm that year. The contracts were signed in November and excavation had begun. Twombly noted that Frank Lloyd Wright said the foundation had actually been completed. Whatever the case, construction was halted shortly thereafter because the financing had fallen through, and the project as planned was abandoned.

Bitter Ends

The two completed Adler & Sullivan buildings in the west were not destined for long lives. Each fell victim to a common enemy of their time.

The Pueblo Grand Opera House delighted the community for only 32 years. Unfortunately, the block burned to the ground in a huge fire in the early morning hours of March 1, 1922. The fire started on the top floor and quickly spread to adjacent spaces. Although the fire department was called almost immediately, frigid weather impeded the work of the firemen. It was reported that the temperature was 22 degrees below zero, with strong winds fanning the flames. Nothing could be saved, and the Pueblo Opera House is now only a dim memory.

The fate of the Dooly Block was even more tragic because the building might have been saved. By the early 1960s, the neighborhood around The Dooly had changed. Many businesses had moved to newer buildings or other parts of the city, and the area was becoming, in the eyes of some, unsightly. Older buildings were being demolished in favor of parking lots. The Dooly met this fate – but not without a fight.

When he learned of the planned demolition of the Dooly Block, Chicago’s Richard Nickel tried heroically to save it. He visited Salt Lake and petitioned Mayor J. Bracken Lee, writing, “How many buildings of equal architectural merit do you have in Salt Lake City? Instead of being proud of this building, you ignore it. Instead of offering tax relief to the owner, or cleaning the neighborhood up, the city government is silent”. In 1965, despite Nickel’s efforts, the building came down anyway. Fortunately, he photographed the Dooly Block while it was still standing.

Utah blogger Jonathan Kland wrote that there was an upside to this episode. “Longtime Utah preservationists consider it the Salt Lake equivalent of Penn Station – the loss laying the groundwork for the preservation movement in Utah.” It was a lesson learned too late not only in Salt Lake City, but in Chicago as well.

Adler & Sullivan went on to design structures seen by many more people than ever viewed their western buildings. Today, the Pueblo Grand Opera House and the Dooley Block are almost forgotten, but they helped set the stage for the architects’ future success.

Primary sources:

Louis Sullivan, His Life & Work by Robert Twombly

Louis Sullivan, Prophet of Modern Architecture by Hugh Morrison

Salt Lake Architecture blog by Jonathan Kland

Pueblo Firefighters Historical Society

Pueblo’s Grand Opera House, a history, PULP newsmagazine

Leslie,

What a wonderful summary about buildings that I, at least, knew nothing about. This is an excellent summary of both architecture and business practices of the late 19th century. Thanks so much,

Ellen