By Maurice Champagne, Docent Class of 2004

Of the six “principal elements” that Daniel Burnham laid out at the end of the Plan of Chicago, “[t]he creation of a system of highways outside of the city” is the least noticed. Chapter III, titled “The Metropolis of the Middle West”, identifies Chicago as the metropolis of what was once called the Northwest Territories. Burnham states, “The domain over which Chicago holds primacy is larger than Austria-Hungary, or Germany or France.” (1) In this chapter, Burnham devotes five pages arguing for new and improved roadways to connect nearby towns (now suburbs) to each other as well as to Chicago. He starts by proposing a “highway should be built from Wilmette along the western shore of Lake Michigan to Milwaukee.” (2)

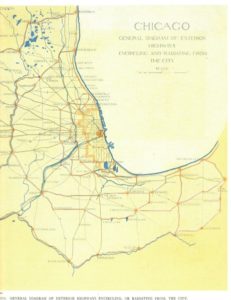

Some say that Burnham did not anticipate the impact of the auto. However, one look at Plate XL should dispel that misconception; he even wrote: “all roads lead to Chicago.” (3)

Burnham advocated that roads connect the suburban towns to each other follow this formula: “If we take arbitrarily a radius of sixty miles from the heart of Chicago… the distance from the center to circumference is no greater than… the automobilist may cover in two hours.” (4)

And automobiles were in the news! In 1903, Horatio Nelson Jackson, a physician with no driving experience, drove from San Francisco to NYC on a $50 bet. (5) He was accompanied by Sewall Crocker as his mechanic and a bulldog wearing goggles. The event was so famous that it was reported by newspapers across the country, including the Chicago Tribune on Oct. 6, 2003, so we can assume that Daniel Burnham knew about it. The first Ford auto dealership outside of Detroit opened at 1444 S. Michigan Avenue in 1905. (6) By 1906, the U.S. had almost 106,000 auto registrations, and state registrations nearly tripled to almost 306,000 by 1909. (7 & 8) Eight auto manufacturers produced over 75,000 new cars in 1909. (9)

Burnham envisioned four outer ring-roads – (10) an “interurban highway system” using the “ninety-five per cent of the necessary road now exist[ing]” (11) connecting Kenosha WI to DeKalb, Morris and Kankakee to Gary or Hobart IN. He wrote that an additional 5% of roadway needed to be built to complete it. (12) Of course, in 1909 those roads would have been 2-lane highways, which now are identified as U.S. highways or state roads with numbers. We were familiar with this system before the expressways and interstate highways were built.

Realization: “Highways encircling and connecting the region were constructed in the 1920s, coordinated by the Chicago Regional Planning Association.” (13) The outermost route Burnham proposed was from Kenosha WI through DeKalb, Morris and Kankakee to Gary and Hobart IN. Confidently, Burnham wrote, “From Kenosha on the north, around to De Kalb on the west and thence to Michigan City on the south, all roads lead to Chicago.” (14)

Roads we know today as county roads, Illinois highways and U.S. highways can be used to follow the four “ring roads” that Burnham envisioned. “The rapidly increasing use of the automobile promises to carry on the good work begun by the bicycle… in promoting good roads and reviving the roadside inn…” (15) But our interstates (I-90/94, I-294, I-290, I-355, I-88, I-80) connect surrounding towns and villages, just exactly as Burnham included in the 1909 Plan. In a sense, the north part of I-90/94 from 15 miles west of Kenosha connects to I-294, then into I-80, just 10 miles south of Gary. Together they create the outer ring road that Burnham wanted. These interstates take us from near Kenosha through the western suburbs to Gary and Michigan City.

Our expressways create Burnham’s “interurban highway system” but one with massively larger roadways than he would have conceived. Yet he was aware that his plans would be modified when finally implemented. “Therefore, it is quite possible that when particular portions of the plan shall be taken up for execution, wider knowledge, longer experience, or a change in local conditions may suggest a better solution.” Today some might wonder if the expressways are a “better solution” (16) to connect suburban towns to each other and to Chicago, or if they just by-pass the places Burnham hoped to connect.

To read Part 1, CLICK HERE. To read Part 2, CLICK HERE. To read Part 3, CLICK HERE.

Sources:

[1] Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago, Commercial Club of Chicago, 2008, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1993, p. 47

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 38.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 32.

[1] Plan of Chicago, pp. 36-37.

[1] https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/horatios-drive

[1] http://chicago-architecture-jyoti.blogspot.com/2009/09/motor-row-district.html

[1] http://chicago-architecture-jyoti.blogspot.com/2009/09/motor-row-district.html

[1] https://allcountries.org/uscensus/1027_motor_vehicle_registrations.html

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Automobile_Production_Figures

[1] Plan of Chicago, pp. 39-41.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 122.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 122.

[1] The Plan of Chicago: A Regional Legacy, Copyright 2008, Chicago Metropolis 2020, p. 2

http://burnhamplan100.lib.uchicago.edu/files/content/documents/Plan_of_Chicago_booklet.pdf

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 47.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 42.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 2.