By Jen Masengarb, former CAF Director of Interpretation and Research

This article was originally published in the Fall 2015 issue of Docent Quarterly

“Architects don’t like to talk about style. Ask an architect what style he works in and you are likely

to be met with a pained expression or with silence.” – Witold Rybczynski in The Look of Architecture

The term “Chicago School” is everywhere – from the dozens of Chicago guidebooks we sell in the shop to lengthy Wikipedia entries. It’s a term deeply tied to CAF’s history and early mission. In 1966, a small group of architects and preservationists banded together to save H.H. Richardson’s Glessner House, forming “The Foundation for the Chicago School of Architecture, Inc.” By 1988, the name was amended to what we now know today. The Chicago school narrative heavily influenced those who were taught to interpret skyscrapers in the last decades of the 20th century.

But the use of the term has been widely challenged, especially in the past 15 years. Even Wikipedia authors have addressed the issue:

While the term “Chicago School” is widely used to describe the buildings constructed during the city in the 1880s and 1890s, this term has been disputed by scholars, in particular in reaction to Carl Condit’s 1952 book The Chicago School of Architecture. Historians such as H. Allen Brooks, Winston Weisman and Daniel Bluestone have pointed out that the phrase suggests a unified set of aesthetic or conceptual precepts when, in fact, Chicago buildings of the era displayed a wide variety of styles and techniques. Contemporary publications used the phrase “Commercial Style” to describe the innovative tall buildings of the era rather than proposing any sort of unified “school.”

Many of you will remember Professor Robert Bruegmann’s March 2012 Continuing Education lecture on his seminal essay “The Myth of the Chicago School.” Docents came a way with a new understanding of the era and some of the challenges in the continued use of the term today.

At CAF, our understanding is changing, too. In recent years docents have read Daniel Bluestone’s essay “Preservation and Renewal in Post-World War II Chicago.” In that work. Bluestone outlines how preservationists first used the term in their arguments. Additional lectures and readings from Joanna Merwood-Salisbury (Chicago 1890 – The Skyscraper and the Modern City, 2009) and Thomas Leslie (Chicago Skyscrapers 1871-1934, 2013) have broadened the ways in which we learn about and meant to the people who designed and built them, worked inside their walls, and gazed up at their facades. Leslie’s groundbreaking research into the materials, technologies, and the outside factors that both push and pull on design consideration has given us a new lens on innovation.

As part of the 2015 docent education class and the “Intersections: Old and New Chicago” tour refresher-training, I explained the history and use of the term “Chicago School”; the challenges with using it to interpret buildings, and some suggestions going forward.

What follows is a summary of my recent lectures.

Basic Historiography

In 1932, Philip Johnson and Henry Russell Hitchcock curated an influential exhibition titled “Early Modern Architecture, Chicago 1870: The Beginnings of the Skyscraper and the Grown of a National American Architecture” at the Museum of Modern Art. The MoMa show, along with Sigfried Gideon’s “Space, Time and Architecture”, helped to popularize the hypothesis – one that became a dominant and unquestioned idea by the 1940s – that late 19th century Chicago architects were the immediate forerunners of European modernists. Gideon attempted to draw a direct line between the Reliance Building and Mie’s van der Rohe’s work. And in her book’s epilogue, Joanne Merwood-Salisbury does an excellent job of explaining the origins of these ideas from Johnson, Hitchcock and Gideon.

Creating the Narrative of a “School”

In 1964, working off his earlier writings, Northwestern professor Carl Condit published The Chicago School of Architecture. Trained neither as an engineer nor an architect, Condit was nevertheless most interested in the technology of early skyscrapers. It’s important to recognize that Condit took the approach of an art historian and thought about the Chicago School not just as an era but rather as a visual style with specific defining traits.

His influential text also sought to identify pioneering ‘firsts’ such as attempting to define and name a first skyscraper; he privileged William LeBaron Jenney as the father of the so-called Chicago School. As Bruegmann writes, “And, perhaps because he [Condit]) was an American living in the Chicago area, he was very ready to credit a Chicago architect, Jenny, with the creation of the first metal skeleton office building despite what had already become a considerable weight of opposing evidence.”

For more than 35 years, Condit’s book was the primary text for CAF’s docent training class. He also lectured here and at Glessner House on several occasions. Consequently, many of our docents who trained during those decades tend to organize the narrative of their historic tours around the Chicago School story, focusing more on the technical features of buildings (structure, materials) and less on the social, cultural, or even artistic aspects.

The Chicago School narrative also heavily influenced the city’s preservation and renewal battles during the mid-20th century. By linking threatened buildings to modernist designs, preservationists attempted to give Chicago’s early skyscrapers an historical pedigree and thereby legitimize them. As many tall structures became sorely neglected or were slated for demolition, preservationists united their efforts around a few prime examples, attempting to magnify the importance of any single building by unifying threatened buildings into a “school.”

But Condit’s boosterism and arguments – that Chicago School buildings were a “fully modern architecture, emancipated from the last vestige of dependence upon the past” – did not fit all the buildings from the era. His narrow use of the term “Chicago School” created new problems because, clearly, not all late 19th century tall buildings fit within a defined checklist of traits. As such, he tended to ignore or dismiss buildings with heavy ornament or historic references. (Marquette: “misguided traditionalism”; Old Colony: “a ridiculous colonnade.”)

Unintended Consequences

One unintended consequence of valuing certain buildings – those deemed “Chicago School” buildings – meant that others were devalued. Structures that did not meet an arbitrary checklist of features – an expressed steel frame, Chicago windows, tripartite division, etc. – were more likely to be demolished.

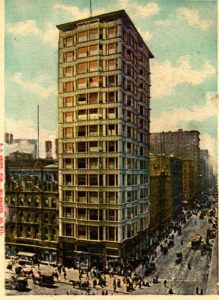

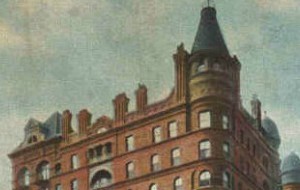

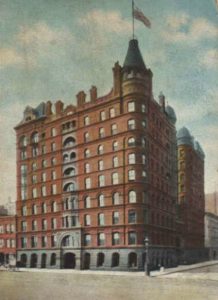

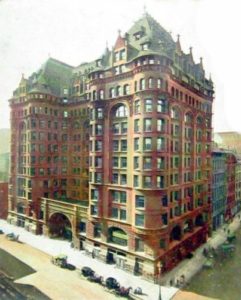

As contemporary historian Daniel Bluestone explains in his 1994 essay, in some cases the more “romantic” examples were easily dismissed by historians of the mid-20th century. The Columbus Memorial Building (W.W. Boyington, 1891), the Pullman Building (S.S. Beman, 1882), and The Woman’s Temple Building (Burnham and Root, 1890) were three casualties of the Chicago School focus. Their turreted towers, rusticated bases, and heavy ornamentation did not fit the “supposed ahistorical, structurally expressive model of the true Chicago Style” narrative, and thus it became harder to argue for their preservation. This, in part, explains why today many of the tall buildings in the Loop from this period look so similar. Structures that did not fit the preservationists’ constructed pattern, and thereby deemed non-Chicago School buildings, were more easily lost to the wrecking ball.

The View from 2015

Today however, architectural historians view this time period in a very different light, and they recognize the messiness of history. Scholars have new access to the writings of late 19th century architects; they recognize the diversity of structures (both technically and aesthetically) built in this time period; and they have a different vantage point from which to view the creation of a narrative built around the primacy of Chicago’s tall buildings. Today, most architectural historians simply don’t recognize the “school” as a school. Instead they use the term more in reference to show how mid-20th century historians viewed a curated collection of skyscrapers, rather than using it as a label, a building style, or a set of criteria.

Big Take-Aways / Summary

Where does this all leave us today? How do we understand and view late 19th century skyscrapers and, more importantly, how do we communicate those ideas to the public on a tour? Here are several big take-aways from the more recent scholarship and a summary of current thinking from noteworthy academics:

There is little evidence that the architects of late 19th century Chicago skyscrapers conceived of themselves or worked as a school self-consciously attempting to create a modern, structurally expressive style. (Bluestone, 1994).

In the 1890s, critics and observers considered the style of tall buildings as extremely eclectic. Skeleton construction and predominant height, more than a shared style or aesthetic, characterized early skyscrapers. (Bluestone, 1994)

In late 19the century Chicago, architects did not share a consensus on style or ornament or a design formula except within the production of single firms. (Bluestone, 1994)

“The idea of a skyscraper in Chicago in 1890 was not singular but multiple. It encompassed diverse thoughts about economic, social and a esthetic value… Debates about skyscrapers are inherently architectural and at the same time embedded within the broader social questions of the day.” (Merwood-Salisbury, 2009)

While the question of what was “first” and what was “modern” can be endlessly debated, Chicago can claim a legitimate role in skyscraper innovation. Because of many challenging conditions (soil, economics, materials, client needs, stylistic trends, history of the fire, etc.) architects could not follow ordinary methods of design. Instead they attacked the problems in new ways not seen before. (Leslie, 2013)

To use “Chicago School” or Not to Use “Chicago School” on Your Tour

Docents frequently ask how or if I use the term “Chicago School” when speaking about buildings. I tend to avoid it because I’ve found it’s not helpful for our audiences who are often thinking about architecture deeply for the first time. Current historical scholarship supports this as well. We’ve also stopped using the term “Chicago School” in recent CAF writings and videos produced for the public on architecture.org.

Other Suggestions

Today, some historians may use the term “Chicago Commercial” to indicate the building type of this area (its commercial function, method of construction, tall size) – but not in terms of stylistic criteria or visual. This is the approach we’ve tried to take in recent docent training classes and in language written for the building case studies on architecture.org.

Try to avoid making black/white statements about any building that does or does not fit a certain list of style criteria. While your tour takers may want an easy label for everything, acknowledge that because of the eclectic nature of buildings, not every building will fit into a neat style category… and that’s ok.

The story of Chicago’s tall buildings in the late 19th century is much more interesting than simply trying to compress everything into a “school” and give it a label. Let’s continue to explore different design lenses beyond a style label – technology, materials, politics, and economics, yes… but also social history, cultural history and aesthetics – in understanding the larger, richer and messier architectural story and Chicago’s role in creating these amazing structures.

One minor correction (I am astonished that Jen got anything wrong, even on a minor point!): Jen says about Carl Condit “Trained neither as an engineer nor an architect” However, according to Wikipedia, Carl completed his B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Purdue in 1936, and was “instructor in Mathematics in the College of Engineering at Cincinnati, 1942-1944. During 1941-1942 he also served as a Civilian Instructor in Mathematics and Mechanics for the United States Army. In 1944-1945 he was an Assistant Design Engineer in the Building Department of the New York Central Railroad in Cincinnati, the only architectural design he ever did himself.”

To think of the term “Chicago School” as simply an expression of style does not do the term justice..

Robert Bruegmann in his article “Myth of the Chicago School” not only expresses the misuse of the term but also why it is not going away.

He states, “From the vantage point of the 1990’s, both architecture and architecture history look quite different from the way they did in the 1960’s .Does this mean that the term Chicago school is itself useless and should be abandoned? Not necessarily. – Terms like “Gothic” or “baroque” were originally freighted with the negative polemics of one era but have survived by being overlaid with other kinds of polemics or by gradually losing their negative overtones to become standard art historical terms.”

” In this way, “Chicago School” might well survive as a term that includes not just the modernist, ahistorical Marquette building of the gridded structural expression but also the more recently discovered Marquette, with its richly ornamented walls of simulated classical masonry. It is an improbable transition but no less improbable than the vicissitudes that the term has already undergone. It almost died several times, but it has always returned to life. The Chicago School is dead. Long live the Chicago School.”

Given the manner in which historians, authors and critics from outside of Chicago use the term in the context of world architecture and the populist audience on our tours, the term “Chicago School” is not only appropriate but of benefit to understanding Chicago architecture in the context of all other architecture.

Re-reading this, I’m struck, as I was not in my earlier reading, by how certain ideas can become useful and timely tools toward an end while becoming dangerous in the long run. It’s most instructive that the idea of a definable “Chicago School” became a raison d’etre for preservation of certain buildings, but also spelled doom for other great buildings that didn’t fit the pattern. Jen says, “As contemporary historian Daniel Bluestone explains in his 1994 essay, in some cases the more “romantic” examples were easily dismissed by historians of the mid-20th century. The Columbus Memorial Building (W.W. Boyington, 1891), the Pullman Building (S.S. Beman, 1882), and The Woman’s Temple Building (Burnham and Root, 1890) were three casualties of the Chicago School focus. Their turreted towers, rusticated bases, and heavy ornamentation did not fit the “supposed ahistorical, structurally expressive model of the true Chicago Style” narrative, and thus it became harder to argue for their preservation. This, in part, explains why today many of the tall buildings in the Loop from this period look so similar. Structures that did not fit the preservationists’ constructed pattern, and thereby deemed non-Chicago School buildings, were more easily lost to the wrecking ball.”

What’s even more disturbing is that we latter-day observers, seeing only those very similar buildings, assume, even learn, that these buildings represent all the buildings designed in their periods. Worse, from our 21st century perspective, we can easily conclude that buildings like the Columbus Memorial, Pullman and Woman’s Temple Buildings must have been inferior in style and value to those that survived.

As we transition to a new location, it’s been interesting to hear the lament that we’re “losing” all “the best buildings.” While it’s true that some fine buildings will no longer be included on our core tours, we need to look at our newly included buildings with clear, unfiltered eyes. What, in and of themselves, do our new structures bring to the story of architecture in Chicago? They’re not tripartite? They lack terra cotta? Well, what happens if we look at what they have, rather than what they do not have? What if that “school” we’ve so loved talking about does not apply? What does apply? How do we define “exciting” or “worthy”? We have a rare opportunity to expand the story we’ve been telling. We might even help redefine and refine our city’s ideas about itself. How often does that happen?