By Kevin Griebenow, Class of 1993

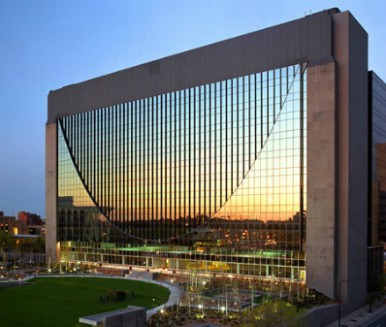

Blair Kamin’s obituary of Gunnar Birkerts (Chicago Tribune August 16, 2017) really connected with me when I read that he was the architect for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, now the Marquette Plaza. Why? Because this building connects the catenary arch with the concept of universal space, so important in Chicago’s architectural history.

My favorite example of universal space is the Inland Steel building, with open floors 175 feet by 60 feet. In the 1950s, this open plan was truly innovative. It provided unmatched, flexible square footage to tenants. This clear-span construction was made possible by the use of 14 exterior supporting columns connected to 60-foot long girders. The entire floor plate could be used in any manner that suited the tenants’ needs.

By the 1970s, Birkerts had another idea for creating universal space. Architects and civil engineers have long been dependent on arches. These curved members span an opening that support loads from above, forming the basis for the evolution of the vault. A succession of arches allows for covered space below, as in an arcade. Birkerts’ design for the Federal Reserve revolved around the catenary arch.

Other types of arches are well known: rounded Romanesque arches, pointed Gothic arches, and lancet arches are only a few. The catenary arch takes its shape from the curve of a loose span of chain or rope, suspended from each end and supporting its own weight. Its shape is determined by gravitational pull.

Such a chain is purely in tension. Invert that shape, now supporting only its own weight and purely in compression, and you have a catenary arch. This is the most stable of all arches; all the forces are contained within the arch, not thrusting outside of it. Consequently, a catenary arch would not require a buttress of any sort. A well-known catenary arch is the 630-foot Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

While Mr. Birkert’s design for the Federal Reserve building was to create universal space, he based it on a curved line, the catenary, rather than a series of columns. His interest in the arch was revealed when he observed, “straight line geometry is very man made.”

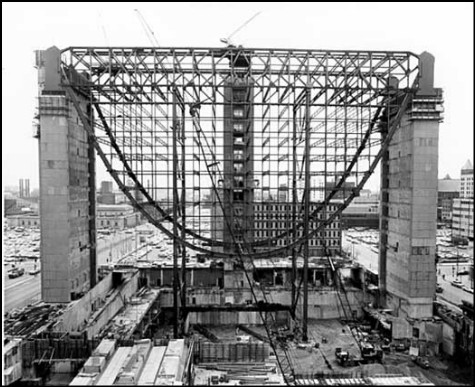

This bank building is essentially a series of bridge decks stacked on top of each other like a series of highways crossing each other. With each floor being a bridge deck, there are no columns intersecting the floors from end to end. These suspended floor plates can be clearly seen in the photograph of the building under construction.

The ground between the two ends of the building was left open to emphasize the bridge- like structure. Similar to the Inland Steel building, the structure housing the elevators is a vertical element external to the building. This elevator structure is visible behind the building, in the middle of the photo.

Understanding structure and the forces in the structure can unlock the science of skyscrapers. Comparing the Inland Steel building with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis is a study in the beauty of design, both solving the same problem of creating universal space, but approaching from different perspectives.

The next time you’re on the river or the River Walk, see if you can spot the catenary arch in a new building. Hint: look west!

Great article, Kevin – thanks!

Another architect to employ the catenary arch was Antoni Gaudi in his Sagrada Familia in Barcelona Spain. Gaudi hid the catenary arches within a design incorporating tree-like columns and branches.

Thanks, Kevin, for an excellent look at one of the architectural forms in one of our newest buildings. It’s a word to add to our vocabulary.

Ellen

Kevin, thanks for educating me—I really enjoy learning more about the techniques and technologies of construction. Hope you’ll find time to write more!

Thanks, Kevin. I remember an exhibit in Barcelona of suspended chains showing the shape of the catenary arch in connection with Gaudi’s frequent use of the shape. I never made the connection with the use here in Chicago.