by Steve Redfield, Class of 2019

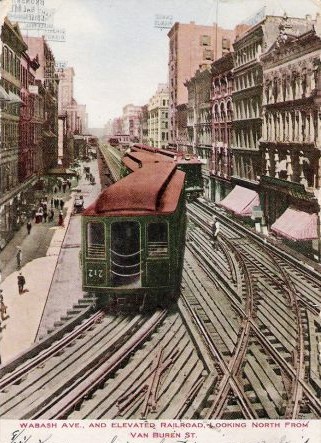

CAC’s “Elevated Architecture: Downtown ‘L’ Train” tour gives guests a unique opportunity to participate in Chicago’s transportation past, traveling around the Loop that opened 125 years ago. And they are indeed riding on history: the Chicago Transit Authority reports that 75% of the 24-block Loop still consists of the original structure.

Today, it seems hard to imagine Chicago without the Loop, and many people appreciate it as an icon that symbolizes Chicago. But nearly from its beginnings, there were efforts to tear it down. The first time a mayor called for demolishing the Loop was 1908, barely ten years after its opening. From 1927 to 1966, there were 10 different proposals to remove the Loop, often in favor of a subway system.

In late 1973, Mayor Richard J. Daley ordered the demolition of the Loop in private meetings with City and CTA officials – an action that, had it been carried out, would have thrown the transportation network into chaos, as there was no funding to replace it, let alone an actual replacement plan. (The State and Dearborn Street subways had been added in the 1940s to supplement the Loop, not replace it. Proposals to replace the Loop frequently proposed subways under Franklin and Monroe.)

But the Mayor’s public comments about removing the Loop brought proponents of the structure to the forefront, including the architect Harry Weese, who became one of its loudest defenders. He spearheaded a public opinion campaign that turned around public sentiment to save the Loop by arguing that, “what was needed was to recognize that the Loop was not only useful, unique, and functional but also, in its gritty way, fun.”

Weese had his work cut out for him, though. Paul Gapp, an editor for the Tribune who also took up the preservation cause, summarized the “Tear Down the Loop” camp’s point of view: “[Their view] sprang from the belief that the elevated was a steel noose around a dying downtown in strong need of massive upgrading…. It was strengthened by the exhortations of real estate men, some of whom believed dozens of old buildings in the Loop should be torn down as well.” Even the Landmarks Preservation Council (now Landmarks Illinois) made the extraordinary declaration that the Loop wasn’t worthy of being protected.

On the other side, people who joined the cause to save the Loop pointed out that the temporary construction jobs would do little to improve the city’s economy long term, and the removal of the Loop had racist overtones, based on an unspoken desire to remove African Americans from downtown after 5 pm.

After Mayor Daley’s death, Mayor Bilandic took up the demolition cause. As Patrick Reardon describes the era in his book The Loop, “The elevated structure, characterized as ugly and noisy and gloomy, had been at the top of the hit lists of two mayors – Richard J. Daley and Michael A. Bilandic – and an entire Mount Olympus of Chicago movers and shakers.” In the shadow of the wreckage of the ‘L’ crash of February, 1977 that killed eleven people, Mayor Bilandic used the accident as leverage on President Carter, attempting to secure federal funds for new subways to replace the “dangerous” Loop.

In 1978, Harry Weese and Judith Kiriazis, editor of Inland Architect Magazine, officially nominated the Loop to the National Register of Historic Places in an effort to secure its protection. That action would put a temporary hold on any federal money the city might request to remove the Loop and delayed any decision about its future while information and testimony was gathered for the preservation determination. This pushed the decision to 1979, when the city elected Jane Byrne as mayor. Byrne gave up the idea of the subways and instead established a committee to develop a master transportation plan for Chicago that included the Loop (with the CTA free to “rehabilitate, replace, or eliminate all but one of the Loop stations [which ended up being the Quincy station] but protected the structure from demolition”), thereby preserving the Loop we have today.

______________________________________________________________________________________

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Very nice article! I still remember the phrase “steel noose” as an argument to get rid of the L. I think the construction of Sears Tower in the early 70s helped remove the perception that you had to be within the L-track “loop” to be considered “downtown.”

Fascinating stuff Steve. I can’t imagine the loop without the loop. Thanks

Wonderfully enlightening story. Thanks!

Thank you for sharing this! I talk a little bit about the L on my River Cruise. This is great additional background!

Well done, Steve. You’ve nicely and clearly summarized the semi-public history of Loop preservation.

Thanks, Steve, for reminding us of the history.. the L is y ique in our history and Harry Weese is to be thanked.

Wonderfully enlightening article, Steve! I, too, talk about the “El/Union Loop” on my river cruises because it’s so visible and often noisy but also so much a part of our history. Plus, it’s functional, beautiful and just cool!

Really great stuff Steve. I have been riding the EL my entire life and couldn’t imagine the city without this iconic structure, and great transport system.

Grateful to know that Harry Weese played such a significant role in averting the Loop’s demolition.

I was manager of Operations PLanning at CTA at that time. There had been a proposal Chicago Urban Transit District to build a Loop subway and Monroe Distributor earlier in Daley’s reign, but funding and staging issues kept delaying it. The Loop subway was to be via Franklin, Van Buren, Wabash and Randolph I believe with Franklin being the first leg. The Willis Tower and Apparel Center across from the Merchandise Mart had provisions for a subway station entrance. But fortunately it all bogged down. I kep pointing out the downsides of the staging plans and was considered a negative force but for a long time the fix was in until the whole project died a/c public outcry and lack of $$$.

Fabulous article! Thannks!