by Ed McDevitt, class of 2010

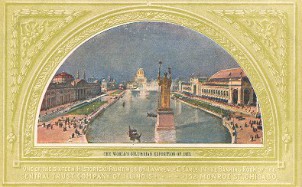

Among the old books donated recently to the Barry Sears Volunteer Library is one containing a goldmine of information about the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Rand, McNally & Co.’s A Week at the Fair, Illustrating the Exhibits and Wonders of the World’s Columbian Exposition with Special Descriptive Articles is a boon for history nerds!

This is a beautifully bound volume of 232 pages of double-column, 7.5 point text. It includes an index of two and a half pages, along with six pages of advertising before the title page and 21 advertising pages at the end of book. A map of the exposition is pasted on the reverse of the first page of the “Calendar of the Exposition.”

The book lays out an itinerary for each of seven days at the fair. It is obsessively detailed, including information for the first day—the railroad terminals where visitors might arrive, how to locate baggage, the hack and cab fares one might expect, and recommendations of places to stay, including a table of hotels near the fair, their meal plans, and rates.

A room was available at the Hotel Vendome at 55th and Monroe Ave. at $.50 per day for the European plan, the lowest rate. The Chicago Beach Hotel at 51st and Lake had rooms ranging from $4.00 to $15.00, the most expensive. In the downtown and “residence portion” of the city, rates went as high as $25.00 per day. For comparison, $1.00 to $25.00 in today’s dollars would be $34 to $855. A 7-day stay would have cost (in today’s equivalent) between $238 and $5,985. A day ticket to the fair was $.50 ($17 today). The average hourly rate of pay in 1893 for laborers was 14 cents. Clearly laborers weren’t going to the fair and staying in hotels; it would cost about half a week’s pay to attend the fair for one day, never mind seven.

The first chapter details information about hotels, baths, restaurants, “oyster saloons,” chop houses and the like. Women are admonished—“Ladies are not supposed to go to the chop houses. Their favorite luncheon places, when shopping, are at the magnificent restaurants provided in the great department stores.” The chapter ends with a long listing of “Places of Amusement” and Foreign Consuls.

Chapter II, “The Way to the World’s Fair,” is a dense compendium of information about how the exposition came about, what it cost, a glowing description of the site of the fair (“Nothing approaching it in beauty or extent was ever offered to any previous exposition”), a listing of all of the managers of the event, a table of appropriations made by foreign governments, and an essay by Daniel H. Burnham on “the building of the White City.” The chapter continues with detailed descriptions of exposition buildings, directions to the site of the fair, and information about how to enter and leave it: “In all there are provided for visitors to the park 326 turnstiles, 97 ticket-booths, 182 ticket windows, and 172 exit gates. There are also to be twenty-two ticket-booths in the business portion of Chicago.” And if you think ticket-hawkers outside Cubs games are a recent phenomenon, note this warning: “The visitor should refrain from purchasing admission tickets from street fakirs or strangers.”

It isn’t until the third chapter that we get to “The First Day at the Fair”.

The title page of the volume lists its “special descriptive articles.” The authors are many and include Mrs. Potter Palmer, Messrs. Adler and Sullivan, S. S. Beman, W. W. Boyington, Henry Ives Cobb, and W. L. B. Jenney.

The Preface states: “In almost every instance the architects of the chief buildings and the artists and sculptors themselves have described their work, and in such clear and forcible style that even the technical terms of their different arts are made plain to all. In this way alone was it possible to secure thoroughly accurate descriptions of their masterpieces. Realizing that whatever success this guide my attain will be largely due to this expert aid, the thanks of the publishers are hereby tendered to the eminent contributors whose names appear either upon the title page or included in [a list that follows].”

Beautifully drawn illustrations abound in the book. Here’s a typical example of two facing pages:

The advertisements in the book are fascinating. Here are some examples.

- Silurian: The Famous Waukesha Water. “Possesses Marvelous Curative properties in all affections [sic] of the Liver, Kidneys and Bladder.” The Silurian Spring Park was the development of David Smeaton, who marketed the spring site in Waukesha, Wisconsin for its health benefits in the 1870s. The site became a popular destination that, by 1893, included a roller coaster, a casino, and a theater – the Wisconsin Dells of its time. The company sold its water worldwide, along with ginger ale and wild cherry phosphate, all considered curative. The name for the Spring derived from the name of the sea that covered what is now the Great Lakes region at a time when the equator ran through North America. How clever to use a term that suggested great age of the water, and therefore ancient purity, even though most of the public had no idea what “Silurian” meant.

- Multiple ads for cultivating and harvesting machinery are no surprise. The most prominent was William Deering & Co., “the world’s greatest manufacturer of Harvesting Machinery.” The company merged with the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company and the Plano Harvester Company in 1902 to form the International Harvester Company.

- Gardner Sash Balance Company invited potential customers to send for a catalog showing images of “one hundred of the finest buildings in the world, all using the Gardner Ribbon” that supported the sash weights. This method of sash-weight hanging is still in use today, though the “ribbon” is now called a “tape sash balance.”

- Jones Business Colleges on Madison Street offered paid railroad fare and a “position” to “any young man or woman taking a Short-hand or Business Course at the college.”

- Hardy Subterranean Theater. This attraction, located on Wabash near 16th Street, was intended to give customers the sense they were descending well below the level of the street. The company formed in January, 1892, and engaged Herny Ives Cobb to design the theater. According to the Chicago Tribune, certain moving walls around five underground caverns would show visitors “a coal mine, an ice cavern, a scene from Dante’s Inferno, and a reproduction of Mammoth Cave.” The plan was to have it completed and open for business by the opening of the Columbian Exposition. Admission was $.50. Unfortunately, what was termed a “bed of quicksand” stymied progress on the project. It was abandoned in November, 1983, a month after the end of the Exposition.

- Buttermilk Toilet Soap: “For the Complexion . . . Makes the skin clear and soft, and leaves a soothing, beneficial feeling. Excels any 25 cent soap” 12 cents. Plus sa change . . .

Any Columbian Exposition researcher will find this remarkable book invaluable, as will an historian of the evolution of social mores and conventions. It is, to say the least, a wonderful addition to our collection despite its tiny typeface, which is not kind to old eyes.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Thanks, Ed. What a window to the Fair this book is. Does the library have a “rare book” collection area?

Thanks, Ed, a great introduction to a fascinating book!

For those who’d like to browse it but don’t have time to do so at the Barry Sears Library, since it is out of copyright, it is available to browse online, for example here:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t7br9pg9q&seq=7

Bob Michaelson

Fantastic find!

Wow, wonderful write-up, Ed. You’ve motivated me to want to read it (with a magnifying glass). Thanks, Bob for the link to the online copy.

I really appreciate your research and effort, Ed! Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Ed!!

Awesome Ed. Appreciate your article and your research!