by Tim Thurlow, Class of 2015

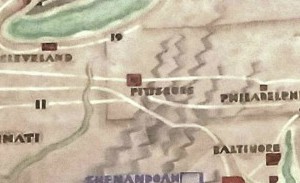

On the Walk through Time tour, docents enthuse over the vertical thrust and the deco ornamentation on the exterior of the former Chicago Motor Club [1928], designed by Holabird and Root. But inside, the most striking feature is the large lobby mural painted by John Warner Norton. Norton’s mural map of the United States shows long-distance auto routes. After gazing at the mural, someone often says, “I don’t see Route 66.” That’s not surprising since it isn’t there. Nor is any standard numbered route. Norton’s map captures the period before the adoption of route numbers. Instead, a key to the map lists 19 routes with names like Atlantic Yellowstone Pacific, Custer Battlefield Highway, and Old Spanish Trail.

Long distance travel had long been a monopoly of the railroads. To travel from New York or Chicago to a national park, people took a train. But by 1910 there were 500,000 registered vehicles in the United States. The number grew to 10 million by 1920, then 26 million by 1930. Early on, motorists yearned to take long trips by car. The American love affair with the road trip was beginning.

But could you depend on the roads? How easy would it be to find your way to a far distant destination? Around cities, roads were steadily being improved. But in rural areas, roads were often unpaved thoroughfares intended to serve local market towns. They were certainly not designed for cross-country tourists. Many states resisted investing on roads valuable for interstate travel, but with little local value.

Enter the era of trail associations. Boosters organized to create routes for motorists to reach popular destinations. Boosters would select a route over existing – sometimes barely existing – roads, give it a colorful name, form an association to promote the trail, and collect dues from the businesses and towns along the way. The associations published maps and brochures, held annual conventions and advocated for improvements in the highways.

The first transcontinental trail association was formed in 1913 to promote the Lincoln Highway, a route that ran over 3,000 miles from New York to San Francisco via Chicago. By the early 1920s, there were dozens of named trails – long distance ones, like the Old Spanish Trail, that ran from St. Augustine, Florida to San Diego, as well as short trails, like the Mohawk Trail, that ran from Greenfield, Massachusetts to Schenectady, New York.

These early routes could be confusing and signage was spotty. Local branches of trail associations would affix signs to trees and buildings, paint rocks, and sometimes enlisted Boy Scout troops to help out. In some places trails overlapped and trail associations competed with each other to attract the most traffic. In 1926, a national system using numbers rather than names was adopted. East-West transcontinental highways were denominated in multiples of 10. North-South routes would have numbers ending in 1 or 5, beginning with U.S. 1 – the route that runs down the Atlantic coast.

So how did we get U.S. Route 66? Cyrus Avery, an influential Oklahoma businessman and politician, argued that Route 60, running east from Los Angeles through Oklahoma, should then curve northward to Chicago, as commerce naturally continued in that direction. Kentucky opposed this route, expecting Route 60 to go through that state. If Avery’s proposal had been adopted, Kentucky would have been the only state in the union without a “0” highway. Furious at this omission, Kentucky threatened to walk out of the new highway system. A compromise was finally reached: Kentucky would get a highway 60, connecting to Avery’s route at Springfield, Missouri. Avery could get his Chicago-Los Angeles route if he would accept the number 62. Avery disliked the number 62, found out that 66 was available, and designated the Chicago-Los Angeles highway as U.S 66. The “Mother Road” was born!

So how did we get U.S. Route 66? Cyrus Avery, an influential Oklahoma businessman and politician, argued that Route 60, running east from Los Angeles through Oklahoma, should then curve northward to Chicago, as commerce naturally continued in that direction. Kentucky opposed this route, expecting Route 60 to go through that state. If Avery’s proposal had been adopted, Kentucky would have been the only state in the union without a “0” highway. Furious at this omission, Kentucky threatened to walk out of the new highway system. A compromise was finally reached: Kentucky would get a highway 60, connecting to Avery’s route at Springfield, Missouri. Avery could get his Chicago-Los Angeles route if he would accept the number 62. Avery disliked the number 62, found out that 66 was available, and designated the Chicago-Los Angeles highway as U.S 66. The “Mother Road” was born!

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge

I remember looking at this map every morning when I worked at the Chicago Motor Club during my summer high school vacations.

Never got tired of looking at it. Nice Article

Norton may have used traditional names, rather than new numbers, because the Motor Club preferred the names. The Club’s position was published in the Daily Tribune on April 25, 1926. The Club thought that numbers would be efficient but “impersonal”, while the names had “romance”, “adventure” and “historical significance”; as a result, the Club favored adding numbers while keeping the names — a compromise meant to satisfy both “the engineer and the layman”.

The trail associations opposed the adoption of the new system in 1926, claiming it would substitute soulless numbers for the romance of the road. That did not always happen. Route 66 is a case in point. I was browsing in the book department of the art museum in Albuquerque and came uponI a guidebook to Route 66 published in 2020. It notes the number of tourists wishing to take a nostalgia trip down the Mother Road, perhaps hauling an Airstream trailer, stopping at vintage motels, eating at diners, etc. The National Park Service has a Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program. There are now Route 66 associations in several stats.

Great article! I always think the mural is a highlight on the Walk Through Time tour, especially because the guests like having a reason to be inside for a few minutes on a cold day. These tidbits will definitely make it into my next tour!

Great story and explanation of what has been puzzling. Also, nice added detail by Bill.

Thanks for the very interesting and useful summary of early efforts to make it possible for people to find their way to a distant destination!

A slightly earlier way of guiding people was the use of photographic guidebooks, that seem to have first been developed by Homer Sargent Michaels in Chicago, circa 1905, and then taken over and published by Rand McNally under the name “photo-auto guide” or “photo-auto maps.” These were, as the name suggests, guides that presented photographs of landmarks on the way, to indicate where to turn – in the absence of highway names (let alone numbers)! The Newberry has a collection of about 20 of these guides, which you can locate with their online catalog https://i-share-nby.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/search?vid=01CARLI_NBY:CARLI_NBY&lang=en and the Chicago Map Society and the Newberry Library collaborated on publishing one Michaels’s first four guides, together with introductory materials and photos of the same sites as they look today (in 2008) –

Chicago-Lake Geneva : a 100 year road trip : retracing the route of a 1905 H. Sargent Michaels guide for motorists / compiled by

the Chicago Map Society. ISBN 091102882X

Great article! I love this mural. Two of my favorite things: the mountains look like tire tracks and Las Vegas is not on the map since it wasn’t a popular destination yet (construction started on Boulder/Hoover Dam and gambling was legalized in 1931, 3 years after the Motor Club opened).

I wanted to print out this article, but when try to print anything from the CAC weekly updates, the print runs together, and it is not worthwhile to print. Is this just happening on my computer, or do the rest of you have this problem? Is there a way we can access a print command that sets up properly? Thank you for this excellent article!

Thanks for your informative article. And for all the additional helpful information. I love maps and your article added to my knowledge collection. Appreciate the time you took to share this with us.