Editor’s note: With interest percolating in the media about the potential for “reimagining” Lakeside Center, we repost Bill Shapiro’s July 2016 Docent Quarterly article about the background and design of this architecturally significant structure. An ardent modernist, Bill retired as a CAC docent emeritus in 2021.

By Bill Shapiro, Class of 2000

The Lucas Museum controversy focused unusual attention on Lakeside Center at McCormick Place, one of the least known and least appreciated of the major works of Mid-Century Modernism. This should encourage us to take a closer look at the substantial architectural merits of the building. Unfortunately, the now universally condemned use of open lakefront land as the site for the building makes it difficult to objectively appraise the design. So the site and the design need to be considered as related but separate issues.

The site had been used for the Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933 and for fairs featuring railroad exhibits in the late 1940’s. The idea of constructing a permanent convention hall at this location took shape in the early1950’s with the strong support of Colonel Robert McCormick, the legendary publisher of the Chicago Tribune, and of Mayor Richard J. Daley. Despite massive opposition to the project, the combined clout of the Tribune and the Democratic machine eventually prevailed. Both the lakefront location and tax supported financing for the convention hall were approved in 1958.

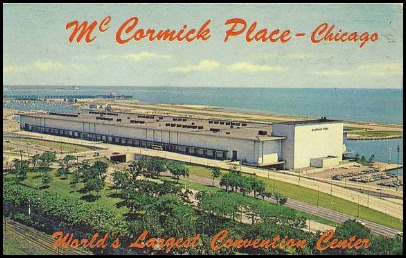

The building was completed in 1960. It was named for Colonel McCormick and designed by Alfred P. Shaw. Though Shaw had been one of the principal architects of the Merchandise Mart, the visual appeal of that monumental landmark was utterly lacking at McCormick Place. With its enormous walls of windowless concrete, the convention hall had the appearance and the charm of a giant warehouse. The distinguished Chicago journalist and historian, Lois Wille, described it as, “an immense, pale, squat cement box, heavy and graceless.”(1)

The building was completed in 1960. It was named for Colonel McCormick and designed by Alfred P. Shaw. Though Shaw had been one of the principal architects of the Merchandise Mart, the visual appeal of that monumental landmark was utterly lacking at McCormick Place. With its enormous walls of windowless concrete, the convention hall had the appearance and the charm of a giant warehouse. The distinguished Chicago journalist and historian, Lois Wille, described it as, “an immense, pale, squat cement box, heavy and graceless.”(1)

Surprisingly, in a city that should know something about fire, McCormick Place was built with inadequate sprinklers and fireproofing. An electrical fire following the installation of an exhibit destroyed the building in 1967. The city ignored this golden opportunity to relocate the convention center away from the lakefront and commissioned a new building on the same site. (While presently called “Lakeside Center,” the rebuilt convention hall was initially renamed “McCormick Place.” It stood alone until 1986, when the first of the three additional buildings was completed.)

The well-connected firm of C.F. Murphy was selected by Mayor Daley as architect for the reconstruction. Murphy recruited Gene Summers to design the building, making him a full a partner in the firm. Summers had studied with Mies van der Rohe at Illinois Institute of Technology and had become one of his closest and longest serving associates. He had played a key role in a number of Mies’s most important projects including Federal Center and the Seagram Building.

Although he had recently left Mies to establish his own practice, Summers insisted, and Murphy agreed, that Mies be invited to join the design team as its senior member. Mies declined the honor, unwilling to involve himself at age 81 in such a complex and controversial project. Summers was motivated by more than affection and respect for his mentor. He was well aware that Mies had already created an unbuilt prototype for the modern convention center.(2)

In 1953, the South Side Planning Board, an urban redevelopment organization, had commissioned Mies to design a convention hall for a proposed site in a blighted area south of the Loop. Working with three of his graduate students at IIT, Mies prepared detailed plans and models for the project. Though Mies’s proposal stood no chance of winning out against the politically favored McCormick Place, its architecture and technology were vastly superior.

In 1953, the South Side Planning Board, an urban redevelopment organization, had commissioned Mies to design a convention hall for a proposed site in a blighted area south of the Loop. Working with three of his graduate students at IIT, Mies prepared detailed plans and models for the project. Though Mies’s proposal stood no chance of winning out against the politically favored McCormick Place, its architecture and technology were vastly superior.

Mies’s plan provided over one half million square feet of totally column-free space with an 85 foot clear height. It fulfilled his vision of “universal space” adaptable to virtually any function required by future users. In the absence of supporting columns, no ordinary roof structure could span a space of this size without collapsing under its own weight. So the plan utilized giant trusses to bridge the 720 foot distance from wall to wall. The roof was a grid of 30 foot deep trusses welded together. It was supported by trusses around the perimeter of the building. The structural system would have been fully visible through the glass curtain wall, in contrast to the opaque concrete slabs of Shaw’s McCormick Place.

According to his biographers, “Nothing Mies had ever done was as intellectually adventurous or as tectonically bold as the unbuilt Convention Hall. From within, the soaring roof alone would have inspired awe. From the exterior the trussed wall structure would be grandly legible”(3).

While Mies’s structural system was highly innovative, roof trusses had long ago made their appearance in buildings requiring exceptionally wide clear spans. In the early 20th century, Albert Kahn, America’s greatest industrial architect, began using them in the structures he designed for automotive assembly plants. Roof trusses were essential to the construction of aircraft plants requiring vast open spaces for assembly operations. Among these was the Glenn L. Martin Company plant in Baltimore, designed by Kahn, completed in 1937, and later used for the production of World War II bombers. (4)

While Mies’s structural system was highly innovative, roof trusses had long ago made their appearance in buildings requiring exceptionally wide clear spans. In the early 20th century, Albert Kahn, America’s greatest industrial architect, began using them in the structures he designed for automotive assembly plants. Roof trusses were essential to the construction of aircraft plants requiring vast open spaces for assembly operations. Among these was the Glenn L. Martin Company plant in Baltimore, designed by Kahn, completed in 1937, and later used for the production of World War II bombers. (4)

The powerful, streamlined, utilitarian forms of American industrial buildings had great appeal for the masters of European Modernism. Mies emigrated to the U.S. in 1938, just a few years before the construction of huge new armaments plants and the reconversion and expansion of existing plants for war production was launched on a nationwide scale. In 1942, Mies saw a photograph of the interior of the Martin bomber plant with its trussed roof and was deeply impressed. This inspired him to imagine such a structure as the outer shell of a column-free concert hall. To illustrate this concept, he created a photomontage in which the roof trusses are prominently displayed. The far more sophisticated truss system of the 1953 convention hall can be seen as a logical development of Mies’s thinking about structure, influenced by his understanding and appreciation of American industrial architecture. (5)

The powerful, streamlined, utilitarian forms of American industrial buildings had great appeal for the masters of European Modernism. Mies emigrated to the U.S. in 1938, just a few years before the construction of huge new armaments plants and the reconversion and expansion of existing plants for war production was launched on a nationwide scale. In 1942, Mies saw a photograph of the interior of the Martin bomber plant with its trussed roof and was deeply impressed. This inspired him to imagine such a structure as the outer shell of a column-free concert hall. To illustrate this concept, he created a photomontage in which the roof trusses are prominently displayed. The far more sophisticated truss system of the 1953 convention hall can be seen as a logical development of Mies’s thinking about structure, influenced by his understanding and appreciation of American industrial architecture. (5)

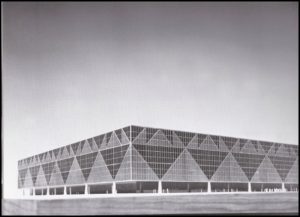

Mies’s ideas were clearly carried forward by Gene Summers in his design of the rebuilt McCormick Place. It has a black, steel and glass curtain wall, like other major works of Mies and his followers. While somewhat smaller than Mies’s convention hall and not completely column-free, the building provides great expanses of unobstructed space. The roof is supported by 36 giant, cruciform steel columns, eight of which are located in the main exhibition hall. The hall has a floor area of 300,000 square feet, a clear height of 50 feet, and bay widths of 150×150 feet.

Like Mies’s project, the roof consists entirely of trusses welded together. Also, the sides of the roof are open, allowing a full view of the structural system. The exterior columns are placed 25 feet outside the curtain wall, recalling similar features of Miesian designs dating as far back as the Barcelona Pavilion.(6) But Summers outdid his mentor by extending the roof trusses a full 75 feet beyond the columns. This awesome cantilever gives the building a dramatic profile, emphasizing its horizontal lines and suggesting a visual connection with the Lake Michigan horizon.

Like Mies’s project, the roof consists entirely of trusses welded together. Also, the sides of the roof are open, allowing a full view of the structural system. The exterior columns are placed 25 feet outside the curtain wall, recalling similar features of Miesian designs dating as far back as the Barcelona Pavilion.(6) But Summers outdid his mentor by extending the roof trusses a full 75 feet beyond the columns. This awesome cantilever gives the building a dramatic profile, emphasizing its horizontal lines and suggesting a visual connection with the Lake Michigan horizon.

Despite the seemingly endless controversy over its location, the architectural qualities of Lakeside Center have long been recognized by discerning commentators. Even Lois Wille, a severe critic of McCormick Place, praised the Summers design in her classic history of the lakefront. After describing the events leading to the reconstruction of the convention hall, she writes: “The best feature of the new McCormick Place was the building itself. With glass walls, exposed roof trusses and a see-through plaza to the lake, architect Gene Summers… succeeded in giving a light, airy feeling to a gigantic structure. It was an enormous improvement over the old concrete monolith.” (7)

Lakeside Center is a significant milestone in the history of Mid-Century Modernism. While strikingly original, the Summers design reflects the influence of Mies and, more generally, the impact of American industrial architecture on Modernism.

Sources:

- Lois Wille, “Forever Open, Clear and Free,” (University of Chicago Press, 1991), 116.

- Oral History of Gene Summers, Chicago Architects Oral History Project, The Art Institute of Chicago (1993).

- Franz Schulze & Ed Windhorst, “Mies van der Rohe,” (University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 317

- Hawkins Ferry, “The Legacy of Albert Kahn,” (Wayne State University Press, 1987), pp. 25,127, fig. 198.

- Schulze & Windhorst, p. 316.

- , p. 414.

- Wille, p. 119.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Thanks, Bill, for the extensive information!