By Emily Clott, Class of 2012

Before it goes “out like a lamb,” let’s acknowledge March’s Women’s History Month with pioneering architect Marion Mahony Griffin.

Born on Valentine’s Day, 1871, Marion was 8 months old when her mother carried her in a basket, fleeing the Great Chicago Fire. The family moved north and joined the Winnetka Unitarian community, a hotbed of progressive ideas. Set in a beautiful wooded area, the setting inspired her artistic nature. Her father died in 1883, and the family moved back to Chicago.

Mary Hawes Wilmarth, a family friend, recognized Marion’s artistic talent and paid her tuition to MIT’s School of Architecture. Marion’s cousin Dwight Perkins (Perkins & Will) also attended that same program, which could explain her interest in pursuing architecture. The quality of her renderings stood out for their excellence. In 1894, she was the second woman to have received a degree in architecture from MIT. Later she passed the Illinois licensure exam, becoming the first officially licensed woman architect.

Mahony-Griffin never lacked employment. She worked for Dwight Perkins for a couple of years, then was hired by Frank Lloyd Wright. While Wright didn’t hesitate to give her work, he refused to credit her for that work. A practice not unusual at the time, it persisted well into the 20th century.

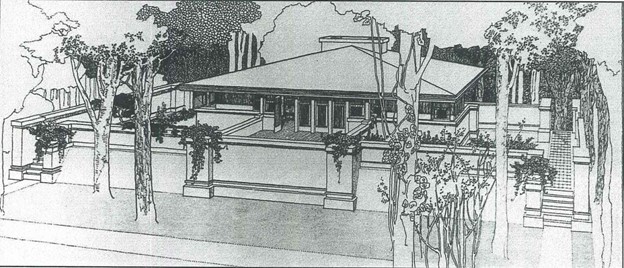

Contemporaries of Wright believed that many of his commissions were won due to the excellent delineation drawings Mahony-Griffin produced. Even Wright’s influential portfolio “Studies and Executed Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright” features Mahony-Griffin’s drawings; up to half the portfolio’s contents are her uncredited work.

Despite Wright’s failure to acknowledge her work, Marion was a close friend to his wife Kitty and an entire cadre of Oak Park women. That group included Mamah Borthwick Cheney for whom FLW would later abandon his wife and 6 children. When Wright ran off to Europe with Mamah in 1909, Marion harbored a deep contempt and resentment toward him that lasted the rest of her life.

Marion continued to work for Wright’s successor firm in a position of relative authority until 1911 when she married Walter Burley Griffin, a former colleague at Wright’s firm. Griffin was five years her junior, and unlike the fiery Marion, an introvert. Their differences did not get in the way of their marriage or their work. The couple worked together on major projects in Australia and India for decades.

In 1912, Griffin won the competition to design Canberra, the new capital city of Australia, quite a coup for an architect who was not well-known. Again, it was Marion’s impressive delineations that were a major factor in Griffin’s being chosen. The couple moved to Australia where they encountered many bureaucratic obstacles to achieving their plans for Canberra. Yet they stayed there through the nineteen-teens and twenties.

Mahony-Griffin seemed to have resigned herself to ceding credit for her efforts to her husband. Much later, in an unpublished memoir/autobiography “The Magic of America,” Marion identified the following as the three guiding principles of her life: first, she saw herself as an architect and professional with an artistic gift to integrate into a creative life; second, that she chose as her life’s mission to support and promote her husband’s work and his contributions to the field of architecture; third, that she hated Frank Lloyd Wright; she viewed him as having done irrevocable harm not only to herself and her husband, but to her mission—creating a progressive, democratic, modern American architecture.

When business in Australia slumped during the Depression, Walter Burley Griffin took commissions in India. At first, Marion stayed in Australia to manage the remaining business, but at his urging joined him in India. But in 1936 he died suddenly from peritonitis following gallbladder surgery; he was 60 years old. Closing up shop in Australia after Walter’s death, Marion returned to Chicago and wrote the unpublished autobiography mentioned earlier. But it seems her career ended with her husband’s death.

In Chicago there are two places to see Marion Mahony Griffin’s work, one solo, the other in partnership with her husband. The collaborative site is in the Beverly neighborhood. A section of 104th Place, with its seven homes the couple designed, has been landmarked and designated Walter Burley Griffin Place.

The solo work is a mural Marion painted at the George B. Armstrong School in Rogers Park, where her sister was an art teacher. The two-panel, 20-foot-long mural “Fairies and Woodland Scenes,” is located in the school’s main corridor and was completed in the early 1930s.

Marion Mahony Griffin died in poverty in Cook County Hospital in 1961 at the age of 90. She is buried at Graceland Cemetery, where the CAC Women of Influence tour helps to keep her memory alive.

Sources:

- Marion Mahony Griffin: Pioneering Women of American Architecture, pioneeringwomen.bwaf.org

- Chicago Patterns: Marion Mahony Griffin and Armstrong School, by Rachel Freundt. chicagopatterns.com

- Paradise lost: The forgotten landscape legacy of Marion Mahony Griffin. foreground.com.au

- Girl Talk: Marion Mahony Griffin, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Oak Park Studio, by Alice Friedman. placesjournal.org

- Walter Burley Griffin: In His Own Right. pbs.org

- The Unsung Architect: Marion Mahony Griffin-Stories of Her. harkaroundthegreats.wordpress.com

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Maybe we should have a tour of the mura some time.

“mural”

Well done, Emily!

Emily ,

Thank you so much for this fascinating, well written account of a talented woman who deserves to be better remembered. You mention how she was the second woman to graduate from the Schhol of Architecture at.MIT (the university was very progressive in admitting women. In all departments. )

The very first graduate was Sophia Hayden, who received her degree with honors in 1890.

Later known for designing the Women’s Building at the World Columbian Exhibition in 1893.

Thanks much for such an enlightening article, Emily! It’s also great to see you back working!

I enjoyed your well-researched and written paean to a woman architect worthy of greater recognition.

Wonderful article Emily! So interesting.

Oh, Emily, what a wonderful article. thanks for doing it and welcome back to our news crew on The Bridge. The information was wonderful. I knew a lot of this but never that she hated Wright. Not surprising, tho.