By Ellen Shubart, Class of 2006

In January 2017, my husband Richard and I visited Mexico City for a week. We spent two days visiting the architecture of Luis Barragan, resulting in this article about this unique architect. The sites listed here are those we visited.

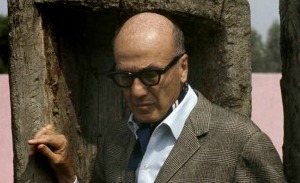

In 1980, Luis Barragan (born as Luis Ramiro Barragan Morfin), Mexican architect and engineer, was awarded the second annual Pritzker Architecture Prize. Not much known outside of his home country, Barragan was honored for his work as a modernist – although he has often also been called a minimalist. What is most impressive about Barragan’s primarily residential work is the use of color and light – rich, bright, huge splashes of color on the walls of his homes both inside and out, sun streaming through colored windows into large rooms and nooks and crannies, and the varied hues in the gardens outside that are so integral to the buildings. Barragan is described as “presenting a perfect example of the modernist reinvention of Mexican vernacular architecture (haciendas)” in a style that includes the use of color, light and water, and the interaction of inside and outside spaces.

In 1980, Luis Barragan (born as Luis Ramiro Barragan Morfin), Mexican architect and engineer, was awarded the second annual Pritzker Architecture Prize. Not much known outside of his home country, Barragan was honored for his work as a modernist – although he has often also been called a minimalist. What is most impressive about Barragan’s primarily residential work is the use of color and light – rich, bright, huge splashes of color on the walls of his homes both inside and out, sun streaming through colored windows into large rooms and nooks and crannies, and the varied hues in the gardens outside that are so integral to the buildings. Barragan is described as “presenting a perfect example of the modernist reinvention of Mexican vernacular architecture (haciendas)” in a style that includes the use of color, light and water, and the interaction of inside and outside spaces.

Born in Guadalajara, Mexico, in March 1902, much of Barragan’s early work can be found there. In 1936, he moved to Mexico City where he lived until his death in November 1988 at the age of 86. In 2004 his home and studio were named a UNESCO World Heritage site and are open to the public. It was in Mexico City that he designed his most iconic works.

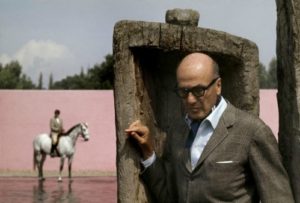

In his youth, Barragan was an “avid equestrian” and accomplished athlete. He told an interviewer that while out riding he noticed the play of shadows on the walls and the varying strength of the afternoon sun. These observations helped form his later architectural designs. Barragan’s initial and formal training was in engineering; he taught himself architecture after traveling in Europe, mostly in Spain and France, where he attended lectures by noted Swiss modernist Le Corbusier. In later life Barragan called himself a “landscape architect,” writing, “I believe that architects should design gardens to be used, as much as the houses they build, to develop a sense of beauty and the taste and inclination toward the fine arts and other spiritual values.”

A quick look at Barragan’s Mexico City projects:

Casa Luis Barragan, House and Studio (Tacubaya, Mexico City); 1947; UNESCO World Heritage Site 2004

Barragan lived in this home in the years following World War II. Built in 1947, the house reflects his design style at that period and remained his home until his death in 1988. Today it is a museum.

Barragan lived in this home in the years following World War II. Built in 1947, the house reflects his design style at that period and remained his home until his death in 1988. Today it is a museum.

Placed dramatically in the center of his desk is the Pritzker Prize. The citation from the Pritzker jury reads, “We are honoring Luis Barragan for his commitment to architecture as a sublime act of the poetic imagination. He has created gardens, plazas, and fountains of haunting beauty – metaphysical landscapes for meditation and companionship.… for Barragan, architecture is the form man gives to his life …”

Casa Gilardi (Tacubaya, Mexico City); 1976 (Photos were not allowed at this site.)

Barragan’s last work, Casa Gilardi, was designed for a client who imposed two conditions: a huge Jacaranda tree was to remain on the patio, requiring the house to be built around it, and a pool was to be included. Occupying a narrow lot (10×36 meters), color dominates: the patio is vibrant purple; the indoor gallery to the patio is yellow from sun streaming through yellow plastic-treated windows; the pool has a red concrete wall in the midst of the blue-green water. “It doesn’t support anything…it’s a bit of color in the water for pleasure’s sake,” Barragan wrote.

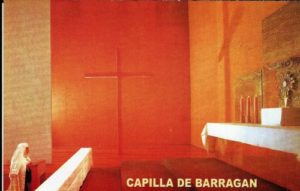

Chapel for the Sacramental Capuchin Nuns of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Talalpan a.k.a. the Tlalpan Chapel (Tlalpan, Mexico City); 1959

Barragan was a religious Catholic, and his work has been described as “mystical” and serene. We found this chapel by far the most stunning of Barragan’s work. The entry  patio is quiet, and the white cross on the wall across from the fountain is almost invisible. Inside, a simple cross that stands perpendicular to the altar has its shadow reflected on the same wall as the altar.

patio is quiet, and the white cross on the wall across from the fountain is almost invisible. Inside, a simple cross that stands perpendicular to the altar has its shadow reflected on the same wall as the altar.

The chapel was conceived through what has been described as “trial and error”. With the cooperation of Barragan’s friend Mathias Goeritz, he substituted a vertical white-stained glass window that lighted the chapel to a yellow one that provides more diffused light. The two also designed the golden triptych that serves as the altar.

The chapel is small but complex, with sections for the choir, a transept separated by a jalousie where visitors can worship, and a bench area for the nuns. The light that streams in was yellow in the winter when we visited. The nun who was our guide said that at other times of the year, red is the dominant color, reflecting the red/pink wall behind the altar. The suspended wooden cross is painted orange and, depending on where one stands, either stands out or dissolves into the wall behind it.

Casa Eduardo Prieto Lopez, 1950

The Jardines de Pedregal is a neighborhood in Mexico City where Barragan hoped to create a subdivision of custom-designed homes. The Casa Eduardo Preito Lopez is the only one of his designs that came to fruition. Included in the development’s design were public plazas and gardens, which weren’t built. The Lopez home, however, makes up for it all.

The Jardines de Pedregal is a neighborhood in Mexico City where Barragan hoped to create a subdivision of custom-designed homes. The Casa Eduardo Preito Lopez is the only one of his designs that came to fruition. Included in the development’s design were public plazas and gardens, which weren’t built. The Lopez home, however, makes up for it all.

The interior of the house is a Barragan interpretation of the traditional Mexican hacienda. The exterior and interior walls of the huge house are terracotta with large windows opening onto the gardens. Beamed ceilings alternate with carefully placed skylights and lightwells. The walls are bright pink, blue, and red. The gardens that surround the house on three sides are built over lava-based soil with spaces to sit and enjoy the outdoors. A pool sits in the L-shaped corner of the house.

This house was recently renovated under the sponsorship of the Barragan Foundation. The original colors, meticulously brought back to their original hues, compliment other acts of restoration. The Foundation also owns the Casa Barragan and the Barragan archives.

San Cristobal Estates equestrian development: House, Stable, Pools and Fountain (Mexico City); 1967

This is another attempt to design a residential development, and it is not as successful as Barragan hoped. Both the buildings and an entry fountain are considered the architect’s greatest late-period designs. The development features tree-lined avenues and tracks for cross-country horse racing.

The primary property includes more than seven acres of land. Currently occupied, the Barragan-designed main house is rarely open to the public, but the stables, a guesthouse, and pools are open to visitors. A central element in Barragan’s design philosophy is water—typically dropping from a height like a waterfall. It appears here in the form of two L-shaped swimming pools, one for horses and a smaller one for humans. The main walls of the horse pool are a rose-pink, while additional walls are painted deep purple, rust red, and stark white.

The entry to the development includes the Guente de los Amantes, or Lover’s Fountain; when we were there, the water had been turned off as a conservation measure.

The Towers of Satellite City (Queretaro Highway, Mexico City); 1957; in collaboration with Mathias Goeritz

Although this is listed as one of Barragan’s masterpieces, it’s hard to figure out the meaning of the concrete towers that just sit in the middle of a business district highway. Yes, they are colorful but otherwise, it’s unclear what or if they are supposed to mean or symbolize. For me, this was one of the few disappointments in Barragan’s work.

Although this is listed as one of Barragan’s masterpieces, it’s hard to figure out the meaning of the concrete towers that just sit in the middle of a business district highway. Yes, they are colorful but otherwise, it’s unclear what or if they are supposed to mean or symbolize. For me, this was one of the few disappointments in Barragan’s work.

In a lengthy article in the New Yorker magazine ( “The Architect Who Became a Diamond,” August 2016) author Alice Gregory unraveled the complicated path by which Barragan’s archives ended up in Birsfelder, Switzerland, where until recently, they were inaccessible to the public. The archives hold the negatives of photographer Armando Salas Portugal that document Barragan’s work. In addition it contains 13,500 drawings, 7,500 photographic prints, 82 photographic panels, 7,800 slides, 290 publications dealing with Barragan’s work, seven architectural models, manuscripts, notes, correspondence, and furniture. It will be illuminating when – and if – the archive is finally fully opened to scholars and students of architecture. Then we’ll know even more about the man who combined color and modernism to create such stunning masterpieces.

Sources:

- Wikipedia, “Luis Barragan”

- Alice Gregory, “The Architect Who Became a Diamond: A conceptual artist devises an ingenious plan for negotiating access to a hidden archive,” New Yorker, Aug. 1, 2016 (other version of the Aug. 1, 2016 issue contains the same article under the headline “Body of Work.”)

- Raul Ferrera, “Luis Barragan: Capilla en Tlalpan/Mexico; Fotografias de Armando Salas (Mexico: 2005 BarranFundation, Suiza)

- Stephen Silverman, “The Architecture of Luis Barragan,” self-published, 2013

- www.barragan-fundation.org

What a fabulous article! I love Luis Barragan– I was lucky enough to see some of his structures in Mexico City last spring!

-Patricia

Very interesting, Ellen. I think you’re right, that Barragan’s accomplishments have not been as noted as they should be. Re Satellite City, that was an arresting sight for me in 1963 as I visited Mexico for the first time, travelling by bus all the way from Chicago! Yes, I was young and enthusiastic. I view those pillars as just a statement of Mexico’s intention to “be important.” At that time, they were pretty much the northern boundary of the city. No more!!

Fantastic, Ellen. Thank you.

I’ll definitely go see his work when I’m in Mexico in August.

Ellen , Thank you so much. This article is just wonderful. Clearly, you must have done considerable research before your trip. Makes me want to re-visit Mexico City, which has many other architectural wonders, including lovely Art Deco.