By Susan Jacobson, Class of 2008

Every president who moves into the White House makes changes to the presidential residence, improving the infrastructure, redecorating public and private rooms, and adding amenities to reflect both his and his family’s tastes and interests. Chester Arthur was no exception.

Arthur became president in 1882, following the assassination of James Garfield, but he waited two years before he moved into his new home. President Arthur was not pleased with the appearance of his new residence. While the exterior of the presidential mansion had been maintained, the interior appeared shabby and run down, not at all to the tastes of this wealthy, Gilded Age New York City lawyer.

To achieve the look of elegance he desired Arthur hired the foremost interior decorator of the day, Louis Comfort Tiffany. Tiffany is believed by many to actually have been the first professional decorator to work on the White House.

Tiffany made major changes to the rooms of the White House. The East Room, the Blue Room, the Red Room and the Hall between the Red and East rooms were all redecorated. In the East Room, the ceiling was done in silver with a design in various tones of ivory The Blue room was decorated in robin’s egg blue, with ornaments in a hand pressed paper, touched out in ivory, gradually deepening as the ceiling was approached. The Red Room was the only complete interior Tiffany created. The marble mantelpiece was replaced by a new one of polished wood framing gilded Morocco panels, ornamental tiles, and brass. Various types of glazing were applied to achieve dramatically nuanced color in the walls and they were ornamented with a frieze in which the motif was an interlacing of a design embodying both eagles and flags. The ceiling was in old gold, with copper and silver stars that shimmered in reflection

Tiffany’s were the first White House interiors that made news. “A new era—the era of stained glass, tiled fireplaces and high mantelpieces—has dawned upon the White House. Estheticism reigns within its walls supreme. Peacock blue and silver, crimson brown and dead gold, delicate primrose and pale fawn—these are now the prevailing tints of the interior furnishings.” proclaimed The Washington Post, on December 20, 1882.

The highlight of Tiffany’s refurbishment was an elegant opalescent glass screen that stood in the entrance hall, replacing the “homely ground glass partition” which separated the corridor from the vestibule. An article in the Washington Evening Star described the screen as follows:

The highlight of Tiffany’s refurbishment was an elegant opalescent glass screen that stood in the entrance hall, replacing the “homely ground glass partition” which separated the corridor from the vestibule. An article in the Washington Evening Star described the screen as follows:

“It will have but two doors, the center of the screen being composed of one large panel. The center of this panel consists of a large oval, having four eagles arranged around a smaller central oval, which is a suggestion of the U.S. shield. The four rosettes which are outside the large oval in the corners of the panel have the cipher U.S.A. introduced. The whole panel is filled with innumerable pieces of different hued glass and crystal.”

Harper’s Weekly, in January 6, 1883, praised the new screen:

“Perhaps the most striking and original of the decorations is the screen which fills the arcade between the corridor and the vestibule. This is now a glass mosaic of varying but symmetrical patterns, composed of sheets of opalescent glass incrusted [sic] with vitreous jewels of topaz and ruby and amethyst . . . the centre [sic] of the central arch is occupied with a great oval composition of mosaic of yet more vivid and luminous colors. There is a quaint suggestion of symbolism in the four eagles which surround this and the rough monogram “U.S.” which appears here and there in opalescent glass; but these are quite incidental, and the motive of the work is purely decorative, and aims at harmonious and sparkling arrangement of rich color.”

Alas, Tiffany’s decoration lasted only twenty years. In 1920, Theodore Roosevelt ordered a complete refurbishment of the White House, under the direction of the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White. The elegance of Tiffany’s Victorian era decoration did not suit this rough-and-ready president, and all of Tiffany’s work was removed. Roosevelt is said to have demanded that the Tiffany screen be smashed to smithereens. (It is often thought that Roosevelt’s animosity to Tiffany may have been inspired by the bitter litigation and dispute with the town of Oyster Bay during Tiffany’s acquisition of the property for Laurelton Hall which had previously been public picnic grounds.)

McKim, Mead and White, however, recognized Tiffany’s artistry and instead of demolishing his work, they auctioned off the major pieces. On January 21, 1903, the screen was auctioned off as  “boxes of glass” for $275. It was purchased by Turner A. Wickersham, a real estate agent for a Chesapeake Bay resort development, and part of it was installed in the Belvedere Hotel in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. In 1923 a fire destroyed the hotel building – as well as its famous screen.

“boxes of glass” for $275. It was purchased by Turner A. Wickersham, a real estate agent for a Chesapeake Bay resort development, and part of it was installed in the Belvedere Hotel in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. In 1923 a fire destroyed the hotel building – as well as its famous screen.

There are, of course, no color photos of the screen, but the circa 1889 black and white photograph (above left) by Frances Benjamin Johnston depicts the Entrance Hall of the White House, including the Tiffany screen.

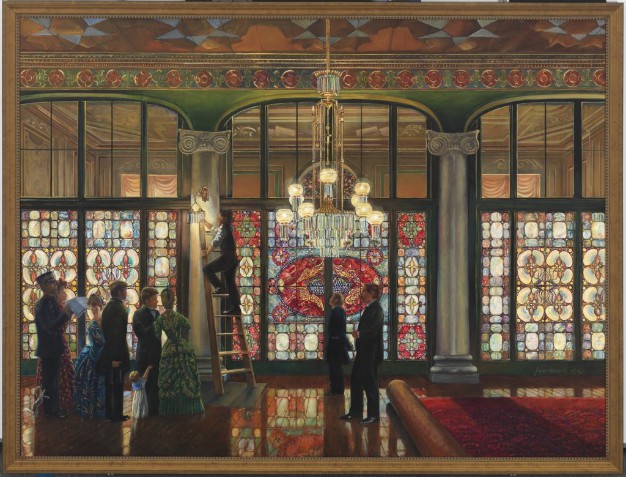

The modern depiction (right) painted by artist Peter Waddell for the White House Historical Association, shows the screen in color. “The Grand Illumination, Sunset of the Gaslight Age, 1891” focuses on the introduction of electricity to the White House. Waddell based his colors on contemporary descriptions of the screen, as well as on the colors used by Tiffany in the 1883 window dedicated to the memory of Nell Arthur, President Arthur’s wife, in Saint John’s Church in Lafayette Square in Washington, DC.

References

Arroyo, Nanette Marie. “Nell Arthur’s Memorial Window” White House Historical Association

https://www.whitehousehistory.org/nell-arthurs-memorial-window

Mitchelll, Sara E. Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Work on the White House. http://vintagedesigns.com/fam/wh/tiff/

Powell, J. Mark. Tiffany’s Extreme White House Makekover.

http://www.jmarkpowell.com/tiffanys-extreme-whitehouse-makeover

Seale, William. An Essay on “The Grand Illumination: by Peter Waddell. White House Historical Association https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-grand-illumination-sunset-of-the-gaslight-age-1891-by-peter-waddell

“A New Light on Tiffany” is in the docent library. It is about Clara Driscoll, one of Tiffany’s chief designers. She supervised the “Tiffany girls” who worked the designs and cut the glass. Tiffany paid the women the same as the men.

This is an excellent book. Enlightening!

barbara badger

Susan, this is just marvelous. Thank you for setting us straight about Tiffany and the White House! Joan

Interesting, Susan. Thanks fir a nice article with new, to me anyway, information. Ellen shubart

Thanks, Susan. Good article.

MOST INTERESTING, SUSAN. THANKS FOR ALL THE RESEARCH!

What a wealth of knowledge that you gathered! Thanks for sharing it.