By Bob Pratt, Class of 2019

Photos by the author unless noted

WKRP in Cincinnati, a hit CBS sitcom from 1978-82, could have been set anywhere. But series creator Hugh Wilson selected Cincinnati because “I liked the way it sounded … It rolled off the tongue very well.” But Cincinnati doesn’t just sound good, it looks good as well, due to its rich architectural heritage.

WKRP in Cincinnati, a hit CBS sitcom from 1978-82, could have been set anywhere. But series creator Hugh Wilson selected Cincinnati because “I liked the way it sounded … It rolled off the tongue very well.” But Cincinnati doesn’t just sound good, it looks good as well, due to its rich architectural heritage.

Cincinnati played a leading role in America’s early westward push thanks to its strategic location along the Ohio River. Cincinnati (originally Losantiville) was founded in 1788, incorporated in 1819. Once the largest city in the northwest territory, it served as a regional commercial center and transportation hub—the original “Porkopolis”. It lost those titles to Chicago shortly after the Civil War, although it continued to grow and prosper.

Cincinnati has a big story to tell, so I’ll tell it in two parts. First, I’ll review many of the architectural connections Chicago and Cincinnati share. Then next week, I’ll highlight notable architects whose Cincinnati works have no direct Chicago parallel.

Chicago Meets Cincinnati

Daniel Burnham’s legacy as an architect and city planner centers on Chicago, but his work and influence extend far beyond. Cincinnati is a major beneficiary of his genius. Over the period of 1901 – 1905, Burnham’s firm—D.H. Burnham & Company—designed four showcase buildings: three banks and one street-rail building. All are located within a two-block area. Three of the four Burnham buildings are being, or have been, adaptively repurposed: two hotels (Marriott and Kimpton) and one condominium loft conversion.

While each building is unique, all are classic Chicago-Commercial Style. They feature facades of brick, limestone, or terra cotta that express the underlying steel frame. At 239’, Burnham’s first bank in Cincinnati, The Union Savings & Trust Co., was Cincinnati’s tallest building upon completion in 1901. Note the tripartite design and Chicago windows around the building’s base.

The second Burnham design is the Tri-State Building (1902) for the Cincinnati Traction Company, featuring a pixelated dark-red brick shaft, topped by a massive cornice and several secondary cornices.

Architect: D. H. Burnham & Company

Burnham’s third Cincinnati design is the much smaller Fourth National Bank (1904), with lighter red brick and terra-cotta details at the top, in what one observer calls a “jewel-like” package.

Finally, the First National Bank, now Fourth and Walnut Centre (1905) is an imposing mass softened by banded and continuous horizontal spandrels, and subtle bays projecting from the front and side of the building, reminiscent of D.H. Burnham’s Monadnock and Reliance buildings in Chicago.

Cass Gilbert was born in Zanesville, Ohio, and is best known for his work in New York City and Twin Cities. Not only did he know Daniel Burnham, but his mastery of the Beaux Arts style associates him with our 1893 World’s Fair. Gilbert is renowned for designing the Woolworth Building in Manhattan, but in Cincinnati he, along with local architects Garber & Woodward, designed what in 1913 was the tallest building in the U.S. outside New York City – The Union Central Life Insurance Co. – standing at 495’ and 34 stories. At the time the tallest building in Chicago was the Montgomery Ward tower on Michigan Avenue at 394’. Instead of employing Gothic verticality as he did with the Woolworth building, Gilbert chose for Union Central Life a classical design clad in white terra cotta, featuring an Ionic-colonnaded temple above a heavy cornice, topped by a pyramidal roof and lantern.

The Union Central Life Building’s iconic status was confirmed when it appeared in opening and closing credits for both WKRP in Cincinnati and the long-running soap opera The Edge of Night. Today, it’s undergoing a multi-use conversion to include apartments and renovated office space.

Architect: Cass Gilbert

Walter Ahlschlager’s Chicago designs include the Medinah Athletic Club (now the Intercontinental Hotel) and the Covenant Club. In Cincinnati, Ahlschlager designed Carew Tower (1930-31) in partnership with New York’s Delano and Aldrich. Co-developed by Starrett Investment Corp. and Cincinnati businessman John Emery, this multipurpose development includes a 49-story office building and the Netherland Plaza Hotel. The tower features notched setbacks and soaring verticals, with a facade of granite, Indiana limestone, and buff-gold brick. Construction was completed within 13 months for a total cost of $33 million. Foreshadowing Bertrand Goldberg, Ahlschlager referred to the complex as a “city within a city,” as it included retail, office, an elegant hotel, an atrium, and a state-of-the-art parking garage. The interior of the hotel features lavish art deco designs. The Carew remains a prominent feature of the Cincinnati skyline and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as nationally significant.

Architect: Walter Alschlager

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s (SOM) Chicago credentials speak for themselves. But SOM has an outsized legacy in Cincinnati as well, beginning with the fact that Louis Skidmore was born nearby and began his architectural career there. Of greater importance, SOM’s pre-eminence in modern architecture was jump-started by a major Cincinnati project, the Terrace Plaza Hotel. Completed in 1948, this multi-use project has a 7-story retail base, largely windowless, topped by a slender 11-story hotel. Both sections of the Terrace Plaza feature thin, red face brick, clearly not structural as the vertical joints run continuously. It was a strikingly sleek modernist statement, designed by Gordon Bunshaft, Louis Skidmore, and pioneering female architect Natalie de Blois.

In addition to the building’s striking exterior, the upscale hotel featured fully automatic elevators and designs attributable to SOM’s new interior design department: innovative lighting and several works of art including an Alexander Calder mobile, a Joan Miro mural, and a locally themed mural by legendary New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg. After years of decline and a successful preservation effort, the building is currently being transformed into a multi-use structure including retail and residential.

Architects: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF) is best known in Chicago for the curving, contextual 333 W. Wacker Drive (1983). Contemporaneous with 333 W. Wacker, another major KPF project was the headquarters for consumer products giant Procter & Gamble which was completed in 1985. Like 333 W. Wacker, the P&G headquarters is a postmodern tour de force. New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger described it as “one of the most pleasing new buildings to be announced in some time … a respectful, yet inventive, homage to the finest eclectic and classical skyscrapers of the late 1920’s and early 30’s.”

Combining classical references with pure contextualism, P&G pays homage to several older buildings in Cincinnati that feature colonnades topped by pyramids (including Union Central Life). KPF’s design successfully blends the existing P&G office structures with its new, imposing twin-tower design. The building defines the northeast edge of the downtown area, and leaves a narrow space between the towers which suggests a gateway into downtown. KPF won an AIA National Honor Award for 333 W. Wacker in 1983, and for Procter & Gamble in 1987.

Architect: Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF photo)

Harry Weese, raised in Kenilworth, is one of Chicago’s architectural stars. He’s known here for his Time-Life Building, River Cottages, and the Swissotel. When asked by interviewer Betty Blum whether Time-Life (1968) was his most Miesian design, he said no, and pointed instead to his Formica Building (1970) in Cincinnati. He said it was “a true grid.” Travertine-clad and 14 stories, the building was part of Cincinnati’s downtown redevelopment plan. It included a block-long first floor atrium lined with shops, as well as an office structure and galleries for the Contemporary Arts Center.

Architect: Harry Weese and Associates

Cesar Pelli, born in Argentina, is a graduate of the University of Illinois’s architecture school and the former Dean of the Yale University School of Architecture. In Chicago, Pelli may be best known as the architect who designed the building that dethroned the Willis (Sears) Tower as the tallest building in the world with the Petronas Towers in Malaysia. More recently, his firm Pelli Clarke & Partners designed Salesforce Tower in the Wolf Point development.

In downtown Cincinnati, Cesar Pelli Associates designed a performing arts complex which revitalized a several-block area. The Aronoff Center for the Arts was completed in 1995 and features several theaters including the 2,700-seat Procter & Gamble Theater which is said to be modeled on Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Theater. The complex hugs the street and is largely glass along the streetwall and bounded by red brick masonry on either side. The transparent design invites a visual conversation between the street and the events on the inside. The red brick in this postmodern complex references other nearby landmark buildings, such as the Terrace Plaza Hotel.

Architect: Cesar Pelli Associates

Henry Cobb, co-founder with I.M. Pei of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, is the former chair of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. In Chicago, he is probably best known for his Hyatt Center (2005), at 71 S. Wacker, a striking 48- story office building with a convex glass curtain wall.

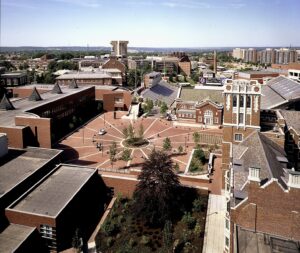

Cobb’s masterpiece in Cincinnati is on the University of Cincinnati campus, which Herbert Muschamp in the New York Times described as, “one of the most architecturally dynamic campuses in America today.” Cobb’s challenge was to reimagine that part of UC’s campus occupied by the College-Conservatory of Music (“CCM”), one of the country’s leading music and performing arts schools. The cramped setting with a hodgepodge of existing buildings was transformed over a seven-year period from 1992-99 into a mix of dramatic new classroom and performance spaces, preserved and modernized older buildings, and a new open feeling conveyed by a large courtyard with a circular driveway. Distinctive red brick, and the red-brick courtyard, pull together the CCM assemblage. Cobb’s CCM design received the AIA National Honor Award in 2001.

Architect: Pei Cobb Freed & Partners (Pei Cobb Freed & Partners photo)

Frank Gehry is a Canadian-American architect known for his sculptural and imaginative designs. In Chicago, the Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park stands as a prominent contribution to our city and its culture. Gehry has many international credits including the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

In Cincinnati, he contributed to the architectural showcase that is the University of Cincinnati campus by designing the Vontz Center for Molecular Studies (1997-99) on the edge of the UC Medical Center. The design features bulging walls and off-line angularity, with no effort to express the underlying structure. This was his first building clad in brick, perhaps due to economic considerations but also as a contextual reference to other buildings nearby.

Architect: Frank Gehry, (Waltek Company, Ltd. photo)

This article is part one of a two-part series, providing a brief overview of the outstanding and varied architecture of Cincinnati. While I have drawn on many sources for this article, the following comprehensive work on Cincinnati architecture was especially valuable: Painter, Sue Ann. Architecture in Cincinnati, An Illustrated History of Designing and Building an American City. Photographs by Alice Weston. Additional text by Beth Sullebarger and Jayne Merkel. Athens: Ohio University Press in association with Architectural Foundation of Cincinnati, 2006.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Nice article, Bob. It makes me want to go to Cincinnati. It was one of the “western” cities that Charles Dickens visited during his tour of the U.S. in 1842 when Chicago just getting started. Tom

Great photos and commentary, Bob. Cincinnati is definitely now on my list of places to visit. Maybe after Cleveland this year, we can go to Cincinnati next year.

Bob-this is an EXCELLENT piece! I lived in downtown Cincy (in Over the Rhine) for 16 years….loved it there. This article brought back so many memories of the city, the amazing architecture, & my life as what sometimes felt like an “urbam pioneer!” It was awesome to be in a place with so much history & fab architecture & very cool to see the downtown/OTR core grow & change. Who Dey! -kimberly

Thanks, Kimberly. Yes, OTR is another of the Cincinnati stories deserving of its own article. As you know, OTR is generally recognized as having the largest and most intact collection of Italianate architecture in the country. And the change from how OTR was (accurately) depicted in Steven Soderbergh’s 2000 movie “Traffic” is amazing.

Stay tuned for more!

Can’t wait for the second installment, Bob. I’m taking a class at NU with Henry Binford — whom we all remember from docent training I’m sure — and altho it is about Chicago, he is always talking about Cincinnati and its predecessor role to Chicago until the Civil War. I second Pris’ suggenstion that we go next to Cincinnati, after Cleveland this year. Thanks for a great overview.

Thanks, Ellen. When Professor Binford addressed my docent class (2019), he had to correct himself at one point after referring to Chicago as Cincinnati. He explained that he was writing a book about Cincinnati. Ever since, I’ve been watching for it. Perhaps he’ll tell your NU class when it will be published!

I would certainly be excited about a trip to Cincinnati, as you and Priscilla suggest, after Cleveland.

Bob – Great article. Here’s a link to Henry Binford’s recent book about Cincinnati. I think he has more coming out in the future. From Improvement to City Planning: Spatial Management in Cincinnati from the Early Republic through the Civil War Decade (Urban Life, Landscape and Policy)

Part of: Urban Life, Landscape and Policy (26 books) | by Henry C. Binford

Wonderful article, Bob. I have never visited Cincinnati, but I am putting it on my travel list now. Thank you for sharing.

Bob: Excellent article, well-researched, written and illustrated.

Thanks to all who commented. David, I will look for Prof. Binford’s book now that I know that it’s out there.

Thanks, Bob! Nice write-up and photos. I look forward to reading your Part II.

I have had Cincinnati on my To Visit list for awhile. I agree that this city would be a good candidate for a docent trip. I third Pris’ suggestion that we go to Cincinnati.