by Ed McDevitt, Class of 2010

As we have gotten more deeply into the details of our Barry Sears Volunteer Library, we on the CAC Library Committee are discovering how good our small collection of books really is.

Some of our books were donations that came from docents, authors, staff and, in a few instances, the families of colleagues who have passed away.

Recently we received a small private collection from a docent who clearly has a sense for books with high historical value. Two of them immediately caught my eye and bear description, which I will provide in separate essays for The Bridge. Both will be included in our developing Rare Books section in the library.

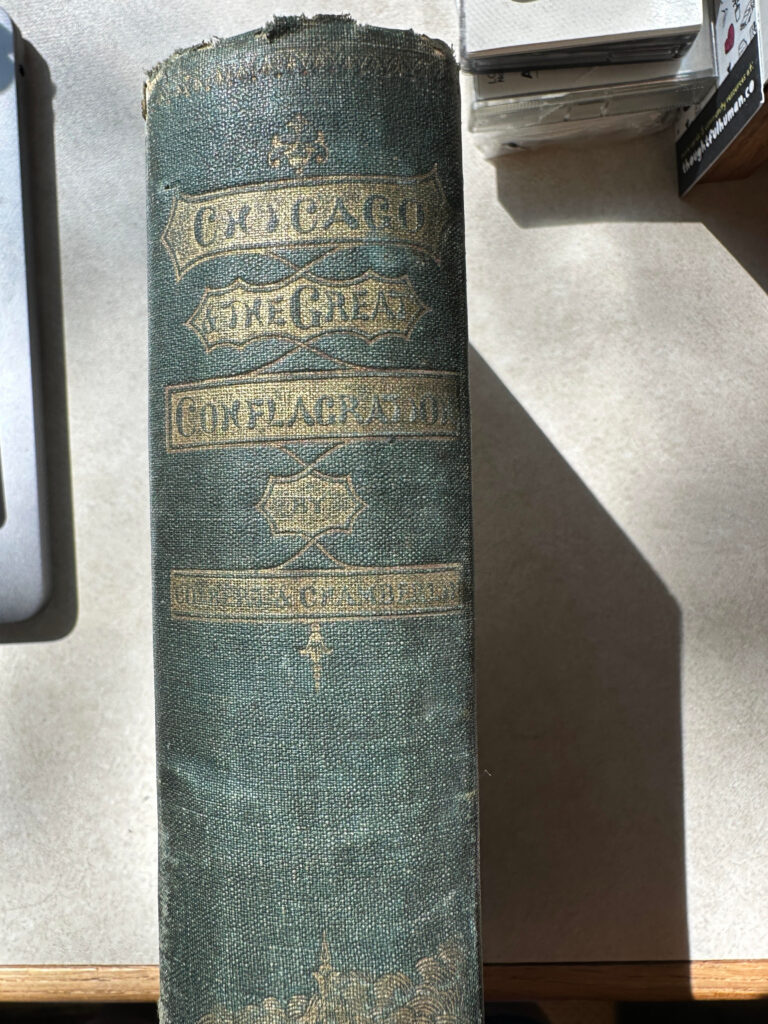

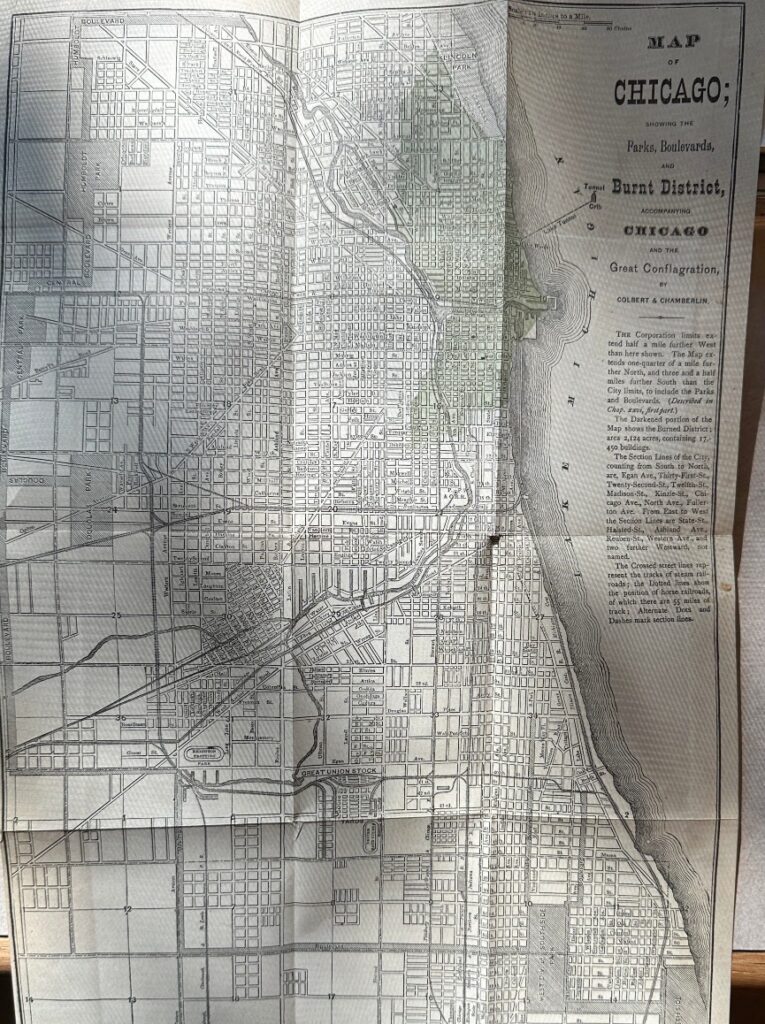

In 1871 Elias Colbert and Everett Chamberlin published Chicago and the Great Conflagration with Numerous Illustrations, by Chapin and Gulic, from Photographic Views taken on the Spot. This book seems to have started out as a history of Chicago from its “Aboriginal history” to publication date. That part of the book occupies 167 pages. It appears to this reader to have been ready for publication when the conflagration occurred. The book then acquired a rapidly assembled second section which is rather artfully woven into the narrative. The fire section has nearly 300 pages devoted to it. The illustrations “from photographic views” are professional drawings of buildings, including a few “before and after” depictions. Pasted into the book just after the Introduction is a fold-out “Map of Chicago; showing the Parks, Boulevards and Burnt District Accompanying Chicago and the Great Conflagration” (that map title, by the way, is printed in 7 different fonts).

Four appendices round out the book. Their contents are interesting by themselves. The first is “The Great Fires of History,” which lists fires and their destructive statistics. The most striking of these is the 19-page subsection on the deadly fire in Peshtigo, WI and surrounding counties on the same day, October 8, 1871, possibly the best account I’ve read of that disaster. The second appendix is “Documentary History of the Fire,” which provides letters and proclamations of support from all over the U.S.

The most interesting is Appendix C, “Contemporary Opinion Concerning the City and the Event.” The first few of these are laudatory, mostly from newspapers throughout the world. Then, abruptly, “Why she was Burned – A Rebel View,” written as a sort of OpEd in the Rushville, Indiana American. Rushville is a township southeast of Indianapolis, about 80 miles from Cincinnati and 160 miles from Lexington, KY. Keeping in mind that the Civil War had ended 6 years earlier and that Southern Indiana strongly supported the Confederacy. This editorial excoriates Sherman’s army, which in this account marched “robbing and plundering, and burning as they went, leaving the people to starve”; and the march through Virginia of Sheridan, “a monster of cruelty.” The editorialist says, “More property, and more lives were destroyed in these raids than all Chicago put together, and what was the sentiment of the North? One of exultation and rejoicing. . . . What cared [the post-war celebrating women of the North, including, apparently, those of Chicago] for the homeless, houseless, starving mothers and children of the South?” According to this essayist, the destruction of property in the South was “done purposely . . . and compares exactly with the acts of the Goths and Vandals, savages that overran and subjugated the Roman Empire. . . . Chicago did her full share in the destruction of the South. . . . Maybe with Chicago the books are now squared.”

Later brief essays suggest that Chicago “was punished for the sins of the world”; that the fire occurred because “the city recently gave a majority vote against Sunday and the Liquor Laws”; that the fire was a “retributive judgment on the city which has shown such a devotion in its worship to the Golden Calf.”

The authors list all of these reactions, positive and negative, without editorial comment. The opinions are not only historically valuable; they act as a sort of mirror of our own times. The book itself is a valuable compendium of on-the-scene history. It would take closer study to determine what is accurate, what is hearsay, and what is fanciful in the history, but the approach of the authors seems serious and earnest, with what appears to be strong documentation.

Appendix D is entitled “The Work of Relief: Report of the Philadelphia Committee,” which is an outside reflection on the efforts of Chicago relief organizations after the fire. Though he’s not mentioned here, one of the key figures in these efforts was Charles C.P. Holden, who built the spec building on Madison Street known as The Holden Block, featured on our West Loop Pub Tour.

We will give this book the care it deserves.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Thanks, Ed, What a find and what a wonderful addition to the Docent Library.

Tom

Thank you Ed for your fiery description of this rare and valuable treasure.

Thanks, Ed! I can only imagine the excitement you felt when you saw the book. So nice that it was donated.

Thanks for sharing Ed!

Seven fonts – design matters!!

Fascinating, Ed. Thanks for taking the time to share this and for everyone who contributes to the library.

wow! What a compendium of contemporary thought. I thoroughly enjoyed your review and look forward to looking at the book in the library. It seems to be a wonderful view into the mindset of the 1970s. Thanks much for the review and sharing, Ed.

Hi Ed! I have this book in its entirety