By Burt Michaels, Class of 2019

Historic Treasures tours start with the unforgettable Wrigley Building. Amazingly, the guy behind it, William Wrigley Jr. (1861-1932), was as attention-worthy as his fanciful headquarters.

A Quaker child in Philadelphia, Wrigley was unruly; he repeatedly got suspended from grammar school. As a pre-teen, he spent an adventuresome summer as a street urchin in hardscrabble New York City. He returned home untamed; at age thirteen he got still another suspension. This time his father yanked him from school and put him to work in the family’s soap factory.

But the confines and routines of a smelly soap factory hardly suited him, so Wrigley coaxed his father to make him a traveling salesman, and he did well as an itinerant. In 1885 he married Ada Foote; they had two children, Dorothy and Philip K.

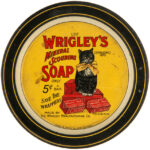

In 1891, with all of $32 in hand (around $1000 today), the family moved to Chicago, where Wrigley convinced a bank to front him $500— enough to open Wrigley’s Scouring Soap Co. To boost sales, he gave his customers premiums, like baking soda. When he saw they liked baking soda better than soap, he switched to selling baking soda—and gave them chewing gum as premiums. When he saw they liked gum more than baking soda, he switched to selling gum—made by Zeno Manufacturing–under the brand names Lotta and Vassar.

In 1891, with all of $32 in hand (around $1000 today), the family moved to Chicago, where Wrigley convinced a bank to front him $500— enough to open Wrigley’s Scouring Soap Co. To boost sales, he gave his customers premiums, like baking soda. When he saw they liked baking soda better than soap, he switched to selling baking soda—and gave them chewing gum as premiums. When he saw they liked gum more than baking soda, he switched to selling gum—made by Zeno Manufacturing–under the brand names Lotta and Vassar.

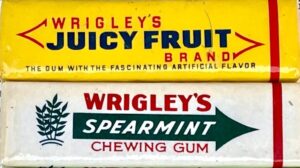

In 1893, for the World Columbian Exposition, he launched two new brands, Juicy Fruit and Spearmint, and invested heavily in advertising them. Like Quaker Oats, Pabst Blue Ribbon, Cracker Jacks, brownies, and other products that debuted at the fair, Juicy Fruit and Spearmint caught on big. Within five years, Wrigley bought out Zeno and took over manufacturing. Spearmint became the nation’s leading gum; Wrigley came out with Peppermint and other brands.

In 1893, for the World Columbian Exposition, he launched two new brands, Juicy Fruit and Spearmint, and invested heavily in advertising them. Like Quaker Oats, Pabst Blue Ribbon, Cracker Jacks, brownies, and other products that debuted at the fair, Juicy Fruit and Spearmint caught on big. Within five years, Wrigley bought out Zeno and took over manufacturing. Spearmint became the nation’s leading gum; Wrigley came out with Peppermint and other brands.

Though he spent millions on advertising–more than any other single-product advertiser in America–he put no signage on his headquarters. “People thought I’d plaster my name all over it in letters big enough to be seen miles away,” he told a reporter. “It was better advertising not to plaster my name on the building.” His restraint set the tone for North Michigan Avenue, where signage is strictly regulated.

And though he made millions, he cared about ordinary people. When he saw unemployed people camping out near the Wrigley Building, he retrofitted a six-story factory building as a shelter and funded the Salvation Army to run it. He boasted that gum is recession-proof, so he never cut workers or wages during downtimes. He was a major donor to the Progressive Party–and his son and successor as CEO, Philp K. Wrigley, was one of very few titans of industry who supported FDR and the New Deal. As a commissioner of Lincoln Park, Wrigley was instrumental in getting Oak Street Beach, a public amenity free to all, built.

Always a baseball fan, in 1916 Wrigley bought some Cubs shares. Within a decade, he’d bought out every other investor. He poured money into both the stadium and the team, hiring star players, and in 1929 the once-feckless Cubs won the National League pennant. He even let his club, the Chicago Athletic Association, adopt the Cubs’ logo.

Wrigley lived in a lavish penthouse on the Gold Coast; other family members lived at 1400 and 1401 North Astor Street and elsewhere nearby. There’s a memorial to him at St. Chrysostom’s Episcopal Church on North Dearborn Street, where he was a congregant. He also had an estate on Lake Geneva, six properties that represent more lakefront footage than any other estate.

He expanded westward, buying almost all of Catalina Island. He landscaped it with lush, exotic foliage, and built another mansion there. When he discovered valuable minerals and clay on the island, he started a mining company that gave locals good jobs. He built a casino and hotel and bought big steamships to ferry people to the island. The family later financed a nature conservancy there.

Wrigley then built an estate in Phoenix, near the Arizona Biltmore, and wound up owning that as well. Its architect, Albert Chase McArthur, had worked as a draftsman for Frank Lloyd Wright, who McArthur hired as a consultant on the hotel. Wright had designed a stained glass window for a magazine cover, and the hotel had it produced and installed in the lobby. Wright once claimed to have designed the hotel, then backed down and confirmed McArthur had.

He also had an estate in Pasadena that’s become the site of the Tournament of Roses.

Late in life, Wrigley claimed that despite his fortune, he lived a simple life and owned only three suits. Maybe, but he also owned five homes, the smallest of which was 16,000 square feet. Chew on that.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Terrific story. Thank you

I thought it was the other way around on the logo, started at CAA and then bought or taken by Wrigley for the Cubs.

Lots of interesting details. Thanks

Lots of interesting gems! Thank you Burt.

Love the pictures of the Wrigley houses. Tom

Great article Burt! Thanks!

Great article, as ever, Burt. Well-researched and written, with a good choice of photos.

Well done, Burt. Thanks!

What a great Story. Great job Burt! Thank you – Marisol

Very fun read, Burt. Gives me more to love about the Cubs and Wrigley! Thanks, Suzy Ruder

Great read, Burt! Thank you!

Burt:

You hit it out of the ballpark with this story. It’s amazing how each of us may define a “simple life.”

Thank you Burt – a very interesting article and photos. I recently visited the Wrigley Mansion in Phoenix. It is absolutely beautiful. You can take a tour on certain days and there is a restaurant open to the public that is divine.

Alison

Thanks, Burt, It sure is an interesting story about a fascinating guy. I loved the story and the pictures.

Really terrific article. Will definitely leverage on the River!