By Barbara Puechler, Class of 2006

The Willis Tower, that icon of Modernism on South Wacker Drive, is scheduled for something of a makeover. The $20 million expansion of the Skydeck is expected to include Ledgewalk. What’s Ledgewalk? Well, it will be an outdoor glass ledge where visitors can take in the views while enjoying fresh, rarefied air.

Sounds a lot like a balcony, doesn’t it?

As they have evolved, balconies have had a myriad of functions. They serve as platforms for political speeches, as at the Casa Rosa in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Crowds in Rome’s Piazza San Pietro watch as the Pope offers blessings from his balcony. During the Renaissance the purpose of a balcony was to allow more people a better view. In contemporary theaters, balcony seating is typically a less expensive option than adding seats on the main floor. Cruise ships offer staterooms with balconies, giving access to the outdoors, as a more luxurious experience.

As they have evolved, balconies have had a myriad of functions. They serve as platforms for political speeches, as at the Casa Rosa in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Crowds in Rome’s Piazza San Pietro watch as the Pope offers blessings from his balcony. During the Renaissance the purpose of a balcony was to allow more people a better view. In contemporary theaters, balcony seating is typically a less expensive option than adding seats on the main floor. Cruise ships offer staterooms with balconies, giving access to the outdoors, as a more luxurious experience.

When space is at a premium, balconies become a sought after feature for renters and owners alike, using the additional space for entertaining, a source of ventilation, or simply as a place to hang laundry. Balconies are not always on the exterior of structures. Internal balconies have been reserved for musicians and singers in churches, or as meditative places.

As balconies develop depth and increase in width, support from below is required. When support is integral to the wall itself, the supporting bracket is identified as a “corbel”. If the support is physically attached to the wall like a shelf, it becomes a “console”.

Wood was initially used in balcony construction as a supporting bracket. In some cases, stone brackets were used. During the Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) and the Renaissance (roughly 14th to 17th centuries) a construction technique was to use “corbels made out of successive courses of stonework, or by large wooden or stone brackets.” By the 1800’s, architects used a wider range of materials, examples being cast iron and reinforced concrete. Even today concrete is used for balconies that create a more private space.

Wood was initially used in balcony construction as a supporting bracket. In some cases, stone brackets were used. During the Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) and the Renaissance (roughly 14th to 17th centuries) a construction technique was to use “corbels made out of successive courses of stonework, or by large wooden or stone brackets.” By the 1800’s, architects used a wider range of materials, examples being cast iron and reinforced concrete. Even today concrete is used for balconies that create a more private space.

Style History

Style History

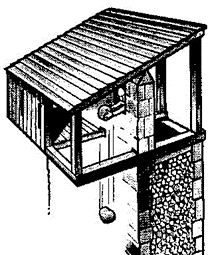

According to French architect Eugene Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (known for his restoration of medieval structures, 1814-1879) external balconies were integral “to an 11th century anti-siege device: the hourd.” In preparation for battle, or even during battle itself, the self-contained wooden enclosure could be installed quickly on a wall or support, allowing soldiers to drop stones and liquids through the floor. It was also a place from which to shoot arrows from above, while being protected from arrows and slings shot from below the extension. Visitors to Carcassonne, France, one of Viollet-le-Duc’s restorations completed in the mid 1800’s, can see a perfect example of the balcony-like hourd around the stone walls. These temporary enclosures, however, were largely abandoned by the 1300’s when battlements were built with more permanent stone.

In Britain, balcony styles used materials and ornamentation to reflect status. The “Juliet” balcony is a good example of design evolution. Generally thought of as protection in front of a window, the balcony was shallow, only the width of the window itself, and rectangular in shape. In the Georgian period (1714-1830), larger homes became more distinctive by constructing Juliet balconies out of wrought iron. Cast iron gradually overtook wrought iron, and metalwork became increasingly more ornate.

The short-lived Regency period (1811-1820) took advantage of the efficiencies of mass production to accelerate the use of the balcony to provide a measure of safety for the tall sash windows popular on urban town homes.

By the Victorian period (1837-1901), glass had become less expensive and less fragile, making it possible to use large panes for the new rage of “French doors” that brought natural light into those dark Victorian interiors. Architects used the Juliet balcony as a way of bringing the outdoors inside, also providing safety. A major change took place during the Edwardian period (1901-1910) when the width of Juliet balconies extended to two or more windows. The Juliet balconies enhanced the exterior of a building without overwhelming it despite the metalwork becoming progressively more ornate; it was light and airy.

Another notable style of balcony is seen primarily on the island of Malta. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site and considered “one of the most concentrated historic areas in the world.” The  Maltese balcony is the opposite of a Juliet balcony. The traditional Maltese balcony projects from the building, is primarily constructed from wood that totally encloses the space. While it can be painted in a variety of colors, a particular shade of green, a carryover from British influence, is the most common color.

Maltese balcony is the opposite of a Juliet balcony. The traditional Maltese balcony projects from the building, is primarily constructed from wood that totally encloses the space. While it can be painted in a variety of colors, a particular shade of green, a carryover from British influence, is the most common color.

On narrow streets, these jutting balconies create a particularly picturesque streetscape. Elaborate carvings are visible on many exteriors, embellishments that were purposely designed to ward off evil. The elaborateness of the balcony heralded one’s status. Wood being scarce and thus exceedingly expensive, only rulers could afford a wood balcony. When the British brought timber to the almost treeless Malta, this architectural feature was adopted by the wealthy. Over time the style filtered down to less prosperous classes. People used the balconies for additional living space and, of course, for hanging laundry.

The need for improved sanitation became essential during the cholera epidemic of 1865, and balconies were converted to water closets by adding drainpipes and privacy shutters. Not everyone rushed to convert the balcony to a water closet: “until 1967 in Valleta (capital of Malta) there were still 183 buildings with a common lavatory for all the tenants.”

Chicago, with its own great architectural history, is a good place to view the Juliet balcony as well as adaptations of the Maltese balcony. Walk down Dearborn, State, and Astor streets, north of Division Street, to spot balconies similar to those discussed here. Then, try to image how Ledgewalk, a balcony on the tallest building in Chicago, might work. Would you try it out?

Select References:

https://www.balconette.co.uk/juliet-balcony/articles/balconies-through-the-ages

https://www.britannica.com/technology/balcony

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-origin-story-balcony-180951755/

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/131

https://vassallohistory.wordpress.com/the-maltese-balcony/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corbel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bracket_(architecture)

Thanks, Barbara, for your excellent treatise on an often-overlooked element of architecture.

Thanks for the very interesting history!

An issue for balconies that is often ignored by designers of modern tall multi-unit residential buildings is very usefully discussed in the book by Christopher Alexander et al., A Pattern Languague: Towns, Buildings, Construction (Oxford Univ. Press, 1977) pp. 782-784:

“Balconies and porches which are less than six feet deep are hardly ever used.

Balconies and porches are often made very small to save money; but when they are too small, they might just as well not be there. A balcony is first used properly when there is enough room for two or three people to sit in a small group with room to stretch their legs, and room for a small table where they can set down glasses, cups, and the newspaper. No balcony works if it is so narrow that people have to sit in a row facing outward. … “