By Burt Michaels, class of 2019

Photographs by the author

For the second time in as many months, I found myself at a place meant to honor the dead, guiltily eyeing the architecture when I thought I should have been concentrating on the deceased.

The place in question is the American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, overlooking Omaha Beach. That’s where D-Day casualties were most horrific and where the Allied invasion was secured.

The cemetery’s architecture makes sense only in contrast to the architecture below, on the beach: steel sea walls so steep you can’t imagine anyone climbing them; iron Belgian Crosses to deter tanks; and huge, heavily-armed concrete bunkers. In sum, Hitler’s Fortress Europe—the Nazis’ massive defenses against an expected Allied invasion.

For me, the sea walls in particular resonated. Rising almost vertically, maybe twelve feet above the water at low tide, they’re daunting, seemingly unscalable. The image of thousands of young recruits, wave after wave, jumping out of makeshift landing craft to scale those walls while enemy machine guns strafed them from the bunkers above and the bodies of those who went before them floated by, I cannot grasp. Their fear, their courage, their conviction, the deadly chaos they moved through are alien to me. Thanks to them, the toughest challenge I’ve ever had to face was what? Maybe the GRE?

The cemetery was designed by the Philadelphia firm Harbeson, Hough, Livingston and Larson, and dedicated in 1956. The designers’ intent, it seems, was to let the heroes’ graves—numbering over nine thousand—express their valor without much architectural assistance.

Each grave is marked by a white-marble cross, except for those of Jewish soldiers, whose white-marble six-pointed stars seem to have the same circumference as the crosses. Eerily, the percentage of Jews buried there mirrors precisely the percent of Jews in the population. Sadly, the average age of the buried was 24.

The gravestones align precisely from any viewpoint, like the precision drilling of soldiers on dress parade. Quite a feat, as my 11-year-old grandson noted, since the designers back then did not have computers to give them an algorithm for how to pull it off.

The burial process reflected the democratic ideals for which the buried fought and died and to which we profess to value, if not realize. First come, first serve—privates next to generals, men next to women, Black next to White, all saluted with the same plain markers.

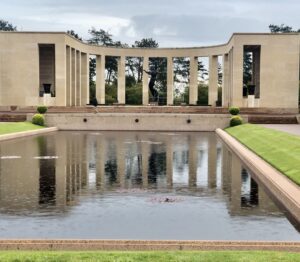

Most everything else is as stripped as the crosses, minimalist. There’s a semi-circular, neo-classical style colonnade whose columns are rectangular rather than round, like a stone henge—stark, no capitals. In front of the colonnade there’s a reflecting pool and further on, in the middle of the field, a small, round, inter-denominational chapel. Deco touches here and there. Deceptively unobtrusive and precise landscaping hiding this, revealing that.

The main exceptions being sculpture. At the front of the colonnade, a larger-than-life bronze sculpture, The Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves by Donald De Lue, strives to express in 3-D realistic/romantic stone what I could not in words—the incredible heroism of these youngsters. At the far end of the field, stylized pink-granite statues symbolically represent the bond between America and France.

The effect is serene, nearly perfect—order wrested from chaos, democracy prevailing over fascism. The U.S. offered to send all the deceased home for burial, and most families accepted. But about 40 percent chose to have their loved ones buried here, with their battle buddies.

I’m glad I brought my grandson here, that I was able to give thanks to those whose remains lie here. I hope he found a role model here, and that if and when his turn comes, he’ll stand up against the latest crop of anti-democratic racists.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

So moving. My wife and I recently visited too. Burt, you captured it well.

We were there a few years ago, also. Your description is excellent, as Bill said. The serenity of the cemetery and the beaches today belies the bloody chaos of the landing, while honoring the great sacrifice of those who died.

Thanks for the info. I visited in 2019 and also found it very moving. My father crossed the channel and landed at Omaha Beach 3 weeks after D-Day. He survived the war and I wished he could have been with me the day I visited. I kept thinking about the sacrifices these men made so that we could live the comfortable lives we live. We have no right no complain about anything!

Thanks for a great description of the place where heroes lie for eternity, a place that, once you have seen it, you will never forget.

When I was there some years ago, it was the end of the day and we took part in the flag lowering ceremony. Among the attendees was a veteran who had landed there. He received the flag at the end of the ceremony. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house. One of the most moving experiences of my life.

Well done, Burt. My experience was shortly after the 25th anniversary. I lived and taught in Lisieux and frequented these hallowed grounds. Still spine tingling. The French welcomed me with open arms telling me their stories about hiding American soldiers. They continue to be grateful for our support and recognize the terrible loss of life. My late father-in-law landed on Day 2 stepping over all the dead to secure the beach

Certainly, a time to remember, thank you for sharing.

Your description is very moving, Burt! Thanks for sharing, and glad that you could be together with your grandson during your visit.