by Ed McDevitt, Class of 2010.

by Ed McDevitt, Class of 2010.

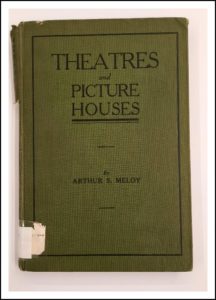

Into the late 20th century Meloy’s treatise on theater design was still a reference in landmarking determinations. It is cited in the 1987 New York City Landmarks Commission’s consideration of the Broadhurst Theater in Manhattan and also in the Landmarks Commission’s 1988 consideration of the Ed Sullivan Theater, where today’s “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” takes place.

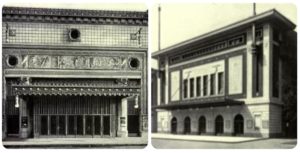

Of the eight theaters presented, two were in Chicago: the Orpheus Theater (1914, Aroner and Somers), then on Roosevelt Road at Ashland Avenue; and the American Theater (1914, Mahler and Cordell), then on Ashland Avenue at Madison Street.

While both buildings operated as Spanish-language movie houses until the 1970s, neither theater survives.

Docents who conduct the Walk Through Time tour will recognize that this book arrived on the scene a year before the Rapp & Rapp State and Lake Theater. Those who have conducted theater and other tours that include the Oriental (now the James N. Nederlander Theater) know that the infamous Iroquois Theater fire occurred on that site only 12 years before this book appeared.

Meloy’s book includes a “Table of Comparative Laws of Various Cities” (including Chicago) that stipulate such details as fireproof construction, minimum width of exits, minimum width of aisles with seats on one side, the number of steps in a balcony, the presence of standpipes and sprinklers, the use of fireproof paint and the like.

In Chicago, in the months after the Iroquois Theater fire, “many laws were enacted . . . requiring mandatory theater upgrades including outward-opening doors that remain unlocked, exit lights, automatic sprinklers, fire alarm systems, and flame resistant scenery, props, and curtains.” Meloy matter-of-factly notes that by publication time, only six states had established laws relative to theaters, Illinois being one of them.

Theatres and Picture Houses details theater design, down to the means of egress, proper stairway handrails, the dimensions and positioning of fire escapes, and much more. Of great interest is his warning about theater fires: that “there is more danger in a theater from panic than from fire.” Directly after this admonition, he includes a section on “Panics,” noting that “A panic may be just as disastrous in a fireproof building as in a cheaply constructed wooden building.” For Meloy, the blame for most “panics” resides in “some excited or highly nervous person” who reacts “for no good reason other than sudden fright caused by some fire scene on the stage, a loud noise, blowing out of a fuse, the darkening of the house without notice, the sudden lighting of footlights, the noise of passing fire engines on the outside, a thunder storm, a breaking of a seat, a sudden commotion in the auditorium, or other causes.” His was apparently not the age of evidence since he cites none for his list of possible theater panic attacks.

Unfortunately, little is discoverable about Arthur Sherman Meloy other than his presence in various census and government records. His prominence seems not to have been sufficient to have generated much historical interest beyond his book. We can thank him, though, for teaching us not to panic at the sudden lighting of footlights in a theater, a potentially valuable lesson.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Thanks for the article, Ed! I’m pretty sure I used this book when writing my (then-required) final paper during docent training on the Chicago Theater.

Thanks for the article, Ed. Interesting things I did not know — and those photos of the Spanish language theater are terrific.

Thanks for the nice review, Ed.!