By Bill Coffin, Class of 2004

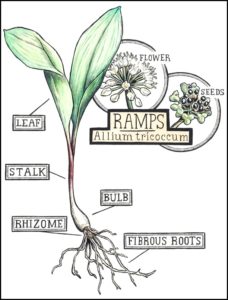

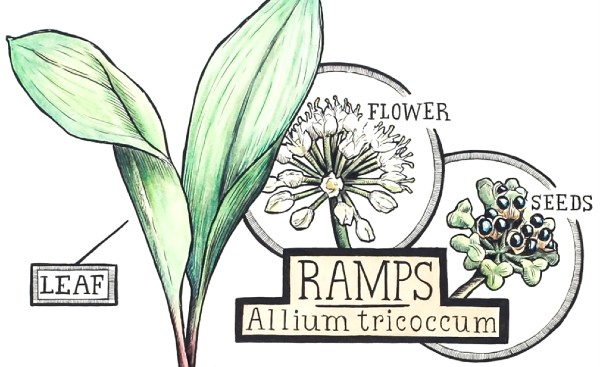

The name Chicago comes from the Indigenous Miami-Illinois word shikaakwa*, the name of a plant that most Americans today call wild leek or ramp and that botanists call allium tricoccum. The Great Lakes area is home to three native alliums, but shikaakwa refers to the only one that thrives in forests, has broad lance-shaped leaves and tastes like garlic not onion. It has a purple stalk, a white bulb and a white flower. Besides being edible, either raw or cooked, allium tricoccum is medicinal; Indigenous people used the bulb to treat stings and used the leaves to treat colds and the croup.

Because shikaakwa grew so abundantly in the surrounding forests, the south branch of the Chicago River was named for the plant. The south branch and the nearby Des Plaines River were separated by a portage, but they often overflowed and flooded together. Thus, the two rivers were regarded as one waterway and were given one name. Naming the waterway shikaakwa was a practical way to tell folks where to find the useful namesake plant.

Because shikaakwa grew so abundantly in the surrounding forests, the south branch of the Chicago River was named for the plant. The south branch and the nearby Des Plaines River were separated by a portage, but they often overflowed and flooded together. Thus, the two rivers were regarded as one waterway and were given one name. Naming the waterway shikaakwa was a practical way to tell folks where to find the useful namesake plant.

The word shikaakwa also meant skunk and may have been later applied to the plant because it, too, emits an odor when stepped on. And stepping on the plant would be hard to avoid in late March or early April when it is 8 to 10 inches tall and forms a green carpet under budding trees. In any event, the rivers were named for the plant, not the skunk. In the Miami-Illinois language, rivers were traditionally given names from one of three categories: the river’s characteristics, the names of tribes or people, or the names of plants or fish that lived near or in the river; rivers were not given the names of mammals.

When French explorers came to the portage in the late 1600s, they were keen to learn about native plants that foraging travelers could eat, and Indigenous people showed them shikaakwa. Henri Joutel, a deputy to René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, described in his journal shikaakwa’s unique forested habitat, broad leaves and garlic taste. He transliterated its Indigenous name to Chicagou – others wrote Chicagoua — and he called it ail sauvage in French, which translates to wild garlic in English.

Despite the general belief, the name Chicago does not come from the name of an onion. There may be a couple of reasons for the confusion. In the 1700s, for example, the majority of Indigenous people near the river were no longer Miami but Potawatomi, and the Potawatomi used the same word for both onion and garlic. Also, in the early 1900s, English historians incorrectly translated the word ail found in diaries of French explorers as onion rather than garlic.

Today, allium tricoccum still grows in area forests. The plants are called ramps in Appalachia and are celebrated at spring festivals. They are called ramps in some of Chicago’s finest upscale restaurants, too, and are served as a locally harvested, seasonal delicacy.

*shikaakwa is also written šikaakwa with a caron over the s to represent a “sh” sound.

Sources:

McCafferty, Michael. “Revisiting Chicago.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society vol. 98 no.1-2 (Spring-Summer 2005): 82.

Swenson, John F. “Chicagoua/Chicago: The Origin, Meaning, and Etymology of a Place Name.” Illinois Historical Journal vol. 84 no. 4 (Winter 1991): 235.

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge

Great article, Bill. So Chicago is not from the plant, but from a misunderstanding of the name by the English. Now we know better!

Thanks, Bill, for this extremely interesting and helpful clarification of the origin of our city’s name.

Excellent history of Chicago’s name origin. Thank you!

Bill – Also thanks for the photo – a very pretty plant!

Who knew that an Art Deco expert was also expert in Indigenous languages and a botanist to boot! Congrats, Bill, on a great article and one needed just now as we all ponder how to give information about the pre-Fort Dearborn era.

Thanks so much for the clarification!