By Brian Kelly, Class of 2019

The promise of opportunity has lured folks to Chicago for a very long time. The Native Peoples migrated in and around this trade center long before the steamboat or locomotive or semi-trailer or airliner arrived. All who disembarked from any of these long haulers added value to this special place. It took people with grit to make the journey and make their mark. Some are well known, others not so much. Here are four individuals who came, stayed, and left an indelible impression.

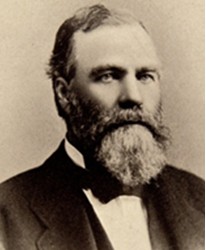

Martin L. Ryerson came to Chicago from New Jersey. He was a member of a proud and prolific Dutch family that immigrated to the New World in the middle 17th century. In 1834, Martin then 16 and with the help of his older sister, fled the family farm near Patterson and headed to Detroit, Michigan.

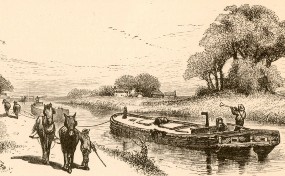

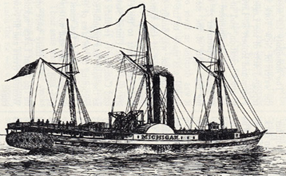

First leg of the journey was to New York City where he likely embarked on a seven-hour, $1 steamboat ride up the Hudson River to Albany. Second leg, an Erie Canal “Line Boat” to Buffalo was roughly a seven-day, $2 excursion. Finally at Buffalo, it seems Martin boarded a schooner and steamed about 300 miles across Lake Erie, a $3 passage. The entire trip from New York to Detroit in 1834 took roughly twelve days and cost $6.00 (~$190.00).

In Detroit, Martin was hired by an “Indian trader”, Richard Godfrey, to barter utilitarian goods (cloth, knives, kettles) for animal furs and pelts. They called upon the trading centers of Native Peoples. In 1835, he worked with Louis Campau, the father of Grand Rapids, Michigan, who traded with the Odawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe people. In 1841, Martin settled in Muskegon on Lake Michigan, bought a General Store, and managed the adjacent sawmill. He learned that Michigan yellow pine was a superior building material and it was in high demand.

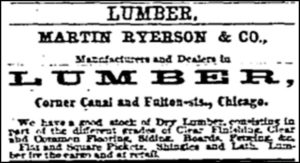

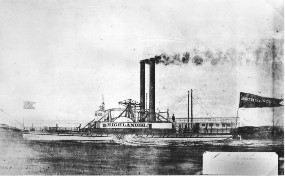

Four years later, Ryerson bought the sawmill and began land acquisition, harvesting, buying, and selling yellow pine throughout the states that lined the shore of Lake Michigan. He created an innovative supply chain establishing his own fleet of steamers to ply the waters and deliver directly to his yards in Kenosha and Chicago. His first Chicago lumber yard was established in 1851 on the north branch of the Chicago River at Canal and Fulton across from Wolf Point.

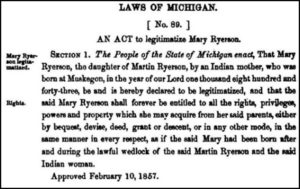

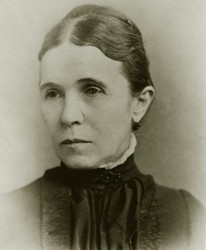

Martin was married to an Odawa woman, who died during the 1843 birth of their daughter, Mary. He fiercely defended the rights of his daughter and successfully petitioned Mary’s legitimatization as a citizen in 1857.

In 1855, Martin married Mary Ann Campau (niece of Louis Campau) and a year later Martin A. (Antoine) Ryerson was born. In 1857, to take full advantage of Chicago’s meteoric growth, Mary and Martin L. moved their family to Chicago.

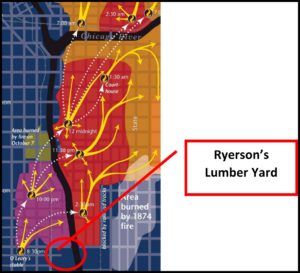

Chicago land prices maintained healthy growth in the post-War 1860s. In May 1870, Ryerson moved and opened an expanded lumber yard on the west bank of the south branch of the Chicago River where DeKoven and Bunker dead end into Beach Street.

Fortune smiled on Martin’s new lumber yard location as it was adjacent to the origin of the Great Fire when thirteen yards containing 60 million feet of pine lumber burned. According to the December 8, 1871, Chicago Evening Post, the Board of Police and Fire Commissioners investigation found that the yard was spared and firemen “paid no more attention to Ryerson’s yard than any other property.”

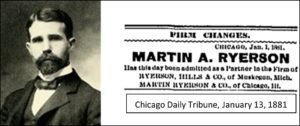

The lumber business was very good to the Ryersons. After all, Ryerson lumber built Chicago twice! In 1872, the family decamped to Paris while Martin A. attended school. They remained until 1876 when Martin’s schooling was complete. He matriculated at Harvard Law School and graduated in 1878. Martin A. joined the family business in 1881.

Martin senior withdrew from the lumber business, and like other wealthy founders turned to real estate development. In 1880, Ryerson began to acquire and improve lots in Chicago’s city center. He shared his time with civic philanthropic work. In May 1880, he was elected as both a Trustee and Board Member of the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1882, the Academy became the Art Institute. In the future, Martin junior would more than fill his father’s shoes at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Editor’s note: This story will continue next week on The Bridge.

CLICK HERE for more posts on The Bridge.

Very nice story…looking forward to next installment. These stories always provides nuggets that I add to my tours. Thanks..JP

Thank you, John!

Thanks so much for the informative article regarding the Ryerson family. Of course, I had seen that name countless times at The Art Institute…now I know some background of that philanthropy. And, yes, it will be a tidbit woven into a tour!

Thanks Suzy! Stay tuned, more to follow.

As always, Brian, you have a wealth of information about early Chicago. I enjoy reading it and am looking forward to the next part as well. Ryerson’s ties to the Indigenous peoples is very important, as it was his doing that created the Indian statutes in Lincoln Park now under discussion as to whether to keep them viewable. They are dedicated to the peoples of the Three Fires.

Thanks Ellen. The Dutch relation with Native Peoples was similar to the French, They worked to create a cultural “Middle Ground” , a non-coercive alliance system. Different approach from the British and Spanish.. The Dutch were the great traders and not as interested in colonizing the New World. Ryerson was part of this. So Ryerson is similar to DuSable. Ryerson married an Ottawa woman and DuSable married a Pottawatomi woman. “The Alert” was commissioned by Ryerson for Lincoln Park see Chicago Tribune May 6, 1884.

Thanks for sharing your bounty of research Brian. Fascinating! Looking forward to Part II.

Thanks, Elizabeth!

Thanks Brian. It was really interesting to learn so much I didn’t know about the Ryersons, plus all the information was framed in great storytelling with engaging graphics.

Well done. Another important contribution to the docent/volunteer community’s collective knowledge! I look forward to Chapter Two.

Thanks, Steven!