By Jim Bartholomew, Class of 2008

As the summer of 1918 gave way to fall, Chicagoans had already endured a tough year. January brought near panic with below-average temperatures in the upper part of the country; the resultant demand for coal had overtaxed the railroad’s ability to distribute it quickly. On January 16 the federal government ordered all manufacturing industries closed for five days and on each of the succeeding nine Mondays. That action put 600,000 individuals out of work. On January 20 Chicago started a series of ten consecutive “heatless Mondays” to conserve coal.

In what was probably a fairly chilly gathering architect Frank Lloyd Wright railed against his profession’s fixation with neo-classical design, saying, “We are plundering the old world of all its finery and dressing ourselves up in it as a kind of masquerade.” In May Mrs. Potter Palmer was laid to rest in Graceland Cemetery. On August 3, the Tribune reported that the Great Lakes Naval Training Station had 46,000 personnel at the base. Just a year earlier, there had been only 1,3000. On September 4 four people were killed and more than 30 injured when a bomb exploded at the Adams Street entrance to the Federal Building. Ten days later five people died and another 29 were injured when a freight train hit a streetcar in Pullman.

While all of this was taking place, a quiet killer was gathering strength. It began innocently enough … with a report on August 18 that four people had died of a mysterious illness on a liner docked in New York City with 21 additional cases on board. By September 12 the Port of New York was under quarantine. By September 15 there were 1,879 cases of influenza among soldiers and sailors in Boston with estimates that hundreds of civilians had the disease. Seemingly oblivious to what was headed their way, 133,000 people in Chicago gathered in Grant Park on September 2 to kick off the first day of the government’s war exposition.

By September 19, a thousand sailors at Great Lakes were in quarantine with the first case thought to have been diagnosed ten days earlier. By September 23, more than 4,500 cases had been diagnosed at Great Lakes with more than 100 dead because of the virus. Fort Sheridan, just a few miles to the south, reported 110 new cases on just the day of September 20, and the post was placed under quarantine at reveille. Ultimately, Fort Sheridan would fill the 54-acre parade ground with tents in a makeshift hospital that treated tens of thousands of patients. Seventy-seven deaths were reported at Great Lakes on September 26.

While the virus had affected mostly the soldiers and sailors on the North Shore, that containment would not last. Now the virus spread across the north suburbs. Theaters closed in Waukegan and North Chicago in late September. In Lake Forest police patrolled the streets, dispersing groups, while military troops did the same in Winnetka and Glencoe. By October 3 the Exmoor Country Club in Highland Park voluntarily converted its clubhouse into a hospital with a thousand cases reported in Highland Park and Highwood.

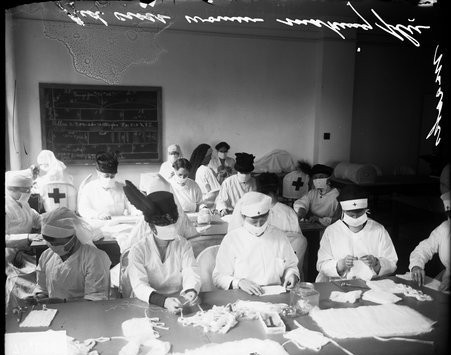

The whispers of the virus creeping into Chicago came on September 21, when health officials noted an increase in deaths related to respiratory failure, but by the end of the month only 260 cases had been reported in the city. Officials were concerned, though, and began to voice their fear that the city’s hospitals could be overwhelmed. Chicago Health Commissioner Dr. John Dill Robertson ordered, “Every victim of the disease is commanded to go to his home and stay there. No visitors are to be allowed.” Noting that children did not seem to contract the disease, the schools remained open throughout the run of the virus.

By the middle of October, 500 people were dying each day. Large gatherings—athletic events, banquets, clubs, activities in cabarets and dance halls—were banned. Public funerals were prohibited across the state. Streetcar operators kept the front doors open to keep a continuous current of fresh air circulating through the car. October 11 was the first night in almost 16 years that Chicago did not have a weekday public dance.

Yet on October 12, unbelievably, more than 100,000 people marched down Michigan Avenue, passing a reviewing stand of city dignitaries on the steps of the Art Institute; the Liberty Loan parade was organized to sell war bonds. A flier advised parade attendees to, “Go home, remove all clothing and rub the body dry and put on warm clothing. Take a laxative when you reach home, and you will minimize your chances of catching the disease.”

With 1,200 new cases reported each day and a peak nowhere in sight, the city moved toward a total shut-down. The Illinois Influenza Advisory Commission declared on October 15 “all theaters, movie houses, and night schools were to close immediately for an indefinite period, and all lodge meetings and other similar gatherings were prohibited.” Churches and synagogues remained open to continue charity work. Although the State Health Commissioner, C. St. Claire Drake, ordered all public gatherings not essential to the war effort be closed, saloons remained open, along with pool rooms and bowling alleys, “as long as they were properly ventilated.”

By October 21 the city received 100,000 doses of an “immune human serum”. As the first effective vaccine for a virus was not developed for another 20 years, it is unlikely that the serum turned the tide. Fortunately, by the end of October the daily death count was just under 200, and on October 29 the city began gradually easing restrictions, starting at Howard Street and working, day-by-day, to the south side. The ban on smoking on streetcars was not removed and is still in effect.

All told, in the six weeks from September 21 to the end of October, Chicago’s doctors and nurses attended to 38,000 cases of influenza and over 13,000 cases of pneumonia. Despite the death rate of 373 out of 100,000, our city fared better than others; Philadelphia lost 748 people out of 100,000. San Francisco 673. and New York 452.

It had been a devastating year, but joy came to Chicago and to the country on November 11, when Germany signed an armistice agreement in a railroad car outside Compiégne, France. That joy was tempered by the loss, in October, of 195,000 Americans, 80,000 more lives than had been lost in the World War. Between the war and the pandemic, the average life expectancy in the United States fell from 51 to 39 years of age.

But soldiers and sailors returned home, long-awaited work on the Michigan Avenue bridge began, and for another 102 years, Chicagoans lived free from the horrors of pandemic.

Resources:

Chicago Tribune archives

Chicago Sun-Times archives

Influenza Encyclopedia (influenzaarchive.org )

Well-written and sobering reminder that those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.

Only the names have changed, right? There are so many parallels.

Thank you for this excellent account of the 20th century flu pandemic. Isn’t it amazing how little progress we’ve made in the past century?

Amazing is a good way to put it!

Jim, Many thanks for your well researched and timely review. The striking details really resonate when they are local. -Susan Robertson

Imagine how overwhelmed those hospitals must have been! It boggles the mind to think that the original outbreak affected the North Shore first.

Fabulous coverage of the flu epidemic. Thanks, Jim. it is a comprehensive account and one, likely, we’ll all be including one way or another as we talk about this pandemic as well.

I left a lot of anecdotal details out for the sake of brevity. It must have been a very frightening time, especially with a war going on at the same time.

Good overview; thanks for posting it. Re: Liberty Loan parades, Carter Beats the Devil by Glen David Gold has a vivid and humorous

description of one in San Francisco.

on second thought the Liberty Loan scene may have been in Sunnyside, same author

My father had a 7-year-old brother who died in early 1919. The family story was that he was a victim of the epidemic. He was buried along with others on the east side of Bohemian National Cemetery (always described to me as a “mass grave” because there were so many to bury) until the family purchased a family plot and then was moved there. We’re hearing similar stories from NYC.