By Rick Lightburn, Class of 2008

Chicago’s many fascinating bridges are matched by many more “bridge nerds”, some with impressive and formidable credentials. While bridges don’t take tours, bridge nerds do, so you might encounter a few on your tours. (They can travel in packs!) A true nerd knows much more about bridges than you or I; they even speak their own language, a specialized dialect of civil-engineering-ese. These nerds can get excited, annoyed, and crabby if you mix up a queen post with a cross strut. You’re likely to encounter them when leading tours, so for the sake of their blood pressure—and yours—here’s some basic lingo.

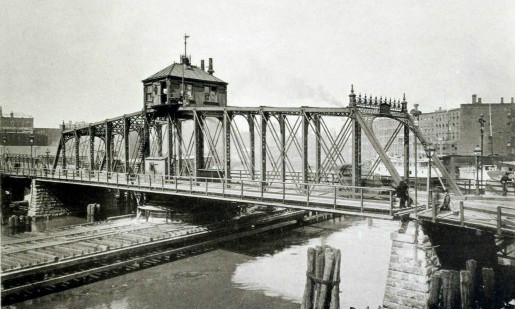

Almost all of the bridges here in Chicago are movable, and most of those are bascule bridges. Bascule is the French word for “rocker”, as in “rocking horse,” moving like the teeter-totters on a playground. Other types of movable bridges include swing bridges, which were important in Chicago history. Now there are only a few left, privately owned and rarely used. Amtrak trains running east from Union Station pass over a lift bridge just south of downtown. Many bridges in Chicago were originally movable.

Except for one, all of the bascule bridges in Chicago have trunnions. Trunnion comes from medieval French and means “axel”. So when bascules have trunnions, they turn on axels. The bridge on Cermak Road, where it crosses the south branch of the Chicago River, is the only trunnion bridge in the area that doesn’t have an axel. It is a rolling lift bridge.

Most of the bascule bridges that carry highway traffic have two leaves, while nearly all railroad bridges have only one leaf. A leaf is the part that gets raised and lowered. The two leaves meet (one hopes!) in the middle of the span; the span of single leaf bridges goes all the way across. While all bascule bridges have counterweights that allow them to open quickly, the counterweights are often hidden.

When I first came to Chicago, I was told that most of the downtown bridges were double-leaved trunnion bascule bridges. I had no idea what that meant, but it sure sounded impressive. Now I know!!

Most of the bridges are supported by trusses. Two bridges that don’t are at Columbus Drive and at Randolph Street; they use box girders instead. There are many types of trusses– Howe, Warren, Pratt, and so forth, so named for their inventors. Each has its unique features, but unless you’re a structural engineer, the differences don’t really matter. There’s even something called a “Vierendeel truss” that isn’t actually a truss, but acts like one. Tere are interesting examples, but not among Chicago bridges. The top and bottom elements of a truss are called chords, even if they’re substantial steel beams.

An important issue is where the roadway is located relative to the truss. The road can ride on top of the truss, or on the bottom, or halfway between. If the roadway is entirely above the truss, it’s called a deck truss. If it’s on the bottom, it’s called a thru truss. A pony truss is one where the roadway goes below the top, with no structure above the roadway, so most of the bridges that cross the river in downtown Chicago are pony truss bridges.

The McCormick Bridgehouse and Chicago River Museum (http://www.bridgehousemuseum.org/) in the southwest tower of the DuSable Bridge (Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive) is a great place to see behind the scenes of one of Chicago’s iconic movable bridges and practice your bridge vocabulary.