By Ellen Shubart, Class of 2006

Chicago’s city flag displays four stars. Two of them represent World Fairs, one for the Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the second for the Century of Progress of 1933-’34. Why were these such big deals for the city that they warrant placement on the flag with two other formative events for the city: the establishment of Fort Dearborn, 1803, and the Fire of 1871?

Chicago’s city flag displays four stars. Two of them represent World Fairs, one for the Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the second for the Century of Progress of 1933-’34. Why were these such big deals for the city that they warrant placement on the flag with two other formative events for the city: the establishment of Fort Dearborn, 1803, and the Fire of 1871?

Docents are aware that the 1893 fair proclaimed to the world that Chicago had risen from the ashes of the Great Fire and was now a proud, cosmopolitan city. Several buildings in Chicago’s downtown were built for or used around the time of the fair (the Art Institute of Chicago, the Auditorium Building and its grand Auditorium Theater, the Chicago Athletic Association men’s club, the Marshall Field Company Annex, even the 1871 Palmer House Hotel). Several new foods were introduced at the Fair (all-beef sausages, a.k.a. hot dogs, Cream of Wheat, Juicy Fruit gum, Cracker Jack). Fortunately, the great Museum of Science and Industry, which served as the fair’s Palace of Fine Arts, still stands. As a result, CAC offers a trio of tours about the fair: Devil in the White City, White City Revealed, and Food and Architecture of 1893.

Less is remembered about the 1933-’34 World’s Fair, perhaps primarily because none of the buildings is still on site. Five model homes from the Homes of Tomorrow exhibit are still extant, but they reside in Beverly Shores, Indiana. But perhaps it also is because the 1933-’34 fair, it can be argued, was less impactful than that of 1893. The purpose of this article is to compare and contrast the two fairs and let the reader make up his/her mind.

What, exactly, is a world’s fair?

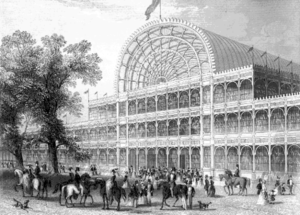

The dictionary defines a world’s fair as an international exhibition of the industrial, scientific, technological, and artistic achievements of the participating nations. In the eras before in the Internet, web streaming, and smart-everything, fairs were sponsored by nations to spotlight their industries, design, and manufacturing achievements. In short, it was “show-off” time for countries and companies worldwide, in an age when the “world” meant Europe, the United States, and Japan. Fairs originated with French national exhibitions that began around 1844. But the fair that gets the credit for kicking off the great series of 19th and 20th century world’s fairs was the 1851 “Great Exhibition” in London, organized by Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Housed in the magnificent Crystal Palace, it set the standard for what was to come in the next 100 years: gargantuan buildings where visitors could peruse manufactured and agricultural goods from around the nation and the world. It became a model for future fairs, and the Crystal Palace was a structure to be emulated or bested at subsequent fairs.

Historians rank fairs into three “eras:” The Era of Industrialization, 1851-1938; The Era of Cultural Trade, 1939-1987; The Era of National Branding, 1988-present. Chicago’s two fairs fit the first category. The Era of Industrialization was a time when fairs that focused on trade, displayed technological Inventions and advancements, and honored the state-of-the-art in science and technology.

The Era of Cultural Trade began with New York’s 1939-’40 fair where the emphasis was on intercultural communication. Typical themes included: “Building the World,” “Peace through Understanding,” and “Man and His World.” Also in this category is the 1967 Montreal Fair, the first to use the term “Expo”, and also, incidentally, named a baseball team. In the Era of National Branding, 1988- present, expositions were used as platforms to improve national images. Beginning with Expo 1988 in Brisbane, Australia, the most recent of these is Expo 2017, held in Astana, Kazakhstan.

Chicago’s Fairs: The Similarities

With apologies to Charles Dickens, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” … both times. Although both Chicago fairs were conceived of in prime economic times, by the time they opened, Chicago’s economy was not in good shape. In 1893, the national economy was entering what was then called a “Panic,” what today we would call a recession. The fair held the Panic off for a bit in Chicago but would hit right after the close. The city wrestled with massive problems brought on by waves of immigration: tenement housing, jobs, and labor unrest. In 1933, the U.S. was three years into the Great Depression, and the city was dealing with economic, racial, and labor issues.

Neither fair was purposefully designed to pull the city out of economic difficulties, but both aided the economy at a crucial time.

The 1893 fair was held on 633 acres in Jackson Park. Called the White City because the major buildings were constructed out of steel and “staff” – an erstwhile plaster of Paris mixture strengthened with hemp and horsehair — and spray-painted white. The fair had two sections. The first was the north-south axis where buildings displayed exhibitions, somewhat akin to Walt Disney World’s Epcot Center. The east-west axis ran along the Midway Plaisance and displayed exhibitions from “exotic” locations such as Cairo, Egypt, and Morocco. It was filled with beer halls, offered rides (on camels, in balloons or on a Ferris Wheel), and hosted displays of ethnic peoples and their dances and music. The fair drew 27 million visitors (at a time when the city had about 1 million in population) and cost $28 million to build.

The counterpart, 1933 Century of Progress, was spread along 424 acres on the shore of Lake Michigan, including what today is Northerly Island. In comparison to the earlier fair, this one was dubbed “Rainbow City” with buildings painted is myriad bright colors. Originally scheduled to run from May – October 1933, the fair was so successful that its run was extended another six months in 1934. In its two years of operation, it drew 40 million visitors with a cost of $100 million.

Both were celebrations of historic anniversaries. The 1893 fair recognized the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus to the “New World”. The 1933 fair acknowledged the 100th anniversary of the incorporation of the City of Chicago. Both buoyed Chicago’s and America’s hopes for the future. Both made money for their investors and both drew attendees from around the world. Both were known for their exotic, slightly naughty dancers – 1893’s Little Egypt who did the belly dance, and 1933’s Sally Rand, who danced the bubble dance wearing only fans.

Both fairs took us to the sky – in different ways. Visitors at the 1893 Fair could view things from above the ground via the tethered balloon, the electric railroad that ran in a crescent track and was the forerunner of the L, or, of course, via the Ferris Wheel. This structure was commissioned to “out Eiffel-Eiffel,” to be a phenomenal engineering achievement to outshine the Eiffel Tower that had been unveiled at the 1889 Paris fair. In 1933, the fair offered the famous Sky Ride, with double-decker gondola cars that ran along guidewires from one end of the fair to the other. For 40 cents a ride, riders had a sky-view from the height as tall as New York’s Woolworth Building, 625 feet up in the air.

Finally, both were criticized for their architectural impact. After the 1893 event, Louis Sullivan rather dourly declared the Beaux Arts style used at the fair had set American architecture back 50 years – and he may have been right. And an equally disillusioned Frank Lloyd Wright decried the 1933 Art Deco and Moderne styles – but that might have been because he wasn’t formally invited to participate.

Chicago’s Fairs: The Differences

But there were differences. In 1933 the exhibitions were designed to be more “doing” that “seeing,” that is they were actively producing products. A General Motors-Fisher Body Company assembly line rolled cars off as often as in Detroit, while at the Firestone exhibition, tires were assembled. The American Can Company stamped out souvenir cans, and Hiram Walker & Sons bottled Canadian Club whiskey. There even was a “working” coal mine, moved after the fair to the Museum of Science and Industry, where it amazes visitors to this day. The 1933 fair was a preface to America becoming a consumer paradise.

Importantly, the architectural emphasis was also different. In 1893, Daniel Burnham and his fellow East Coast architects popularized the Beaux Arts or neo-classical style with columns, domes, and Greek and Roman influences. The 1933 fair was purposefully futuristic, playing up the popular Art Deco style and its more industrial successor Art Moderne, with glass brick, sloped lines, and verticality as its watchwords. The Houses of the Future, including the House of Tomorrow/Glass House, the Enamel House, and the Stran-Steel House, highlighted the new looks. The House of Tomorrow, designed by George Fred Keck, was a 12-sided home that included its own airplane hangar and glass walls that offered views from all angles.

Despite its emphasis on the future, the 1933 Fair celebrated Chicago’s history. It included a wooden replica of Fort Dearborn, and publicly honored Jean Baptiste Pointe Du Sable, possibly for the first time, as Chicago’s founder. Until that time, it was John Kinzie who had been so recognized, a story that overshadowed the true tale.

Women were represented differently in the two fairs. The World’s Fair Bill passed by Congress in 1890 mandated a Board of Lady Managers. Led by Bertha Palmer, the board wielded much power and influence. The Women’s Building, designed by architect Sophia Hayden, exhibited works by women from many fields, including the arts, sciences, and home economics. Women, not only from America, but from other countries and cultures were featured. The Board also advocated for women’s rights and the vote. Women played lesser role in the 1933 fair. There was no parallel structure to the Board of Lady Managers, no Women’s Building. By then, women already had the vote, and while they participated in the fair, it was without the fervor and pioneering spirit that Bertha Palmer had led in the previous century.

Both fairs featured a day set aside for African Americans. The 1893 day was Colored People’s Day, established only after Ida B. Wells led protests of the fair’s exclusion of blacks in the exhibits, while being welcomed as paying customers. In 1933, National Negro Day also included a parade and a pageant in Solder Field with a performance of The Epic of a Race, “which portrays the Negro’s century of progress,” according to the Chicago Tribune. Behind the scenes, race relations were not perfect, but organizers of the 1933 fair did a much better job involving African Americans than their forefathers, offering policies that included black workers.

The lasting link between the two fairs is, of course, the one building that straddles the two eras. The building where the Museum of Science and Industry is now located began its life as the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 fair. It was not burned down, as were other buildings from that fair; it had a brick base underneath its staff cladding. The brick had been required by those lenders who insisted on fire protection for the priceless works of art they were sending to Chicago.

In the period between the two fairs, the building was called the Columbian Museum, created to hold the collections left over from the fair, with an emphasis on natural history. This became the basis of the collection for the new Field Museum of Natural History when it opened in 1921. The Columbian Museum was transformed into what we know today – a museum highlighting science and industry. That “working” coal mine from the 1933 fair landed there after the fair closed. The museum opened the in 1933, completing the link between the two fairs.

The other physical property left is Northerly Island, used as an integral part of the 1933 fair land mass. It later was offered to the United Nations for its headquarters, but was turned down. Following a period of use as an airport (Meigs Field), the island today is a music venue and park-like environment.

As we look back, each fair spoke of the future, lauded the city of its day, and promised better in the future. We remember them both with red stars on the flag.

Very nice article, Ellen. Thanks for sharing it. The L, of course, was already in existence when the Columbian Expo was held, but it was steam-powered. It converted to electricity in 1898, using the example of the Fair’s electric railway loop as a prototype. The original South Side Elevated Alley Railroad took people from the Congress Street station to the Fair in about 30 minutes.

Thank you. A wonderfully complete summary.

Really interesting article, Ellen. The subject of the World’s Fairs never gets old. Thanks for your scholarship and engaging style of writing!

Great article comparing the 2 fairs!

Terrific! Thanks for sharing the fruits of your research to help us enrich our tours.

Excellent article, Ellen. Interesting to compare and contrast the two fairs.

Thanks, Ellen for keeping us well informed! 🙂 Ronnie Jo Sokol

Thanks so much for your work on this fine article. I’m saving it.