By Maurice Champagne, Class of 2004

Of his six “principal elements”, Burnham listed “The improvement of the Lake front” as the first one, suggesting its importance to the Plan of Chicago.

Burnham advocated for the shore of Lake Michigan to be “treated as park space…. The Lake front by right belongs to the people.” (1) We owe the development of the lake front and the forest preserves to Burnham’s advocacy in his Plan of Chicago.

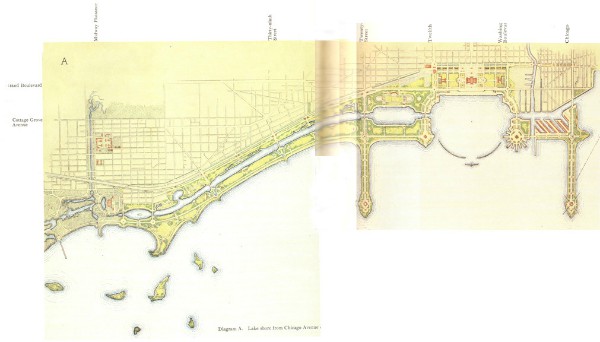

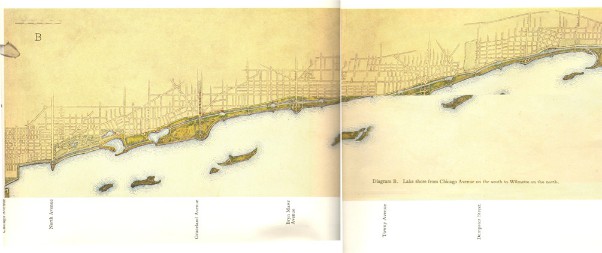

Diagrams A and B on Plate L show Burnham’s ideas for the development of the lake front and the barely discernable roads running alongside the parks along the lake.

Realization: The northern expansion of Lincoln Park and the development of Grant Park, Burnham Park, and Lake Shore Drive were completed roughly at the same time, between 1910 and 1934.

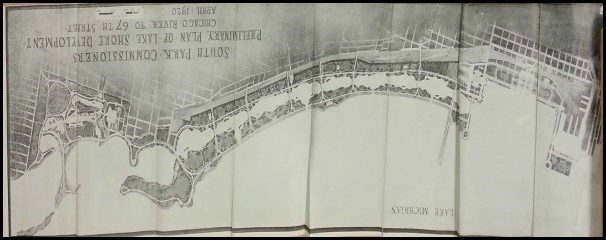

In 1911, the South Parks Commission acquired the riparian rights (the legal right to the land under water along the shoreline) from the Illinois Central Rail Road. (2) Delayed by lawsuits, Lake Shore Drive (called Leif Eriksen Drive from 1927-1946) was completed from the Chicago River to 57th Street by 1932. Leif Ericksen Drive south of 12th Street and the lake front park land were developed with landfill at the same time. (3) The landfill east of the Illinois Central tracks created the open lake front that Burnham envisioned, including an open roadway east of the IC tracks. (4) In October of 2013, a 2-mile extension of LSD was opened from 79th to 92nd Street. (5)

Based on the 1909 Plan of Chicago, this 1920 South Park Commission rendering (above), shows a roadway from Randolph to Jackson Park. It is from South Documents Box 1, Chicago Park District archives.

North LSD was begun by Gold Coast landowners in the 1880s and 1890s and further expanded in 1910, along with additional landfill for the expansion of Lincoln Park. “[T]he inner shore should be planted space. There should be lagoons, narrow and winding, along the north shore, and wider, with more regular lines, along the south shore.” (6)

Lincoln Park from Diversey to Foster, later to Montrose, was created before LSD was extended to Hollywood. Burnham suggested that nearly all of LSD be done using landfill, and that’s how the LSD we use today was created. Starting in 1910, LSD was extended from Ohio Street to Belmont Avenue. In 1925-1934, the city extended it further north, to Foster Avenue. The LSD Bridge over the river to connect the south and north parts of LSD was a Works Projects Administration (WPA) project completed in 1937. (7) The 1950s landfill used from Foster to Hollywood came from the building of Chicago’s expressways. (8)

At the same time (1924 to 1934) Lincoln Park added 300 acres with landfill from Belmont first to Foster, then to Montrose. (9) In 1934, the newly-formed Chicago Park District started the expansion of Lincoln Park from Foster to Montrose with WPA funds (10), including Montrose Harbor.

With underpasses on north LSD, overpasses downtown over the IC tracks, and overpasses and bridges over the IC tracks south of Roosevelt, we now have 28 miles of open and publicly accessible lake front. (11) It seems likely that Burnham envisioned a local street to separate the lake front parks from the residential area, but certainly not an eight-lane highway. But with park land along Lake Michigan, Burnham’s first goal was realized.

Burnham writes, “Imagine this supremely beautiful parkway, with its frequent stretches of fields, playgrounds, avenues and groves, extending along the shore in closest touch with the life of the city throughout the whole water front.” (12)

We don’t have to imagine it; we can see it any time we go the shores of Lake Michigan.

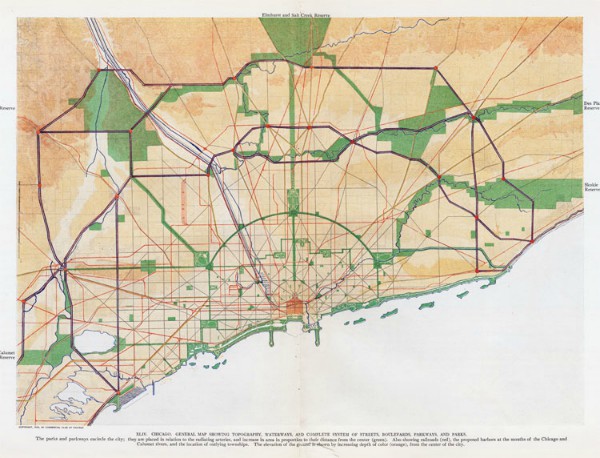

Burnham’s planning for expanding Chicago’s parks was regional. Another of his six goals was, “The acquisition of an outer park system and of parkway circuits.”

Burnham was not referring to the Jackson, Washington, Douglas, Garfield, Humboldt, nor Lincoln parks and their boulevards which had been developed in the 1870s, though he includes them in various diagrams.

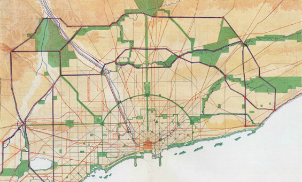

Rather, this goal relates to the development of the Cook County Forest Preserve and roads along the Des Plaines River. Burnham was aware of the 1899 Special Park Commission headed by Dwight Perkins as well as the 1903 Outer Belt Commission. He writes about the Commission’s ideas for the development of small parks. (13) In the Plan of Chicago, Burnham advocates for new parks and forest preserves. Plate XLIV lays out the plans for the outlying forest preserves from Lake Calumet Reserve to Elmhurst and from the Salt Creek Preserve to the Des Plaines River Preserve and the Skokie Valley Preserve.

Realization: The Illinois legislature authorized the creation of the Cook County Forest Preserves in 1913 to “restore and manage native habitats to maintain plant and animal diversity and ecological health.” (14) Some argue that the Special Parks Commission headed by Dwight Perkins, rather than Burnham’s Plan, deserves credit for the creation of the Cook Count Forest Preserve. Others acknowledge the influence of the Plan of Chicago. “The creation of the preserve district in 1914 meant that the Burnham Plan’s goal of making nature accessible to the public was well on its way to being realized.” (15) Though initiated by the Special Parks Commission and the Outer Belt Commission, Burnham incorporated the development of the forest preserves and advocated for its creation in the Plan.

For parkways along the Des Plaines River, Burnham wrote, “The Des Plaines River from the county line to Riverside flows mainly through thickly wooded country which the parkway plans include…” (16) One might argue that Milwaukee Avenue, River Road, Thatcher Avenue, Route 171, and Des Plaines Avenue along the Des Plaines River from Route 60 just east of Vernon Hills on the north to Route 34 just west of Lyons on the south are the parkways along the Des Plaines River, though not “parkway circuits.”

The Cook County Forest Preserve owes its existence to the Special Parks Commission and the Outer Belt Commission as well as advocacy in the Plan of Chicago. We must acknowledge the forest preserves, an outer park system, as another of Burnham’s goals that was achieved.

Please CLICK HERE to read Part 1 of The Realization of the 1909 Plan of Chicago.

References:

[1] Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago, Commercial Club of Chicago, 2008, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1993, p. 50.

[1] Theodore Kepner Long, Report to the Mayor and the City Council of the City of Chicago, Lake Shore Reclamation Commission, p. 316.

[1] “LINK OPENING GIVES 9-MILE NO-STOP DRIVE,” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963) archives, 18 Dec. 1929, p. 36.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 50.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 50.

[1] http://www.northlakeshoredrive.org/about_history.html

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Shore_Drive

[1] http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/300065.html

[1] https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/montrose-beach/

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Shore_Drive

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 51.

[1] Plan of Chicago, p. 44.

[1] https://www.cookcountyil.gov/agency/forest-preserves

[1] https://findingaids.library.uic.edu/exhibits/fpdcc/Foundations/Seeds%20of%20Preservation/seedsofpreservation.html

[1] Plan of Chicago, p.55.

Thanks, Maurice. Well-researched and well-written, as usual.

Maurice,

An interesting look at this issue, from the perspective of today looking back at what was achieved. Thanks for that and for the excellent research, as David says, as usual.