By Bob Michaelson, Class of 2011

The new headquarters of CAC is very near the Du Sable Bridge and across the river from the site of the homestead of Chicago’s founder. But while this is helpful in explaining the early history of Chicago to tourists, it also raises some puzzling questions that we should be prepared to discuss with our visitors.

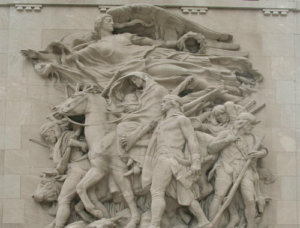

For example, the northwest bridge house of the Du Sable Bridge has a sculpture by James Earle Fraser titled “The Pioneers.” Who could have been more of a Chicago pioneer than Du Sable? Yet look at the sculpture, and read the plaque:

“”The Pioneers – John Kinzie, fur trader, settled near this spot in the early years of the nineteenth century. One of a band of courageous pioneers – who with their lives at stake – struggled through the wilderness, breaking soil for the seeds of a future civilization. Presented to the City by William Wrigley Jr. – 1928.”

No image of Du Sable, and no mention of him on the plaque. How did this happen?

Apart from the racism in Chicago – this was just nine years after the bloody 1919 race riot – Chicago had largely forgotten Du Sable, and not just by chance: the family of John Kinzie worked to present a version of the city’s history that significantly diverged from the facts.

For a factual account, CLICK HERE to read Early Chicago, the excellent and highly detailed account of our early history. From that, and other sources, we learn that Du Sable, the founder of modern Chicago, was descended from Haitian and French ancestors—it is unknown where he was born. He moved from Detroit to settle in Chicago, possibly by December 1782. He established a prosperous farm here, though in 1800 he moved to what is now St. Charles, Missouri, selling his property to the French trader Jean Lalime. Lalime, in turn, sold it in 1804 to the newly-arrived John Kinzie. An interesting sidelight is that on June 17, 1812, Lalime was murdered by Kinzie – also not far from CAC’s site – the first murder in Chicago! CLICK HERE for a fascinating account of that incident.

Although there is a brief mention of Du Sable in A. T. Andreas’s History of Chicago: From the earliest period to the present time (1884) (CLICK HERE to read) – for many years the most that Chicagoans knew of Du Sable and Kinzie was what they read in the highly popular book by John Kinzie’s daughter-in-law, Juliette Kinzie: Wau-bun: the “early day” in the North-west (1856, with many later editions). Juliette never met her father-in-law, who died two years before she married his son; her account of his life was based on what she was told by her mother-in-law and other relatives.

In the 1932 Lakeside Press edition of Wau-bun, editor Milo Milton Quaife remarks in his introduction, “To the present writer it seems clear that Mrs. Kinzie had but the vaguest comprehension of the historian’s calling, and that in appraising Wau-Bun the reader should regard her as a literary artist, whose primary ambition was to produce an entertaining narrative. … For Chicago readers, her book has a particular significance not shared by those who are alien to the Windy City. So thoroughly has her narrative of the Kinzie family and of the massacre permeated the local mind, that not all the efforts of all the historians, probably, will ever succeed in replacing it with a more correct and judicial concept. Through her literary exploit, John Kinzie has become the Captain John Smith of Chicago history.”

This, then, was the distorted history of early Chicago reflected in “The Pioneers.” Fortunately, Quaife’s prediction of the futility of trying to convey the facts to Chicagoans has proven to be mistaken, in part through Quaife’s own efforts.

Perry Duis, in his Introduction to the 2001 edition (University of Illinois Press) of Quaife’s 1913 book Chicago and the Old Northwest: 1673 – 1835, says “one of the books’s most significant contributions [is] the recognition of Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable … as the first permanent resident of what would become the city of Chicago. Most Chicagoans had grown to believe the oft-repeated myth that installed the family of John Kinzie in that role. … Some later historians, including A. T. Andreas, had mentioned Du Sable but had provided little detail about his life. … Quaife … seized every opportunity to correct the story of Chicago’s birth. One came in 1933, when the University of Chicago Press published his Checagou: From Indian Wigwam to Modern City, 1673-1835, a brief and popular, yet insightful, account of the early city produced for the Century of Progress Exposition. Quaife included a sophisticated interpretation of Du Sable’s importance, Thus, Century of Progress visitors who bought the book read the true story .. ”

The other significant contribution to the recognition of Du Sable’s true place in Chicago’s history was the efforts of the African American community, in the form of the National De Saible Memorial Society, which worked tirelessly for years to have Du Sable recognized at the Century of Progress Exposition. For a full account, see Christopher R. Reed’s, “In the Shadow of Fort Dearborn: Honoring De Saible at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933- 1934.” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Jun., 1991), pp. 398-413. A more readily available account is found in Cheryl R. Ganz, The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: A Century of Progress (University of Illinois Press, 2008), Chapter 6).

By now the attentive reader will have noticed the variant spellings: “Du Sable,” “De Saible,” and others. As Early Chicago notes, “All of the surviving documents created in his lifetime give his surname as Point de Sable or Point Sable; he was only misnamed Du Sable long after his death.” Where did “Du Sable” come from and how did it become the standard form of his name?

The National De Saible Memorial Society used a more historically correct spelling, and that is also the spelling that was used at the Century of Progress Exposition. However, as Cheryl Ganz explains in her book The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, page 184, footnote 2, : “In 1936, the renaming of New Wendell Phillips High School to Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable High School established the spelling followed today.” And on page 121 we learn: “In 1936, the clubwomen [of the National De Saible Memorial Society] campaigned for the renaming of New Wendell Phillips High School as Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable High School, a success that led to the spelling of ‘Du Sable’ still used today.

When Assistant Principal Annabel C. Prescott heard the suggestion to name the school De Saible High School, she protested. She feared that the students would be called ‘disabled.’’ Shocking though it is, it seems that the name of the school was made “Du Sable” as protection against an all-too-likely slur calling the students “disabled.” Thus “Du Sable,” selected by Chicago’s African-American community, became the standard form of the name for Du Sable High School, the Du Sable Museum, the Du Sable Bridge, and other public institutions.

A fascinating history; thanks for researching and sharing this!

Well done, Bob. I’m a big fan of getting back to the facts and dispelling myths. You’ve done that. Thanks.

Thanks, Bob. As usual, excellent scholarship and this is a fascinating story of the city’s origin. This is why we are all docents — to search out and find the truth about the development of Chicago. Thanks, again.

This is terrific! One more example of how being a docent means never-ending learning. Thank you!

Excellent article, Bob! Glad you detailed that DuSable did not see to Kinze but to Lalime who sold to Kinzie.. Maybe another article on Kenzie’s killing of Lalime and how he got off?