By Lorie Westerman, Class of 2006

Recalling the controversy of the early 1970’s, “the opponents of the Illinois Center wanted things to stay the way they were and what were they? Weeds, rats, warehouses, tracks, freight engines and boxcars and zero for the City”

William Johnson, chairman of IC Industries, parent of the former Illinois Central Railway, 1986

History of the Site

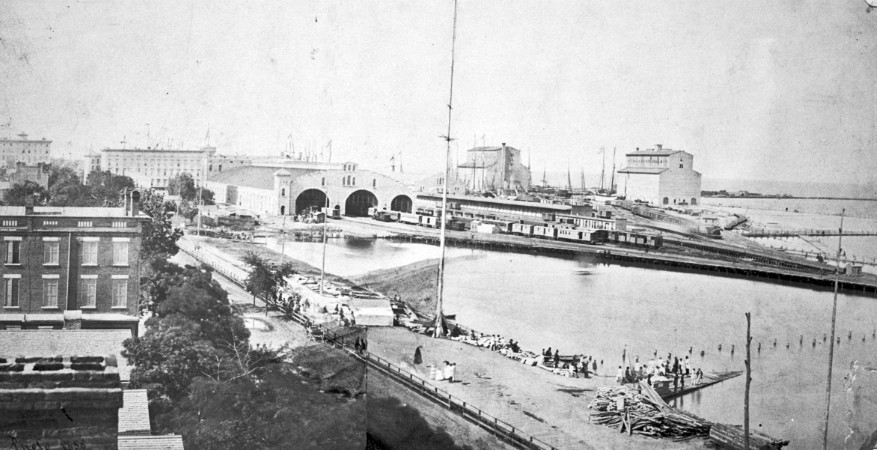

The history of the site began 165 years ago when the Illinois Central Railroad solved its dilemma of gaining access to the central city. The solution was to build a trestle on wood pilings that paralleled Michigan Avenue to a terminus at the south bank of the Chicago River. A freight yard, shop docks, warehouses, and grain elevators were constructed there. 1

By the 1920s the site had become too valuable to remain an industrial zone, and the railroad began making plans to build office skyscrapers above its tracks. The Depression intervened, and it wasn’t until 1955 that the first office skyscraper on Illinois Central land (the Prudential Building) opened. When William Johnson (Chairman of IC Industries) arrived in Chicago in 1966, he found that his predecessors at the railroad had already sold three options to the downtown land in 1962. 1

Why did the Illinois Central no longer need its freight lines? Automobiles and trucks were becoming preferred modes of transportation and commerce and industry were shifting away from the lakefront. By the end of WWII, everything that had been transported by boat was either on a carload rail or a piggyback rail car; a truck riding on a rail car made transfers easier. 2 The freight railyards were active until the mid-1970s and the Illinois Central’s commuter service remained until it was sold to Metra in 1987. The Metra Electric Line still terminates at the South Water Street Station on the lowest level of the Michigan Plaza North building.

The Development and the Challenges

The three developers who purchased land options and formed a joint venture in 1969 also appointed the Illinois Central as their agent in City negotiations. They were:

- Metropolitan Structures – owned land along the river where Illinois Center One (111 E Wacker Dr.), Two (233 N Michigan Ave.), and Three (303 E Wacker Dr.) office buildings, Columbus Plaza, the Swisshotel, and the Fairmont and Hyatt Hotels are located today.

- Illinois Central Corp. owned by Illinois Central Industries – held land in the center of the development where Michigan Plaza North and South (originally named “Boulevard Towers” at 225/205 Michigan Ave.) are located, as well as the vacant lot at Lake and Stetson that was to have been Boulevard Tower East and later the Mandarin Hotel.

- Interstate Investments, Inc. a subsidiary of Jupiter Industries Inc.–had options on the land for the entire tip of the tract along Lake Shore Drive (the S Curve still existed). Through another transaction with the railroad that had already been completed, they had constructed the Outer Drive East apartments (now 400 E Randolph) in 1963. They sold their interests to the other two investors in 1972.

Metropolitan Structures and IC Corp. focused their portion of the development primarily on commercial buildings and hotels and Interstate Investments (Jupiter) had focused on the residential component.

The plan for the site, composed virtually all on landfill over the air rights of the Illinois Central Railway and officially named the “Illinois Central Air Rights Development”, may have initially been designed by The Office of Mies van der Rohe in 1967. The city designated it as a Planned Development (PD) site, one of the first in Chicago. The firms SOM and CF Murphy designed an “unofficial site plan”, completed in 1966, as the first step in the negotiations with the developers. The project was to be completed in stages over 15 years; the PD allowed developers to obtain zoning for multiple buildings without obtaining zoning approval for each one. However, they still needed individual building permits to proceed. The developers could change the mix of buildings between commercial and residential as the market changed. The plan received the final approval of the City Council on September 17,1969, and incorporated some of the guidelines from a Department of Development and Planning document produced in May 1968.

The development was approved for a total of 83 acres – 51.44 acres for buildings and plazas, 6 acres for a park, and 3.86 acres for an “esplanade” along the River. The remaining acreage was designated for streets and public ways. The boundaries of the Illinois Center Development approved by City Council were the Chicago River on the north including the portion extending out into the River that is today’s east Riverwalk; Randolph Street on the south; Lake Shore Drive on the east; and Michigan Avenue on the West. 3

Why would the City approve such a large Planned Development?

In the 1970s, more people lived in the suburbs than in the city, and the tax base was eroding. The development of the mostly abandoned and unsightly 83 acre parcel was estimated to generate up to $86 million in additional tax revenue, 700 new construction jobs, and bring more people downtown to work and, hopefully, to live. The developers estimated that Illinois Center would include housing for 35,000 and office space for 45,000, a total population about equal to Evanston at the time. 4

What the developers proposed and how the critics responded

The developers promised a “futuristic city within a city” that included amenities to allow tenants and residents to “Work, Live and Play”:

• A public school

• A 6-acre park

• A music bowl

• Plazas with fountains, sculptures and a warm human atmosphere with organ grinders, flower carts and peddlers

• Swimming pools and health clubs

• Movie theaters

• Possibly a cultural center or maybe even a legitimate theater

Most of the amenities didn’t materialize, and the Center was criticized for its narrow, dark plazas and lack of green space. It was also faulted for its density, to which the developers answered, “this ain’t the suburbs! It’s a downtown complex, and it reflects that.” 5 In a Chicago Daily News article, the author called the proposed density of the apartments a “High Rise Calcutta” and noted the density was twice that of the CHA Robert Taylor Homes. While the original plan called for more residential space, the developers quickly determined there was a greater demand for more office and hotel space.

What it cost and who paid for it

While technically an air rights purchase, the actual sale was land. The developers bought the property in 1969 for a base price of $83,625,000 plus escalation ($100M total) during the 15-year development period after purchasing the options in 1962. By the time construction stopped in the 1990’s, the total cost of the project reached $3.5 billion.

Before construction could begin, street, sewer and water systems within the development, estimated at $48M – $60M, had to be constructed; they were paid for by the developers – an example is South Water Street. The city estimated spending $60M – $70M for other public improvements using City of Chicago, Chicago Park District, Federal government, State of Illinois, and Cook County funds. The northern extension of Columbus Drive, including constructing a bridge across the Chicago River, relocating Lake Shore Drive and eliminating the S-curve, the extension of Wacker Drive east to Lake Shore Drive from Columbus, and construction of a new fire station were to be paid for by the City. 6 The initial 300 feet of the extension of Wacker Drive east of Michigan Avenue (almost to Stetson) and the seawall along the River were paid for by Metropolitan Structures as part of the construction of the 111 E Wacker building.

The Architecture

Most of the buildings are designed in the mid-century, modernist style. While Mies had died by the time the plan was realized, his influence is evident in the design elements since Joseph Fujikawa, a Mies’ associate since 1945, and his firm took over as coordinating architects for Illinois Center.

The commercial buildings have a reinforced concrete frame and are clad in aluminum ranging in color from the bronze of Three Illinois Center (303 E Wacker Drive) to the dark gray or black of One and Two Illinois Center (111 E Wacker and 233 Michigan Avenue respectively) and the Michigan Plaza buildings (205/225 Michigan Avenue). The Fairmont and Hyatt hotels were clad in brick to give them “a personal, human feeling while the glass and steel buildings are stark in keeping with their commercial/business nature”.

The decision to use reinforced concrete for the core of the buildings was in part a financial one. Architect Dirk Lohan noted that, “when you pour a concrete structure, you get both a ceiling and a floor and don’t have to build them like you do with the use of steel.”

So what happened?

A commercial success initially, the Illinois Center continued to expand from its inception and was expected to finish in the late 1990s. But construction slowed and then almost stopped as the demand for modernist, “Miesian boxes”, declined. 7 Development stopped with five office buildings, five residential buildings mostly along Randolph and Harbor Drive, three hotels, an athletic club, and a fire station.

The remaining land was converted to the 9-hole Metro Golf at Illinois Center designed by Pete Dye. It opened in August,1994 and closed in 2001.

Part II of The Illinois Center Story will post on The Bridge on January 12, 2018.

Sources:

- “Illinois Center rose above the fray, kept growing”, Chicago Tribune, 12/22/1986

- “What if 60 years ago a new downtown had risen on Illinois Center site?” Chicago Tribune, 8/7/1988

- Council Proceedings, 9/17/1969

- “Sky City”, Chicago Daily News, 5/24/1968

- “Illinois Center towers become a city within a city”, Chicago Tribune, 4/24/1980

- “Illinois Center Rose above the Fray”, Chicago Tribune, 12/22/1986

- AIA Guide to Chicago, 2014

Fantastic info. Thanks

Thanks, Lorie. Good article and very helpful re the background of this still emerging development.

Love the picture of the rail yards in 1858. I have read about the trestle in the lake but have never seen a picture of it. Tom

Another key reason that the freight lines were no longer needed near the Chicago River was the move of the port of Chicago to Calumet beginning in the 1920’s. Pris

Thanks for your work on this, Lori. Great information.