By Bill Coffin, Class of 2004

Tour Director, Art Deco Skyscrapers: Downtown and Art Deco Skyscrapers: Riverfront

How did the Chicago Board of Trade Building come to be located at the south end of LaSalle Street?

By 1880, the Board had outgrown its headquarters in the Chamber of Commerce Building on the southeast corner of LaSalle and Washington. Board members groused that the trading floor was so crowded that messages could be delivered only by small boys crawling between adult legs. So, chaired by John Bensley, a committee was formed to find a site on which to build the Board a new, bigger building.

William Scott, of Erie, Pennsylvania, offered his property. It was bounded by Jackson and Van Buren on the north and south and by Pacific and Sherman on the east and west. But it was utterly unsuitable as the site of a large office building because it was split right down the middle by LaSalle Street (a condition created in 1868 when LaSalle was extended from Jackson one block south to the new passenger rail depot on Van Buren).

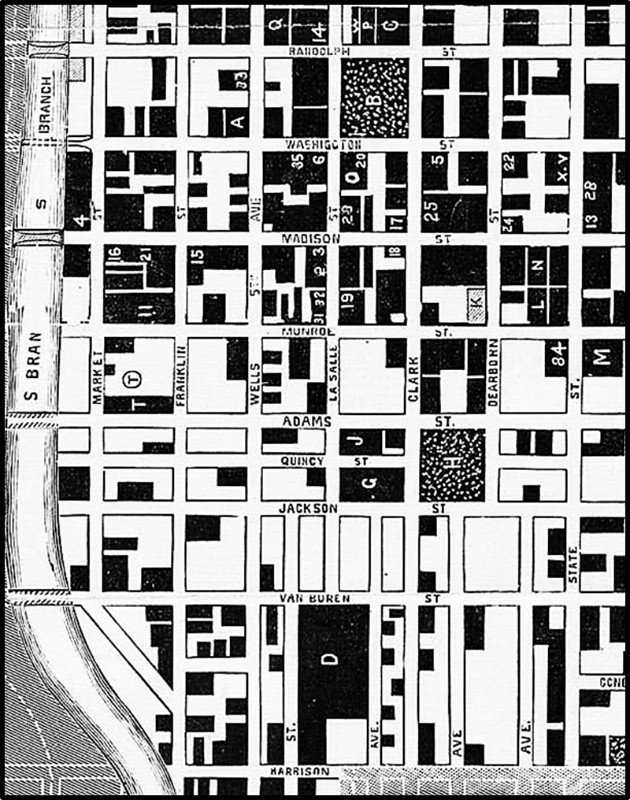

(On this map from 1872, at LaSalle and Washington, the Chamber of Commerce Building is “O” and the Union Building is “6”; at LaSalle and van Buren, the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Depot is “D”. “The New Chicago,” Chicagology)

To entice the Board to buy the property, Scott offered to ask the city to vacate the offending portion of LaSalle (and to widen Pacific and Sherman in exchange). If the property were no longer split by that troublesome street, a move there, just four blocks south, would keep the Board close to the banks in the financial district yet give it room to grow. So, the Board agreed in principle to Scott’s proposal.

On June 23, 1881, the Chicago City Council passed an ordinance vacating LaSalle south of Jackson. The ordinance was said to be for the good of the public, but the Board seemed to be the one true beneficiary. In a report to the mayor, the council wrote that, if the Board did not buy, and build on, the new site within two and a half years, LaSalle would be reopened.

Not everyone was happy about the prospect of the Board’s relocation. Some Board members expressed alarm that the Scott property was so close to what was called Biler Avenue – the stretch of Pacific near Harrison where prostitutes and their patrons snuggled and staggered, drunk as boiled, or biled, owls, as the saying went. And property owners near the Chamber of Commerce Building were fearful that the desirability, and value, of their property would plummet as tenants followed the Board and flocked south.

One of those fearful owners, the Union Building Association, sued the city, demanding that the vacation ordinance be declared void. Pending a decision on the merits, the court issued a temporary injunction prohibiting the city from taking any further action.

Then, under the cover of darkness on the night of July 9, LaSalle Street was sledge-hammered to bits. The next day, a reporter from the Chicago Daily Tribune surveyed the scene and encountered committee chairman Bensley who related the following tale. A couple of weeks earlier, opponents of the Board’s relocation had attempted to buy the property from Scott. As he had agreed to do should this situation arise, Scott tipped off Bensley who, with two other friends of the Board, promptly purchased the property. As Bensley explained, the city had handed the street over to Scott when it passed the vacation ordinance (and had complied with the court’s subsequent injunction, having not participated in the demolition). The new owners were then free to do what new owners do – redecorate!

In the end, the courts allowed the Board to keep the now demolished street. The Union Building Association’s case was dismissed by the Illinois Supreme Court. According to the court, a property owner can be compensated for the city’s obstruction of a public way only if he has suffered a special injury unlike that suffered by the general populace, but the Association could claim no such special injury.

Two other suits were filed by the civic-minded Hesing family. In his suit, Anton Hesing, the former Cook County Sheriff, insisted that the city council should not be allowed to donate a public street to a private enterprise, and he alleged that aldermen had been bribed to do so. Following the reasoning used against the Union Building Association, the Illinois Supreme Court dismissed the case.

Anton’s son, Washington Hesing, the future Chicago Postmaster, began a quo warranto proceeding, which challenges the authority of public officials and is brought in the name of the people by the Attorney General. The Attorney General at first agreed to participate in the proceeding, as is required, but later changed his mind. As a result, the Illinois Supreme Court dismissed this case, too.

In addition to the hints of bribery in Anton Hesing’s lawsuit, there were hints of bribery in the press. As the Tribune reported on July 22, 1881, a month after the ordinance had been passed, several aldermen gathered at a tavern where witnesses heard one alderman angrily demand to know the whereabouts of his bagman so he could collect his share of “the LaSalle Street money.” The other aldermen denied that there had been any bribery and blamed the outburst on four rounds of drink.

And recounting the events of the summer of 1881 in a letter to the Tribune, published on February 3, 1886, the former secretary of the Board of Trade revealed that “Bensley wanted the board to appropriate $10,000 … for costs in the vacation of the street. No one knew what was to be done with the money, and as the item `$10,000 for vacation of LaSalle Street’ would not look good on the records it was added to the purchase price … Shortly after this, the measure passed in the Council … As to what became of that $10,000, it is only to be supposed what disposition was made of it.”

The first Board of Trade Building was completed on the former Scott property in 1885 and was then replaced in 1930 by the second — an eye-catching Art Deco skyscraper, which still stops traffic today at the end of LaSalle Street.

Sources:

Sounds like history repeats itself in the middle of the night…..airport?

Bill, what a wonderful tale you tell. And I love not only your story but the word choices that make the piece come alive. Thanks, Ellen Shubart

Bill – I second Ellen’s praise of your article. And I hope that in Part II you’ll quote Montgomery Schuyler’s witty 1891 comments on the 1885 Board of Trade Building, most conveniently found in American Architecture and Other Writings, Harvard Univ. Press, 1961, pp. 253-254.

Bob Michaelson