by Tom Stelmack, Class of 2017

I was first introduced to Benjamin H. Marshall when I noticed a contractor restoring the very dilapidated Atlantic Bank Bldg. on Michigan Ave. The president of the company was my neighbor, and I decided to tap his good will to allow me to don a hard hat and enter the building during construction. Here are the links to the articles I published on the Bridge.

I was first introduced to Benjamin H. Marshall when I noticed a contractor restoring the very dilapidated Atlantic Bank Bldg. on Michigan Ave. The president of the company was my neighbor, and I decided to tap his good will to allow me to don a hard hat and enter the building during construction. Here are the links to the articles I published on the Bridge.

http://cacthebridge1966.com/hotel-julian-from-blight-to-beautiful/

http://cacthebridge1966.com/saint-julian-watches-over-millennium-mile/

While developing the Architecture of the Magnificent Mile tour with two other docents, I included Marshall’s Lakeshore Bank and Trust Bldg. at 605 N Michigan Ave. I soon realized that few people knew his name, and yet he had designed several now-landmarked buildings. In 2024, I created a bus tour to commemorate his architecture, coordinating with the Benjamin Marshall Society’s celebration of his 150th birthday (https://www.benjaminmarshallsociety.com). I was then hooked into honoring this forgotten Chicago architect. So, here is a brief narrative that chronicles his career. A video of his life presented by Lucien LaGrange, Bill Curtis, and others can be found: https://f.io/m2J3dLDj.

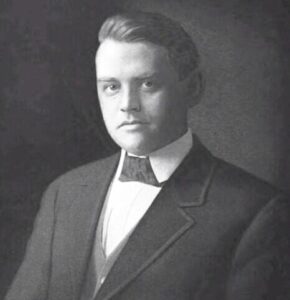

Marshall was born on May 5, 1874, into a wealthy family in the Hyde Park area. His mother was of French descent. While not a great student, he was creative and apprenticed as a clothier from 1890-2. He was later known for designing his own wardrobe, very Gilded Age in style. By 1893-4 he apprenticed with the architectural firm of Marble and Wilson. He designed homes for his father that exist today on S. Ellis Ave. Marshall was influenced by Daniel Burnham and the Columbian Exposition. While he was a classicist, he exercised creativity by melding several styles together. This was often contrary to the more common architecture of the time (Chicago School, Gothic revival etc.).

With the departure of Marble, he became a partner with Wilson (1895-1902), having been licensed in 1898. While he designed high-rise apartments during this period, he was known for designing theaters for the Powers Syndicated theatre group. He updated the Sullivan-Adler “Hooley Opera House” in 1898, then designed the Illinois Theatre in 1900.

By this time he was well established and had started his own firm by 1902. All of the theatres he designed were known for their French décor and also for safety and comfort. This became paradoxical, however, because of the ill-fated Iroquois Theatre. On December 30,,1903, a fire consumed the building and took 600 lives. He was exonerated in 1904, following an investigation that placed much of blame on the contractor. He then designed and built the Colonial Theatre in the same location, but it was demolished in 1925. The location is now the Rapp Brothers Nederlander Theatre.

In 1905 Marshall brought Charles Eli Fox into the firm as a partner. He was an MIT graduate and had been an employee of Holabird and Roche, essentially as a project manager. Their partnership flourished from 1905-1923, and they created 70 of the 121 structures Marshall designed. These included theatres in Kansas, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, New York, and the Blackstone in Chicago. In addition, there were apartments, offices, warehouses, homes, clubs, and a music venue at Ravinia Park.

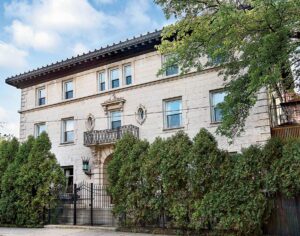

Landmarked structures include: South Shore Country Club, now Cultural Center; (1906, 1909, 1916; Mediterranean and Adamesque), Blackstone Theatre-Hotel (1910-1909 French Renaissance), Drake Hotel (1919 Italian Renaissance), and Edgewater Beach Hotel/Apartments (1924 Mediterranean). Unfortunately, their partnership dissolved acrimoniously c. 1924. Marshall continued as a solo practitioner until 1931, designing notably the Edgewater Beach annex, the Drake, and the 210 E. Walton Apartments, two banks in the Uptown area, JB Murphy Memorial (recently renovated), and a clubhouse for the Arlington Park Race Course. From 1931 until his retirement in 1938, he partnered with Walton and Kegley.

Marshall’s personal life was consistent with the Gilded Age, and he was considered by many to be Chicago’s Great Gatsby. His mansion and studio were located across the street from the Bahia Temple in Wilmette. His was a successful marriage, producing two daughters and a son. He entertained lavishly; British Royalty arrived by boat and docked along his shoreline. His parties were interesting. It was reported that showgirls frolicked in his swimming pool wearing dissolvable bathing suits. He enjoyed his affluence and owned expensive automobiles like Packard Bells, one of which he ‘hot-rodded’, and a Pierce Arrow “camper”.

The depression took its toll, and the property was sold to the Goldblatt family (department store fame) that also lost the property. Sadly, the donation to the Village of Wilmette was rejected, and the only remaining structure is the gate that led to the mansion.

I hope with this publication you’ll appreciate why I’m resurrecting the prominence of this remarkable Chicago architect.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Definitely one of Chicago’s most colorful architects! Thanks for all this interesting information.

Marcia

Thanks very much Tom! Enjoyed reading this.

Wonderful write-up, Tom. I was familiar with his name, but knew nothing about him. Thank you.

Interesting architect – thanks for the write up/pictures.

I have often admired 1550 North State Parkway from the southeast corner of Lincoln Park. Thanks for the information on its architect!

Thanks so much, Bob, for recognizing the work of Benjamin Marshall. We recently moved into our renovated unit in the Edgewater Beach Apartments (AKA the “Pink Building” — all that remains of the famous hotel and residential complex) located at N. Sheridan Rd. and Bryn Mawr Ave., and I can assure you that EVERYONE who lives here knows who Benjamin Marshall is! I’ve read that while Marshall was exonerated in the investigation of the tragic Iroquois Theatre fire, it weighed heavily upon his shoulders, prompting his commitment to “fire-proofing” every structure he designed thereafter. Our renovation was down to the studs, so we were privileged to see tough-as-battle-armor structural brick that lines the walls right up to the custom designed steel doorframes. You can imagine how my blood pressure spikes when I drill into the nearly century-old plaster to hang pictures, not knowing for sure if there’s an impenetrable layer less than an inch below the surface — sometimes the magic works and sometimes it doesn’t. This, however, is far less than a complaint than a terrific amusement (I’m learning how to manage the challenge). Living here is delightful, especially knowing the history behind the great building!

Today (Aug. 15), WGN ran a nice feature on Benjamin Marshall. The guest in the studio was Jane Lepauw from The Benjamin Marshall Society.

https://wgntv.com/morning-news/morning-news-guests/learning-more-about-iconic-chicago-architect-benjamin-marshall/