by Tim Thurlow, Class of 2015

Photos by the author

Today, nothing remains of Fort Dearborn except for metal markers implanted in the sidewalks around the intersection of Wacker Drive and Michigan Avenue and a bas relief of the fort below the sign of the London House. The markers on the northwest corner indicate where a block house once stood. On the Walk Through Time tour, guests find it hard to imagine a frontier fort in the middle of this busy intersection. But in 1803, the young United States government thought a fort at this spot was of vital importance; it could protect American interests in the fur trade, one of the most lucrative enterprises in the 18th and early 19th centuries. A post for fur trading near the mouth of the Chicago River had been established by Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable in the 1780s. John Kinzie acquired the property in 1800 and continued to trade furs at this spot. Kinzie was the most prominent of the early white settlers and is sometimes called the first “boss” of Chicago.The United States was in direct competition for furs with the British, who were operating out of Canada. The treaty that ended the Revolutionary War called for the British to turn over forts at Mackinac and Detroit. But it was an uneasy situation: the British were slow to relinquish the forts. They expected the American experiment in representative democracy would fail, and they would soon be back. Another reason to build a fort here was that with the acquisition of the Louisiana territory in 1803, American interests would lie increasingly in the West, with trade passing through the Chicago River and the Chicago portage.

The fort was to be named for Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War, Henry Dearborn, and the man chosen to design it was John Whistler, 48 years old at the time. Born in Ireland, he had been a British soldier during the Revolutionary War and fought at the battle of Saratoga. After the war, he returned to the United States as an immigrant and began a long career in the U.S. Army. When he died in 1826, he was the storekeeper of the Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis.

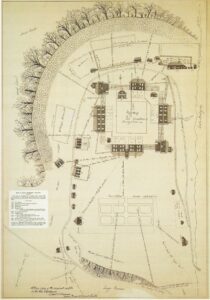

In the summer of 1803, Whistler arrived at the mouth of the Chicago River by schooner with his wife and several of his 15 children. His son William was a lieutenant in the army and took charge of some of the construction. Another young son, George Washington Whistler, grew up at Fort Dearborn, playing among the palings of the fort until he was ten years old. George went on to build railroads in the United States and Russia. He fathered James McNeil Whistler, often thought of as the finest American painter of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Below is a fine drawing of Fort Dearborn done by John Whistler. Perhaps artistic talent passed down from grandfather to grandson.

One aspect of life at a frontier fort was frequent interaction with Native Americans. At Fort Dearborn, the Potawatomi were regular visitors. The fort was located in Indian Country, a term used to describe large parts of what is today northern Illinois, northern Indiana, lower Michigan, and western Ohio. It was inhabited by many native tribes, including the Miami, the Sauk, Ojibwa, Odawa, Potawatomi, and others. These tribes enjoyed a flourishing trade network. They hunted in the forests, raised crops along the rivers, and trapped furs. White settlers were few and far between.

Finding provisions for Fort Dearborn was a constant challenge. The Whistlers raised crops and the 69 resident soldiers hunted for meat. John Whistler got into trouble when he was accused of co-mingling farming expenses with official funds. He also antagonized the irascible John Kinzie. As a result, he was recalled to Detroit in 1810. This may have saved his life and that of his family.

The United States declared war on Great Britain in June, 1812. Less than a month later, the British captured Fort Mackinac, making resupply and reinforcement of Fort Dearborn impossible. In Detroit General Hull ordered Captain Nathan Heald, the new commander of Fort Dearborn, (for whom Heald Square is named), to retreat to Fort Wayne. Heald set off with soldiers, women, and children on August 15, 1812. Within a short distance from the fort, the column was attacked by some 500 Potawatomi warriors. Only 28 soldiers survived. Heald and his wife were taken prisoner and later ransomed. The Potawatomi burned Fort Dearborn to the ground.

Two years later Fort Dearborn was rebuilt and continued in use up to the time of the Blackhawk War in 1832. After that, the fort fell into disuse. In 1837, the federal government deeded the fort and its reserve to Chicago, including that part of the land that became Grant Park and where the Chicago Cultural Center stands today. The fort was demolished in 1857.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

CLICK HERE for more stories on The Bridge.

Thanks so much for personalizing those brass strips in the sidewalk. The history is great and I’m sure your tourists love it when you integrate the information into your tours. Thanks

Insightful article, Tim. Thanks!

Thanks great story

Tim, what a great story and awesome inspiration to include it during WTT tour!

Thank you for this!!

Tim – This was a terrific summary and provided detail and context that helped bring this all to life. THANK YOU