By Maurice Champagne, Class of 2004

Daniel Burnham’s name is known far beyond the confines of Chicago. His city planning projects include Manila and Bagulo in the Philippines and others in Cleveland, San Francisco, and Washington D.C. Here in our city, his city, the Plan of Chicago has shaped many elements of our cityscape. His overarching goal was to design “a well-ordered, convenient, and unified city.” (1) Burnham states these six goals as the “principal elements” (2) of the Plan of Chicago:

“The development of centers of intellectual life and of civic administration, so related as to give coherence and unity to the city.”

“The improvement of the Lake front.”

“The acquisition of an outer park system and of parkway circuits.”

“The improvement of railway terminals, and the development of a complete traction system for freight and passengers.”

“The systematic arrangement of the streets and avenues within the city, in order to facilitate the movement to and from the business district.”

“The creation of a system of highways outside of the city.”

While we know about Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan, how much of it was actually implemented? Some docents say “little;” some say “50%”; some ignore the quantification altogether. Actually, many improvements advocated in the 1909 Plan came about after Burnham died in 1912. Consider these:

• Navy Pier (Municipal Pier) in 1916 and Calumet Harbor in 1921.

• Michigan Ave bridge in 1920.

• Development along a boulevard north of Michigan Ave from 1921 to 1929.

• Field Museum in 1920/1921, though not sited where he had envisioned.

• Old Post Office (1921, 1932) connected to the railroads.

• Consolidation of RR terminals with Chicago & North Western Terminal in 1911 and Union Station in 1925, though others continued in use into the 1970s.

• Creation of Northerly Island by 1925, the only one of many in the Plan.

• Electrified and sunken Illinois Central tracks by 1926.

• Double-decker EW Wacker Drive in 1926.

• 120 miles of street-widening, including Michigan (and Pine) from Washington to the Water Tower, Canal, Roosevelt, LaSalle, Ashland, and Western Avenues in the 1920s, and Congress in the 1950s.

• Lake Shore Drive extended from 14th to 57th streets between 1917 and 1932, then north to Belmont by 1929, then extended north to Foster in 1933, to Hollywood in the 1950s, and again south almost to the Indiana border in 2013.

• Yacht Harbors (the 10th opened in 2012) along 28 miles of open and accessible lake front, though we must credit A. Montgomery Ward for keeping Grant Park free of buildings.

These improvements are among the developments resulting from the Plan of Chicago. Carl Smith’s book The Plan of Chicago devotes Chapter 8: Implementation to naming many of these. The Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the Plan of Chicago provides another assessment of the implementation of aspects of the Plan.

In 2008, Chicago 2020 made an extensive review of the Plan in its The Plan of Chicago: A Regional Legacy. This 20-page booklet summarizes “What happened—and what didn’t—as a result of the Plan of Chicago” with text, photos, and graphics. While the booklet lists the six “principal elements” it does not examine each goal individually.

So—did the City of Chicago achieve Daniel Burnham’s six goals as listed in the 1909 Plan of Chicago?

In this series of articles, I propose to show how the goals Burnham laid out were realized, though not necessarily in the way he envisioned. Let’s start with this goal, the one most often viewed as a failure:

“The development of centers of intellectual life and of civic administration, so related

as to give coherence and unity to the city.”

In Chapter VII, “The Heart of Chicago,” Burnham argues that the Michigan Avenue expansion north of the river and his proposed civic center at Halsted and Congress are “the keystone of the arch” (3) of the Plan of Chicago.

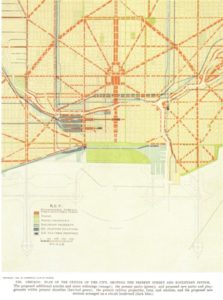

We can see what Burnham had in mind by viewing Plates CXXII, CXXIX, and the famous Jules Guerin painting (Plate CXXXII) as well as this CXI drawing (below left), with streets radiating out from the proposed civic center.

Burnham must have known that city hall would not be built at Halsted and Congress, as Holabird and Roche had been awarded the design contract in 1905. The city started the construction of the new City Hall/County Building downtown in 1909, on the same site as earlier city hall buildings had been constructed.

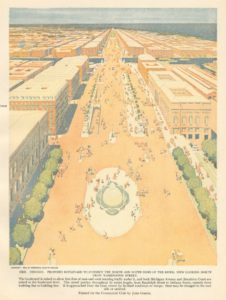

Plate CXI expresses Burnham’s idealized vision for this goal of giving “unity to the city.” His vision to re-center the life of the city around a new civic center at Halsted and Congress never materialized nor did the diagonal streets. This expansion of Michigan Avenue did not become Chicago’s Champs-Élysées (as suggested by another famous Guerin painting, Plate CXII, below right), though North Michigan Avenue did become the city’s social and commercial life north of the river. And in the 1920s and 1930s, this section of Michigan Avenue was called “Boul Mich.” (4)

In the “Heart of Chicago” he wrote: “The lake front will be opened to those who are now shut away from it by lack of adequate approaches; the great masses of people which daily converge in the now congested center will be able to come and go quickly without discomfort; the intellectual life of the city will be stimulated by institutions grouped in Grant Park; and the center of all the varied activities will rise the towering dome of the civic center.”

While no additional museums were built in Grant Park, we have a downtown lake front park extending from Randolph to Roosevelt that is open to everyone. South of the Chicago River, Michigan Avenue is known as the Cultural Mile. The Art Institute, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Museum of Broadcast Communications, and the Chicago Architecture Center are within a mile and a quarter of each other. Three other museums are on the Museum Campus, a little more than a mile from the center of downtown. City, state, and federal government buildings as well as court buildings are not consolidated into one civic center, but they are in close proximity to each other and in the center of the downtown.

Even without Burnham’s plan for a civic center at Halsted and Congress, Chicago achieved his goal of “The development of centers of intellectual life and of civic administration, so related as to give coherence and unity to the city.” (5)

Carl Smith reports, “Between 1912 and 1931, Chicagoans approved 86 Plan-related bond issues covering 17 different projects with a combined cost of $234 million.” (6)

In my opinion, the 1909 Plan of Chicago achieved all of Burnham’s six major goals as he lists them in Chapter VIII. In subsequent articles, I will examine each of the other five goals.

I wonder what Burnham would have thought about how some of them were achieved. He was aware that the Plan of Chicago would not be implemented exactly as he envisioned. He wrote: “Therefore, it is quite possible that when particular portions of the plan shall be taken up for execution, wider knowledge, longer experience, or a change in local conditions may suggest a better solution.” (7) Sadly, almost all that was accomplished happened after Daniel Burnham died.

References:

1 Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago, Commercial Club of Chicago, 2008, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1993, p. 4.

2 Plan of Chicago, p. 121.

3 Plan of Chicago, p. 117.

4 https://webapps.cityofchicago.org/landmarksweb/web/tourdetails.htm?touId=25

5 Plan of Chicago, p. 118

6 The Plan of Chicago: Remaking the American City, University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 133.

7 Plan of Chicago, p. 2.